Trigger warning: This article discusses suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, please contact a mental health professional.

On 31st January 2025, there was utter chaos in the Sejla village of Khargone district of Madhya Pradesh. There is minimal transport in these areas; a private eight-seater vehicle called Toofan was hired to take Sanjay Chauhan’s brother, Dayaram, to the Khargone District Hospital 28 km from the village. For about 30 minutes, the situation in the vehicle was tense, with 40-year-old Dayaram battling his fate. He was declared dead at the hospital. The family later learned that he had consumed pesticides—toxic chemicals meant to kill pests in the agricultural fields.

The family recalled that he was Shiva Bhakt—a Hindu god known to consume ganja (cannabis) for intoxication. Dayaram would spend half of the month with the community of Shiva bhakts serving in the temples and would be found intoxicated, Sanjay, Dayaram’s brother, recalled. Sanjay repeatedly mentioned his brother’s drug addiction. Sanjay said, “He had nothing to worry about. He was completely free.”

Villagers call pesticides, or essentially any chemical, dawai—Hindi for medicine. Dayaram’s family is uncertain about how he got the pesticide and remains unaware of what might have led him to take such a step. Though, the easy availability of these pesticides has been linked to the disproportionate burden. Sometimes, a general store—a store with daily household items—will sell these toxic chemicals without any caution or verification. Apart from this, agricultural-related financial burdens from crop failures and debts drive some farmers to misuse these readily accessible chemicals.

In 1995, Professor Michael Eddleston, a clinical toxicologist at the University of Edinburgh, went to Sri Lanka to study snakebites but instead found a serious problem—pesticide poisoning. While observing patients in Anuradhapura Hospital, he witnessed an overwhelming number of self-poisoning cases involving highly toxic pesticides like monocrotophos and methamidophos (both organophosphate insecticides).

“Self-harm is often misunderstood. People don’t consume pesticides because they want to die; they do it to express distress,” Prof. Eddleston explains. “Unfortunately, highly toxic pesticides turn these moments of crisis into fatal acts. When a substance this dangerous is easily accessible, tragedies become inevitable.”

He is now the director of the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention in Edinburgh, Scotland.

In one corner of Khargone District Hospital, there was a small room. A dusty old tube light hung from the ceiling, casting a dim glow. The only window was shut. Two hospital beds stood against the wall, their sheets neat and untouched.

A police constable spent his day in the room, recording cases in an A4-sized register. He documented incidents that required police reports, mainly suicide attempts. Between January 24 and March 11, he had recorded 13 cases—all involving people who tried to end their lives by swallowing “medicine.”

He carefully wrote down the patients’ names, their fathers’ names, their caste, their village, and the police station under whose jurisdiction they fell. Most of them are from the tribal community. Only one belonged to the Dalit community, and one to the Rajput community.

“The ones who died were farmers,” he said calmly, still writing. “They can get these medicines (pesticides) easily.” His voice was steady, as if this were nothing unusual. He didn’t pause or look up, his head bent over the register, hands moving methodically. It was just another part of his routine.

Pesticide poisoning worsens in India

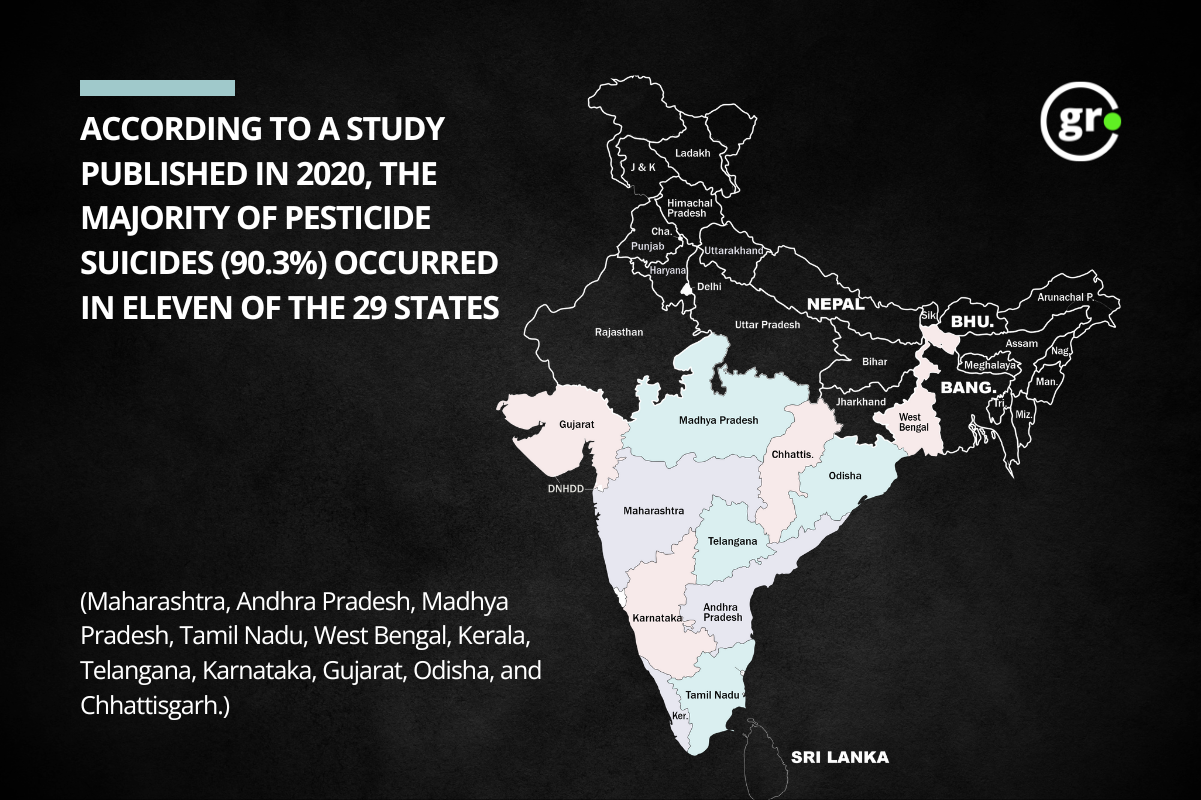

India’s pesticide consumption is relatively less, but pesticide poisoning is a big problem. In rural India, where more chemicals are used each year, the problem is even more serious. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data reveals the severity of the issue. From 2013 to 2022, the state of Madhya Pradesh reported 11,104 cases, contributing to a total of 60,968 across the country. The data shows a disturbing trend: in 2010 alone, there were 25,288 suicides linked to insecticides—a kind of pesticide—with 2,105 cases in Madhya Pradesh.

The study reveals that pesticide poisoning affected 65% of adults and 22% of children in India, and pesticides are the main cause of poisoning in India, responsible for two out of every three cases. A study looked at 134 research papers from 2010 to 2020, involving over 50,000 people. Pesticides, widely used in farming and homes, caused 63% of poisoning cases, according to the study.

During the soybean season (June to Nov), 42-year-old Nemichand and 38-year-old Dharmendra of Rolagaon in Ashta Tehsil, Madhya Pradesh, spray pesticides in 4-5 fields every day. Without any safety gear, they start at one corner of the field and walk in a straight line to the other, spraying pesticide on the plants to their right and left. In 2-3 hours, they cover one acre of crop on foot, earning Rs 250 (~3 USD) per acre. Nemichand said, “Spraying pesticide for a long time sometimes makes me feel dizzy. When I tie a cloth over my mouth, I have trouble breathing. But I earn 1000 rupees a day by working in three or four fields. That is why I do this work.”

Studies show even small amounts of a common insecticide called chlorpyrifos can make adults feel sick, cause blurry vision, and give them headaches. Eddleston highlights the long-term health impact on those regularly exposed to these chemicals. “Even those who don’t consume pesticides directly suffer. Farmers using them report nausea, dizziness, and chronic health problems. Pesticide drift contaminates water sources, exposing entire villages—including children and the elderly—to toxic residues.”

Nemichand said that when the wind direction suddenly changes, the pesticide goes into my eyes and nose. While Dharmendra has accustomed himself to the realities of his job and life.

India uses many hazardous pesticides

Dr. Donthi Narasimha Reddy, a visiting senior fellow at the Impact and Policy Research Institute in Delhi, agrees and emphasises that pesticide poisoning is not just an individual issue—it is a public health crisis. “We have seen entire villages suffering from mysterious illnesses—hair loss, neurological disorders, and even birth defects in newborns. Yet, in many cases, the exact cause is never officially determined,” he says. “If we cannot even diagnose what is killing people, can we call ourselves a scientific society? Instead of prioritising public health, the government is more focused on making it easier for companies to sell pesticides.”

Eddleston argued that regulations must be tightened. “The issue isn’t just that people misuse pesticides; it’s that lethal substances are allowed to circulate freely. We don’t leave sarin gas in homes—so why do we tolerate highly toxic pesticides being sold without strict controls?”

According to Pesticide Action Network (PAN) India, a non-profit group, India has 339 approved pesticides, and 118 of them are highly dangerous. Out of these, 81 are banned or restricted in many countries, and 68 are banned in more than 10 countries. Seven of these pesticides are also listed in global agreements for harmful chemicals. These dangerous pesticides make up 42% of all pesticides used in India. About 72% of the pesticides India brings from other countries are also highly hazardous. Nearly all (97%) of certain pesticides made in India are from these harmful chemicals.

Prof. Eddleston points to Sri Lanka’s success in reducing pesticide-related deaths through strict bans. “We have tried awareness campaigns and safe storage, but they don’t work. The only proven solution is to ban the deadliest pesticides. Where this has been done, suicide rates have dropped dramatically.”

On 11th March 2025, a day before we visited the Dayaram’s village, there was another reported case of pesticide poisoning. After his death, Dayaram’s wife continues to manage both farming and their two children, aged 17 and 15. Sanjay, who worked as a JCB operator, supports both families.

In our second part, we explored how pesticides are sold, what safety measures are in place, and the risks of accidental poisoning.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Why does India use fewer pesticides per hectare of cropland than other countries?

Cotton arrivals increase in Madhya Pradesh; prices remain stable

Increasing debt and declining landholdings in agriculture, says NABARD survey

How is bamboo fabric better for the environment than cotton?

Stay connected with Ground Report for underreported environmental stories.

Follow us on X, Instagram, and Facebook; share your thoughts at greport2018@gmail.com; subscribe to our weekly newsletter for deep dives from the margins; join our WhatsApp community for real-time updates; and catch our video reports on YouTube.

Your support amplifies voices too often overlooked—thank you for being part of the movement.