From an aerial view between January and March, the Bediya chilli mandi (market) appears as a vast red blanket of chillies. Sundays bring crowds of traders & farmers, and the mandi is abuzz with life. Workers stuff chillies into large sacks placed on iron stands, pressing them down with their feet to make room for more. Four tin sheds stand in the center of the market, where farmers and traders negotiate their deals.

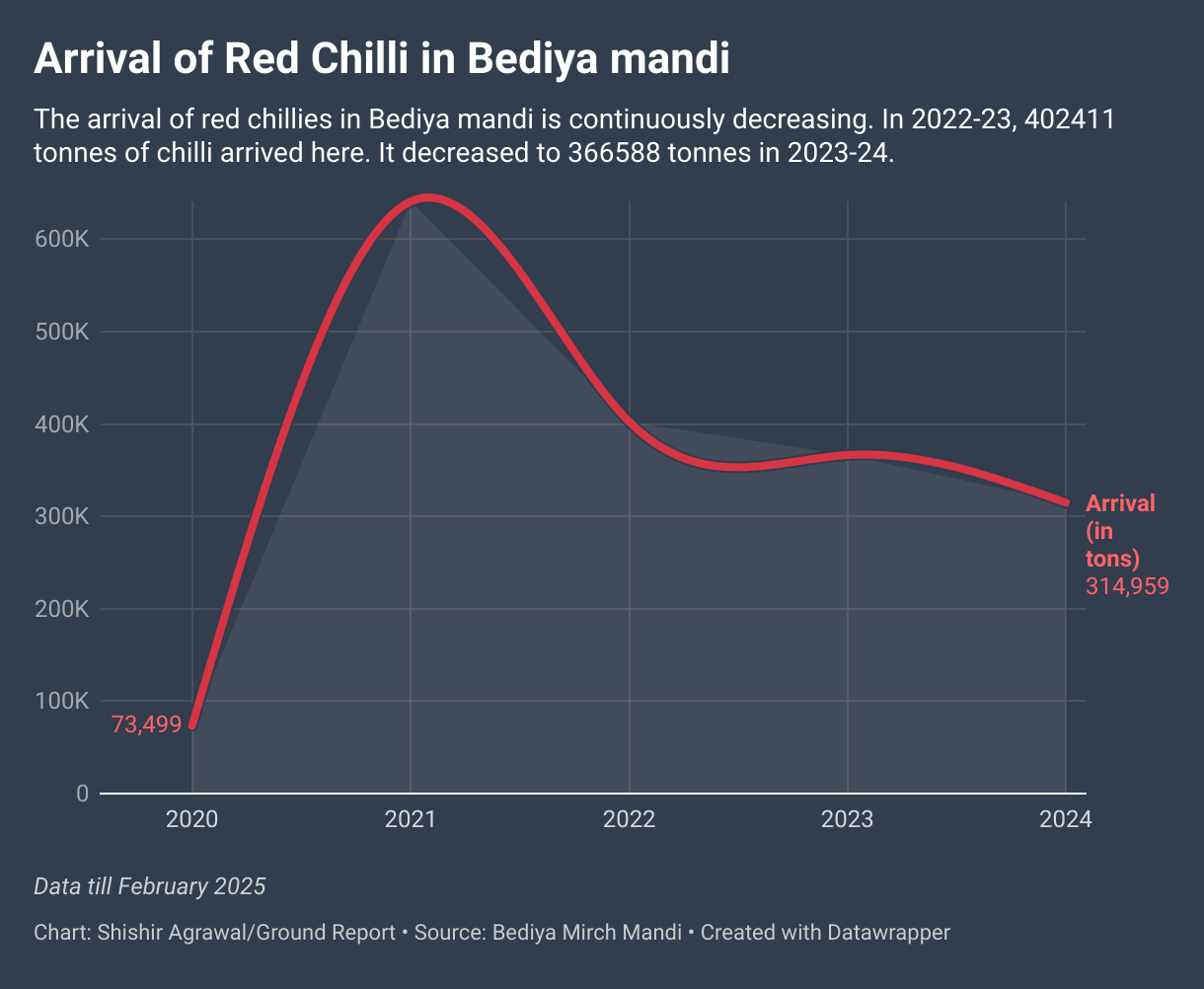

As March draws to a close, the market presents an unusual sight this year. The customary red expanse appears noticeably small. Traders lament the significantly reduced arrival of red chillies in the market. While farmers report that production has dropped by half compared to normal seasons.

Farmers attribute the low yield to irregular weather patterns and virus-borne diseases. As a result, many have shifted to selling green chillies instead of the traditional red ones that Khargone chilli cultivation is known for.

Red Chilli of Khargone

In order to understand the change in chilli production, it is important to understand why chilli is important. India is the largest producer, consumer and exporter of chili in the world. About 1.98 million tonnes of chilli is produced here. This is 43% of the total production of the world. Chilli is also the most exported (42%) spice in our country.

Andhra Pradesh is at the top in the country. According to the first estimate of 2023-24, 11,85,265 tonnes of chilli were produced here. The southern state is famous for its premium chilli varieties, including Teja, Byadgi, DD Best, 341, 273, and 334, which are highly sought after by exporters.

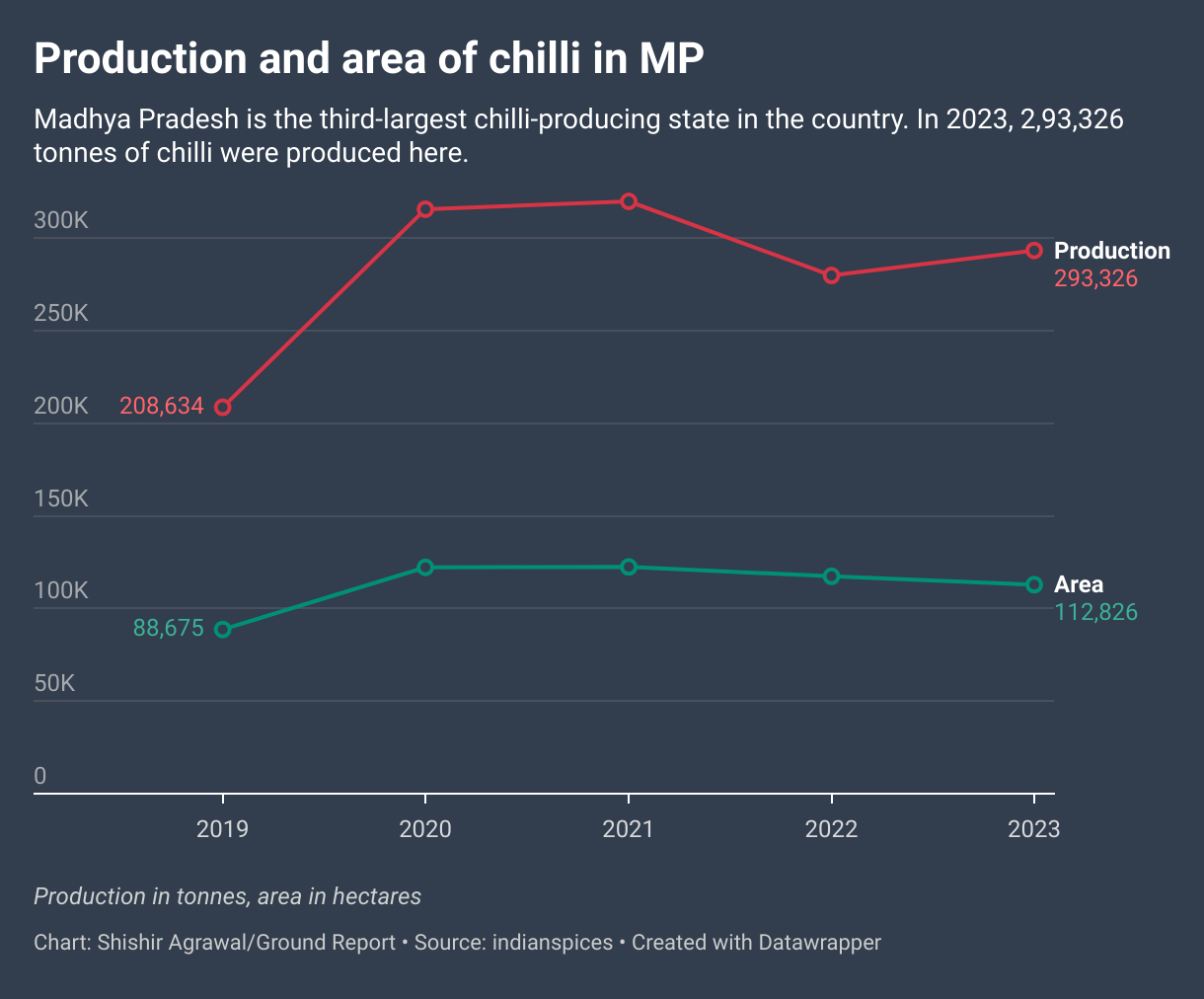

Madhya Pradesh is the third-largest chilli-producing state in the country. In 2023, 2,93,326 tonnes of chilli were produced here. Madhya Pradesh is known for its ‘Nimar chillies,’ grown in the Nimar region, and other varieties like ‘Mahi’ and ‘Mahi S-15,’ known for their medium to high heat and rich aroma.

In Khargone, farmers depend on Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) for all scientific information related to agriculture. Here, the responsibility of conveying this information to the farmers lies with Dr. RK Singh, Extension Scientist at KVK. Therefore, he keeps all the information related to agriculture in Khargone.

Talking to Ground Report, Dr Singh says that after cotton, chilli is the most important crop for the Nimar region. Here farmers are earning Rs 1 lakh to Rs 2.5 lakh from the production of one acre. He says that earlier chilli was cultivated in about 50,000 hectares in the district. But in 2024, its production was limited to only 45,000 hectares.

Farming is falling prey to diseases

Khargone farmers report that chilli cultivation areas have shrunk over recent years, directly impacting production levels. Vishnu Dogaya (29), from Kaldha village in Bhikangaon Tehsil, planted chillies across his 8-acre field.

He had prepared nurcery in his field in May to grow chilli plants from the seeds. In June, when the plants grew a little, he shifted them to main field. About a month after this, the crop started flowering. Everything was going well. But soon dark green spots started appearing on the leaves. Slowly, the leaves of the plants started withering. Dogaya noticed that the roots of the plant were turning black. These were the symptoms of collar rot in chilli.

In an effort to save his crop, Dogaya began using fungicides.

“We sprayed a combination of Carbendazim + Mancozeb, Tricyclazole, and Hexaconazole on the plants for 10 to 15 days, covering both the plant body and roots. Only after this treatment was the disease initially controlled,” he explains.

However, just a week later, his crop was attacked by fungus again, this time succumbing to wilt. Fusarium wilt, caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum, is the most dangerous disease affecting chillies. “The plant weakens and slowly dies,” he adds.

Explaining the severity of the situation, Dogaya says,

“When wilt strikes, the entire crop in the field is wiped out (died) in a single day.”

Unfortunately, Dogaya couldn’t save his crop from wilt this year, so he had no choice but to completely unroot his 8-acre chilli field and plant maize instead. This marks the second consecutive year that the 29-year-old farmer has faced losses from chilli cultivation. Reflecting on his previous season, he recalls,

“Last year, our crop was infested with black thrips. We initially managed to harvest 1-2 batches, but after that, the crop stopped growing altogether.”

Dogaya invested 7 to 8 lakhs in planting chilli in his 8 acre land. This does not include the cost of labour. Despite the huge expenditure, eventually, the red chilli he got could be sold for only 4.5 lakhs.

Farmers in Borut village, located about 6.5 km from Dogaya’s farm, share a similar story of crop failure. Devendra Patel, who cultivates chilli on 20 acres, has also been battling diseases in his field for the past two years. His crop has been infected by black thrips.

“No medicine works on a plant infected with black thrips. It causes 30-40% crop loss,” Patel shares.

Black thrips are 1-2 millimetre-sized insects. This insect was first found in a papaya farm in Bangalore in 2017. But in October 2021, it spread to chilli fields in 34 districts of 6 states including Andhra Pradesh, Telangana. A total of 5 districts including Khargone, Khandwa, and Dhar in Madhya Pradesh were also affected by it.

This insect sits on the chilli flower and sucks its sap. Due to this, the flower loses its nutrition, and it is unable to turn into fruit. This is the reason why Dogaya’s crop ‘stopped growing’ after the attack of this insect in 2023.

“Everything is happening upside down.”

Like other farmers, Bhagwan Ji Sejagaya from Borut has also been suffering losses in chilli cultivation for the past two years. He recalls that until two years ago, there was no need to sow another crop. The chilli planted in June would be harvested by March of the following year. “But now, the chillies are finished by December, so we have to plant gram or maize instead,” he says.

He blames this change to the rising prevalence of diseases affecting the chilli crop. When asked if he believes the changing weather could also be a factor, he acknowledges that the weather is indeed changing.

“When sunlight is needed, it is cold. When cold is needed, it rains. All this is happening upside down.”

Dr Singh of KVK says that to protect the chilli from the virus, it is important that there is a sufficient gap between rain and hot weather. If it rains continuously, the effect of insects increases, due to which the virus spreads from one plant to another. The farmers of Borut also repeat this. Devendra Patel says,

“As soon as there is moisture in the weather, black thrips start appearing in chilli. They do not come in summer.”

But as summer progresses, the groundwater level decreases rapidly. If there is no rain in early June, farmers have to depend on this groundwater for irrigation. According to Patel, chillies should get water for 5-6 hours in the first month, but in summer, the tube well does not run for more than half an hour.

Unsafe crop amid rising costs

Dogaya says that the labour cost of chilli farming is increasing every year. He says that earlier the rate of plucking chilli used to start from Rs 4 per kg and went up to Rs 6 per kg. But now the wages start from Rs 7. Whereas the wages for planting, spraying and weeding the crop used to be Rs 150 per day, but now it has reached Rs 250-300.

“Now, if you give Rs 200 to a labourer, he will work only till 2 o’clock. You will have to pay Rs 250-300 for the whole day.”

Similarly, he tells about the rising cost of pesticides and fertilizers; earlier, the cost of one acre was Rs 1 lakh, now it has become Rs 1.5 lakh. But there is no provision for the economic security of this crop amid rising costs. We asked many farmers including Devendra Patel what they expect to reduce the losses in chilli cultivation? Everyone gives more or less the same answer to this,

“The government should fix the rate.”

Actually, chilli is a vegetable and spice crop. The government does not give any minimum support price (MSP) to ensure its price. When a farmer takes his crop to the chilli market of Bediya, he sells his goods after negotiating with the trader. Patel says that last year, the rate of red chilli went up to 240 to 250; this time, the price stopped at 150 to 170. Whereas Dogaya believes that 15 to 17 lakh rupees should come out from an 8-acre farm. It is worth noting that according to the contingency plan of Khargone, 1011.71 kg of wet chilli is produced per acre here.

Whereas in the chilli market, this red chilli is dried and sold. Farmers say that after drying 4 kg of chilli, only 1 kg remains. Due to the continuously falling prices in the market and virus attacks, the farmer has started feeling insecure about selling red chilli. Talking to the farmers of Khargone, it is understood that they prefer to sell green chillies instead of waiting for the chillies to ripen and turn red.

Raghunath Chauhan of Naharkhodara village is a testimony to this change. He cultivates chillies in 1 acre. This year, he has earned a total of 1.5 lakh rupees from one acre. Out of this, he has earned 60 thousand by selling green chillies.

The effect of this trend among the farmers is visible in the arrival of Bediya Mirchi Mandi. The arrival of red chillies here is continuously decreasing. According to the data received from the chilli market, 402411 tonnes of chilli arrived here in 2022-23. It decreased to 366588 tonnes in 2023-24.

Red chilli is not just the identity of Bediya Chilli Market but of the entire Khargone district. To promote it, the state government proposed Khargone’s red chilli for a GI tag in 2023. Additionally, the government has included it in the ‘One District One Product‘ scheme for Khargone. However, for these efforts to succeed, it is crucial that Bediya and Khargone chillies stay in the public eye. In this context, the government must address the ongoing challenges of diseases through better scientific research, stabilize prices, and ensure the safety of farmers’ crops.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Fighting for breath: Khargone’s cotton workers battle Byssinosis

Can we talk about BT cotton, India’s only genetically modified crop

MP’s textile dreams face hurdles as ginning industry struggles

What is human cost of India’s pesticide consumption, and lack of regulations

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel