Trigger warning: This article discusses suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, please contact a mental health professional.

Eight months ago, in July 2024, Kala Bai’s 40-year-old son drank the dawai—medicine (a colloquial word for essentially anything chemical). “It was around 3 in the afternoon. I had just made tea for him,” she recalled. “Then I heard someone shouting… saying that my son had taken ‘medicine’”. Tears filled her eyes as she repeated in her local Nimari language, “Kai Nayi Maloom Kae Kar Lio—I don’t know why he did this.”

Her son, Shiv Ji Verma, couldn’t be saved. He died soon after in the district hospital.

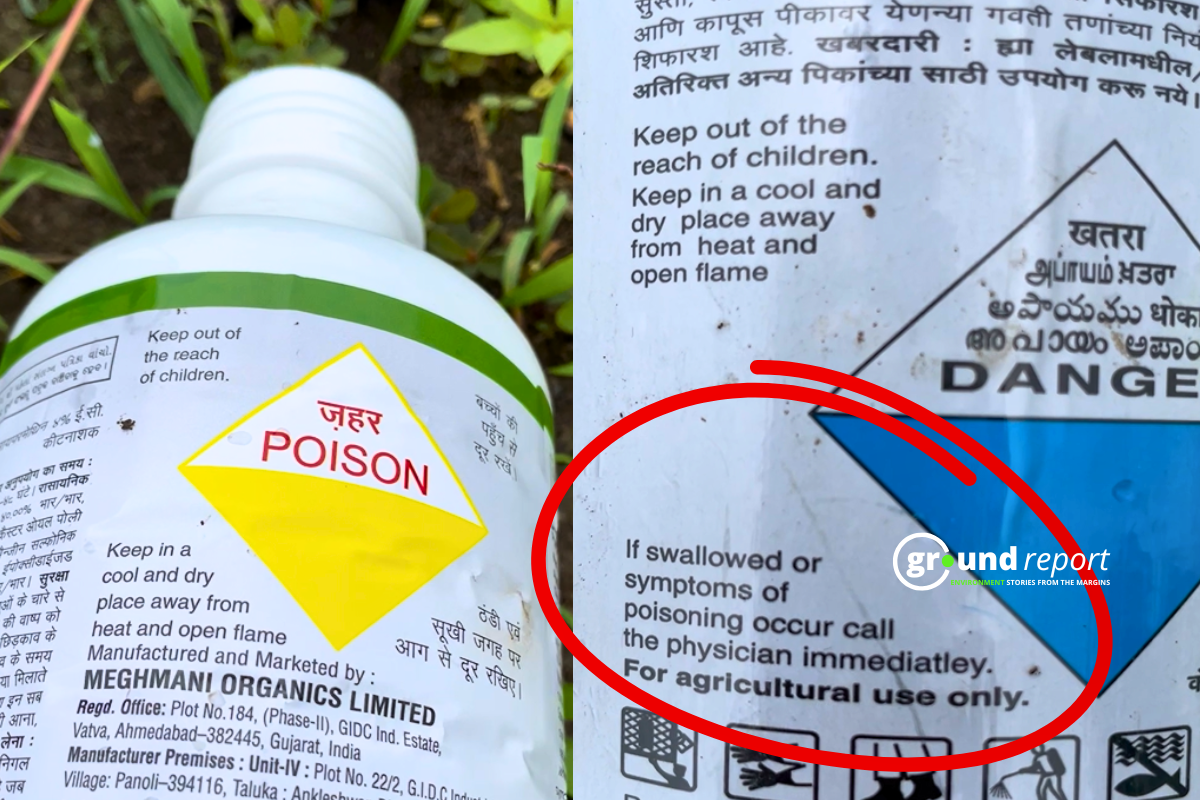

Shiv worked as a daily wage labourer to support the household. He was married twice, but both wives left him within a few months. When asked if he was troubled or under stress, Kalabai simply said, “He was fine; I don’t know why he did this.” The police records at Khargone District Hospital list his cause of death as “drinking medicine”, in this case pesticides– toxic chemicals sprayed on crops to remove pests. Kala Bai’s family doesn’t have any farmland. There is no reason for them to have pesticides at home.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for selling pesticides typically require vendors to maintain detailed records of sales, verify the credentials of buyers, and ensure that pesticides are sold only for legitimate agricultural purposes.

“We ask farmers about their crops, and most of them already know what they need. We provide pesticides based on the crop and the pests that were a problem last season,” explained Vishal Patil, a pesticide trader in Khargone. He, 25, runs a pesticide business in Bishtan, Khargone, for the past three years.

On the other side, the traders often sell without keeping proper records or verifying buyers. Dr. Donthi Narasimha Reddy, a visiting senior fellow at the Impact and Policy Research Institute in Delhi, pointed out that the pesticide industry remains largely unregulated, growing on the anxieties of small and marginal farmers, flawed scientific research, and unscientific agricultural practices.

But, this tragedy has fallen on a family which doesn’t even have any farmland. The extended impact of this unregulated market has been on individuals who shouldn’t have access to these harsh chemicals.

Pesticides kill more than just pests

Professor Michael Eddleston, University of Edinburg, who has worked on pesticide suicides for thirty years, agreed that pesticides are not just a problem for farmers. “Pesticide ingestion is not just a ‘farmer issue’—it is a community issue.”He explained, “Because these toxic chemicals are so easy to get, they don’t just harm farmers. Farm laborers, school teachers, children, and even grandparents are at risk.”

He said, “Many people who drink pesticides do not actually want to die. They do it in distress, but because these chemicals are so toxic, they end up losing their lives.”

India saw the need to regulate pesticides in the late 1950s after cases of pesticide poisoning raised concerns. In 1958, the Madras Poisoning Incident occurred when food got contaminated with BHC (Benzene Hexachloride), causing severe poisoning. This incident exposed the dangers of unregulated pesticide use. In response, the government introduced the Insecticides Act of 1958 to control the import, production, sale, and use of pesticides to protect people and the environment.

However, even with these rules, pesticide-related tragedies continued. In late 1970s, in Kerala’s Kasaragod district, the aerial spraying of the pesticide endosulfan over cashew plantations resulted in numerous health issues like birth defects, physical disabilities, mental retardation, cancer, and gynecological problems affecting not only those directly involved in farming but the entire community.

In India, the 1968 act, along with the Insecticides Rules of 1971, governs the import, manufacture, sale, transport, distribution, and use of pesticides. As per current regulations, all pesticides undergo a rigorous registration process with the Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee (CIBRC) before they can be sold or used. Also, retailers are required to obtain licenses to sell pesticides. For instance, in certain regions, retail outlets must pay a fee of ₹7,500 to acquire a license, which involves submitting specific forms and undergoing periodic inspections by agricultural officers.

Patil’s business runs mostly on credit. Farmers pay part upfront and settle the rest after the harvest. In the case of a new farmer, Vishal notes their name and address but only gives them pesticides if they pay in full. However, he also said that he does not take Aadhaar or any other identity proof from farmers because most of them are people he knows.” On how pesticides reach him, Vishal explained, “A company agent visits us and tells us about the products. Sometimes, we don’t buy what they offer, but if a new product comes in, we purchase it from them.”

Dr Reddy stated, “Pesticides have consistently proven to be a non-factor in agricultural productivity… Pesticides occupy a major percentage of costs in the per acre cost of agricultural production. This is not because of any rise in pesticide prices, but due to the intensive, and unproductive usage of pesticides.”

A. D. Dileep Kumar, CEO of Pesticide Action Network (PAN) India, is a farmer with a degree in zoology and a two-year PG Diploma in Pesticide Risk Management from the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Kumar started researching pesticides and their impact on health and the environment. Kerala’s above-mentioned endosulfan poisoning opened Kumar’s eyes to the devastating impact of these chemicals. Over time, he became an advocate for stricter pesticide regulations and safer farming practices. For him it is simple, the companies which make these toxic chemicals should be held accountable. “If a product harms people, the company should be held accountable. But in India, it is the government that pays compensation, not the pesticide companies,” he said.

Kumar accused pesticide companies of spreading misleading information to increase sales. “Many farmers grow food successfully without using synthetic toxic pest control products. These companies create false claims to convince farmers they need pesticides, even though non-chemical alternatives exist—yet no one is training farmers to use them,” he said.

Shiv was Kala Bai’s eldest son of two sons and two daughters. Her younger son works at a ginning factory in Khargone. She insisted that there was no conflict in the family. “Both my sons lived well together,” she said. Though, now, Kalabai is alone. She gets the government’s free ration scheme by a BPL (below poverty line) card. But with Shiv gone, she has to rely on other villagers.

The case of Shiv G. Verma is not isolated. In India, 65% of pesticide poisoning cases are among adults in India. Nationally, pesticide poisoning is a leading cause of poisoning cases in adults, with the highest prevalence in North India (79.1%), followed by the South (65.9%) and Central regions, including Madhya Pradesh (59.2%).

Despite being in the business of selling pesticides, Vishal admitted, “These chemicals are harmful. They damage the soil. The government should ban them.” In a study published in ScienceDirect, these chemicals have been linked to respiratory diseases, skin problems, headaches, and asthma. For children, long-term exposure can lead to permanent brain damage and memory loss.

Farm workers in the Sagar district, Madhya Pradesh, have reported various health issues due to chronic pesticide exposure. These include headaches (56.5%), muscle pain (51.6%), dizziness (66.1%), blurred vision (35.5%), and skin diseases (19%). The risks are higher for those who smoke, live on farms, or store pesticides at home.

Dr. Reddy said that pesticide poisoning is a hidden crisis affecting thousands across India. Many cases go unreported, and government data fails to capture the full extent of the problem.

Kala Bai recalled how, just months before he died, Shiv cared for her after she fractured her leg in a motorcycle accident. “For three months, I couldn’t walk. He cooked, cleaned, and even helped me use the toilet,” she said, gesturing toward a cot in the corner. “I lay there all day, and he stayed by my side.”

Vishal understands the realities of selling pesticides; it is a chemical eventually. He would too hear these stories of poisoning. Should he be held accountable? Does he think that he is responsible? He responded, “I can’t be responsible for that. If someone is determined to end their life, they will find another way—by drinking something else or by hanging themselves. Who can stop them?”

But we really can.

Prof. Eddleston said that banning toxic pesticides is the only way to reduce deaths. He gives the example of Sri Lanka, where bans on dangerous pesticides saved thousands of lives. He also mentioned China, where pesticide-related deaths dropped from 180,000 per year to 20,000 after restrictions were put in place. Although some rules exist, they are not well enforced.

In 2011, the state of Kerala banned 14 highly dangerous pesticides to protect people’s health. This decision was made after realizing that these chemicals are harmful and can cause dangerous adverse effects to people. While other states still struggle with pesticide poisoning, Kerala’s ban led to fewer deaths without harming farming.

A study by the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention found that Kerala’s ban did not reduce crop production. This proves that farming can continue without using toxic pesticides. Safer options can keep agriculture strong while also protecting people’s lives.

Kerala’s success proves that pesticide deaths are not something we must accept—they can be prevented.

Currently, only the central government can permanently ban pesticides. State governments can only impose temporary bans for 60 days. Kumar believes this is unfair. “States should have the power to ban harmful pesticides permanently. A 60-day ban is not enough,” he said.

The government-based Anupam Verma committee recommended banning several toxic pesticides, yet out of 27 pesticides proposed to be banned in 2020, only three were banned a few years later after several committees examined this matter. “For example, Glyphosate was classified as a carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 2015, yet it is still widely used, and many countries have banned it. But in India, it’s still being used,” he said.

New bill, same old problems

To replace the old 1968 law, the government introduced the Pesticide Management Bill in 2008 in the Rajya Sabha. However, it was not approved and was sent to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Agriculture. Later, in February 2020, the government revised the Bill, and the Union Cabinet approved it. It was introduced again in the Rajya Sabha the following month but was once more sent to the Standing Committee for review.

The Bill includes strict punishments for breaking the rules, such as fines and jail time from two to five years for selling banned or unregistered pesticides, giving false information, or causing serious harm or death. In December 2021, the Standing Committee suggested creating an online system to track pesticide testing and ensuring that all testing labs are properly approved to improve transparency.

Dr Reddy said, “Pesticide Management Bill, as a next step in the process of regulation, is a welcome initiative. However, there are a number of issues, as experienced from 1962, which have not been addressed by this Bill.”

Pesticide Action Network (PAN) India, an organization working on pesticide safety, has raised many concerns and given several suggestions to improve the bill. Kumar argued that the bill has major flaws. He said, “this bill is designed to increase pesticide use and benefit pesticide companies,” he said. “The new bill shifts focus to promoting pesticide business use rather than reducing harm.”

In the previous article, we talked about Nemichand, and Dhamendra. They both spray pesticides without any protective equipment (PPE). The old law required farmers to use protective equipment (PPE), but the new bill does not clearly mention it. “There is a false belief that protective gear can keep farmers safe,” Kumar said. “But studies show that even with PPE, it is almost impossible to use pesticides safely—especially in India’s hot and humid climate.”

Availability of protective equipment is another issue. Kumar described his own experience, “Go to any pesticide shop in India—you might find a pair of gloves, but nothing more.” We wrote in the previous article that it is difficult to breathe under those PPEs, particularly with India’s hot and humid climate it can be suffocating.

“The government knows these pesticides are harmful, but action is too slow. This puts farmers [and communities] at risk,” Kumar said.

Pesticide poisoning is not just a problem for farmers—it affects entire villages. While there are rules about selling and using pesticides, they are not always followed, and dangerous chemicals are still easy to get. Experts like Professor Eddleston and Dr. Reddy believe banning harmful pesticides and finding safer options can save lives. This issue also connects to larger policies, like the farm laws. While those laws focused on selling crops, they didn’t directly deal with pesticide safety. Still, they show how farmers struggle with rules that don’t always protect them.

Kerala has already shown that banning toxic pesticides doesn’t harm farming, it helps people stay safe. If one state can do it, why not the rest of India? Stronger laws, better enforcement, and more awareness can make farming safer for everyone. Pesticides are a public health issue, and the government needs to treat it as well, several people we interviewed echoed this thought. While India’s push towards becoming the biggest agrochemical exporter– currently it is 4th in the world.

“The government needs to act quickly and put public health first. If this bill isn’t improved, it won’t prevent future tragedies,” Kumar warned.

In our first part, we explored the human cost of India’s pesticide consumption. You can read the first part here.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

How much budget BJP govt in Delhi allocate for environmental causes?

Temperature crosses 40°C in seven cities of Madhya Pradesh

Deadly wildfires ravage South Korea, killing at least 24

SC fines ₹1 lakh per tree for illegal felling in Mathura-Vrindavan

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel