In 2020, inside the Maharashtra Assembly speaker’s chamber, farmers, scientists, government officials, and seed companies sat together, debating the crisis that had gripped India’s cotton belt. The farmers were struggling with pest attacks, failing genetically modified cotton crops, and growing debt. Maharashtra state, in India, is infamous for farmer suicides.

Among the attendees was Dr. Narasimha Reddy Donthi, a longtime advocate for sustainable farming and a firsthand witness to the silent suffering in the fields. He recalled that almost all parties blamed the farmers for the failure of Bt cotton—India’s first genetically modified crop. “Farmers didn’t follow the recommended guidelines” was the common reasoning. Dr. Reddy pushed back, “If the farmer is to blame, then why introduce a technology they don’t fully understand or control?”

What is the ‘bt’ in bt-cotton?

A special gene from a bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) was taken and injected into the cotton seed to produce a genetically modified (GM) crop known as Bt cotton. Thanks to this gene, the cotton plant can produce a natural toxin, specifically Bt toxins like Cry1Ac, that specifically targets pests like pink bollworm, which burrows into cotton bolls, damaging fibers and reducing yield. However, over time, some pests, including pink bollworm, have developed resistance.

The idea with Bt-cotton was to remove pink bollworm from the boll of the cotton plant. The only way to do this before Bt cotton was developed was by spraying pesticides, sometimes even 10-12 times. That is bad for both the soil and the person spraying it if the precautions aren’t taken. It was developed in the United States and later tested in China with tremendous results. Before officially coming to India, it was illegally planted.

Dr. Reddy stated, “Bt cotton was introduced illegally by Monsanto before the government even thought of liberalizing cotton. The narrative was built around the idea that it would increase yields, boost exports, and strengthen the textile industry.” Monsanto is a company known for its agricultural products, including genetically modified seeds; it was acquired by Bayer in 2018. After initial tests, bt-cotton was legally adopted in 2002.

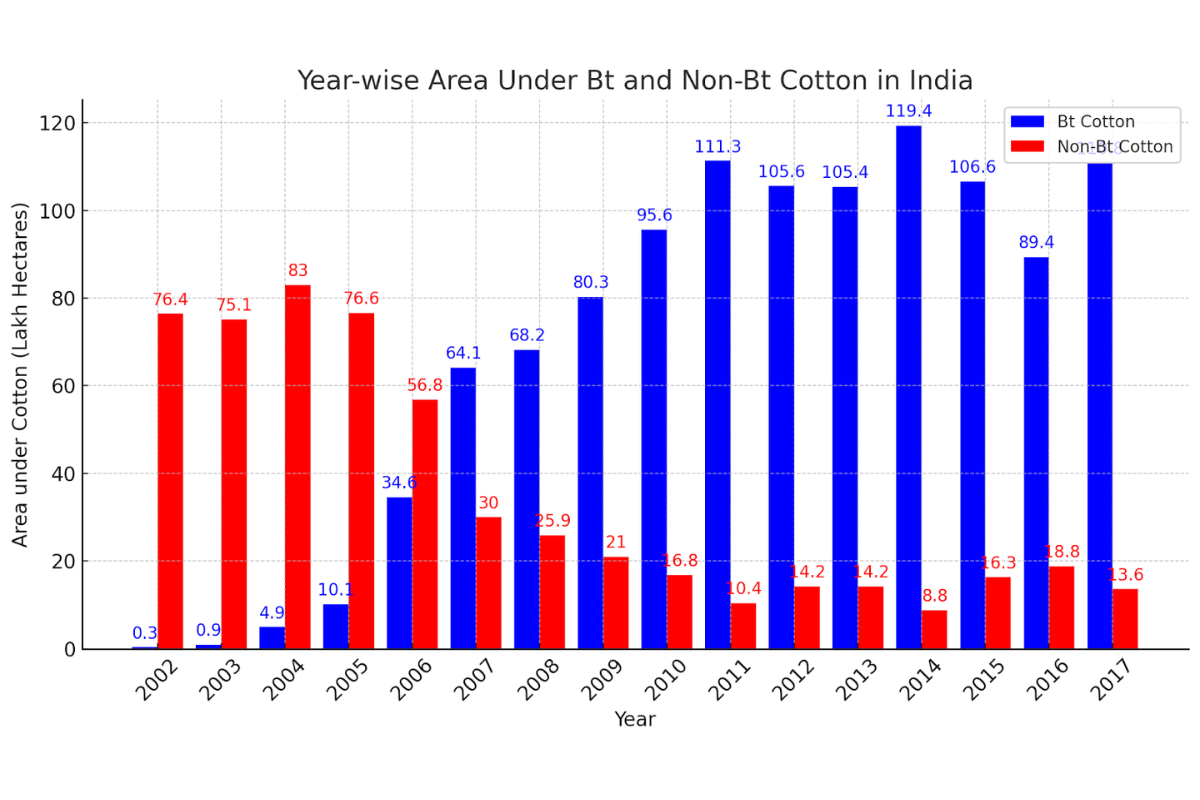

The genetically modified (GM) crops had been introduced in the mid-1990s. While big farms in some developed countries were already using them, many people were hopeful that GM crops could also help small farmers in developing countries. In India, the adoption spread rapidly, and today, more than 90% of India’s cotton fields grow Bt cotton, making the country the world’s largest cotton producer.

While at Washington University in St. Louis, Professor Glenn Davis Stone, an anthropologist, became increasingly interested in how genetically modified (GM) crops were transforming agriculture. When Stone arrived in India in 2000, Bt cotton was still being tested by Monsanto and its Indian partner.

Economists published studies claiming Bt cotton increased yields and reduced pesticide use, making it a great success. But Stone kept returning to India every year—supported by two grants from the National Science Foundation—and saw that the situation was much more complicated. For an article, he pointed out, “major scientific journals declared Bt cotton to be a ‘winner’ for India even before Indian farmers began to adopt it.”

Among the major cotton-growing states, Gujarat had the highest area under Bt cotton, increasing from 22.84 lakh hectares to 24.84 lakh hectares, with production rising from 75.09 lakh bales to 87.95 lakh bales. Maharashtra had the largest area under cultivation (41.82 lakh hectares) in 2022–23 but recorded a lower yield of 338 kg per hectare. Rajasthan saw an increase in both area and production, with yield rising from 558 kg per hectare to 579 kg per hectare.

But, over the past 15-20 years, problems have emerged.

“Every time a new hybrid is introduced, it gives good yields for the first few years. But then, the yields decline,” Dr. Reddy explained. “This happened with Bt cotton as well. Initially, it showed good results, but when the yields started dropping, the technology was not updated. The same seeds are still being pushed, even though their effectiveness has long diminished.”

Decades later, in 2019, Stone met Dr. Keshav Raj Kranthi, one of India’s leading experts on cotton agroecology and former director of the Central Institute for Cotton Research. They decided to work together to examine how Indian cotton farming had changed over the past two decades. Their research led to the study Long-term impacts of Bt cotton in India, published in Nature Plants.

Their study in 2020 looked at 20 years of data and found that while Bt cotton still controlled the American bollworm, another pest—the pink bollworm—became resistant to it. As a result, farmers had to use more pesticides than before. The study also found that the increase in cotton yield was more due to the use of fertilizers, along with expanded irrigation infrastructure, than to Bt cotton itself.

Dr. Reddy explained, “For an average farmer, yield is not the biggest issue. Yield is dynamic—it depends on soil, weather, management, and many other factors. The seed companies claimed Bt cotton would give higher yields, but what they really meant was that it would prevent some bolls from being eaten by pests. So, the so-called higher yield is not because the plant produces more bolls but because fewer are lost to pests.”

In 2002, Glenn Stone began his fieldwork in India’s cotton-growing regions, focusing on smallholder farmers in Andhra Pradesh; his research primarily took place in the Warangal district (now in Telangana). From 2000 to 2008 (different visits to India during this period), Stone immersed himself in local communities to understand the impact of GM cotton adoption

The bigger trap, than pesticide usage

In fact, a 2015 study published in Environmental Sciences Europe found a direct link between the rise in Bt cotton use and farmer suicides in India’s rain-fed areas. Researchers used physiologically based demographic models (PBDMs) to study how weather, planting density, and pests affect cotton yield. They divided India into 2,855 grid cells, which means divided into equal-sized square sections, and analyzed daily weather data from 1979 to 2010.

The study highlighted that the high cost of Bt cotton seeds, along with ecological disruptions and crop failures, pushed many farmers into deep financial distress. This rising pesticide use has also increased farming costs. One of their key findings was that cotton yields had already started rising before Bt cotton was widely adopted. The biggest jump in yields happened in 2003-2004, even though Bt cotton was still used by only a small percentage of farmers. If Bt cotton were responsible for these higher yields, the data should have shown a clear link—but instead, the increase was mostly due to higher fertilizer use and the introduction of new insecticides.

The issue was bigger than pests. Farmers were spending more money on seeds and pesticides, but their crops were failing and their soil was getting weaker. Many can’t even afford proper food. “We don’t just see numbers,” Dr. Reddy said. “We see hunger in cotton fields. People grow cotton but can’t afford to eat.”

In an agrarian society like India, almost 90% of farmers are smallholders, i.e., they have less than 2 hectares of land.

The costs and uncertainties in farming are so severe that a study by the Institute of Social and Economic Change found that one-third of the 321 farmers who died by suicide in Karnataka in 2014 were cotton or tobacco growers. In Belagavi and Haveri, cotton farmers could produce only 45% of their expected yield, adding to their financial struggles.

Adaptation–Mutation

The pink bollworm has returned and is now resistant to Bt cotton’s toxin. New secondary pests that Bt cotton does not protect against have also started damaging crops. Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall have further weakened crops in India. As a result, farmers have again increased pesticide use, trying to control these new threats. The Bt cotton market is a significant global market, with projections indicating a substantial increase in value, reaching US$3.912 billion in 2029 from US$2.832 billion in 2024.

Similarly, a 2017 report from the Coalition for a GM-Free India pointed out that cotton production has not increased much in recent years. At the same time, pesticide use has more than doubled, rising from 4,600 metric tons in 2006 to 11,598 metric tons in 2013. Farmers also spend more money on chemicals, and the focus on Bt cotton has reduced the variety of crops grown in some areas.

A study by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and the Central Institute for Cotton Research (CICR) found that Bt cotton produces 3 to 4 quintals more per acre compared to traditional cotton. On average, farmers growing Bt cotton in rainfed areas earn about ₹25,000 more per hectare if they follow proper farming methods. Bt cotton cultivation in India has grown over the years, covering more land and increasing production.

Debunking success myth

Furthermore, nationwide data reveals that cotton yields have stagnated over the past 13 years. Currently, Indian cotton farmers are spending more per hectare on insecticides than they did before the widespread adoption of Bt cotton, highlighting the increasing economic burden on farmers.

The impact of Bt cotton in India is complicated. Some studies show that it helps farmers by increasing yields and profits when farming conditions are good. However, other reports highlight problems like pests becoming resistant, farmers using more pesticides, and many struggling with debt. These mixed results show that while Bt cotton has some benefits, it also has risks. It’s important to look at both sides carefully before making decisions about using such technology in farming.

However, Dr. Reddy pointed out that government policies had remained unchanged despite the growing crisis. “The government has not changed its course on Bt cotton. The same arguments continue. They themselves said that hybrids should be changed every three years, but they have not done that in over 20 years. Why? Because there is a commercial interest behind it.”

Data from 2020-2021 highlights India’s lagging cotton yields, with an average national yield of 466 kg/ha compared to the global average of 774 kg/ha. Although insecticide use initially declined after the introduction of Bt cotton, resistance development in pests has led to increased chemical applications. By 2012, hybrid Bt cotton adoption in India had surpassed 90%, but the high costs of hybrid seeds have remained a burden for farmers. In 2020, the price of hybrid Bt cotton seeds in India was nearly $31.50 per hectare, significantly higher than non-Bt non-hybrid pure-line seeds, which cost around $7-8 per hectare.

Dr. Reddy put it simply, “The consequences of using Bt cotton for 20 years? More farmer suicides, more debt, and lower cotton quality.” His words reflect the harsh reality—what was supposed to help farmers has instead made their situation worse.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

What is pesticide selling—protection from pests, and vulnerability to accidental poisoning

What is human cost of India’s pesticide consumption, and lack of regulations

Why does India use lower Pesticides per hectare of cropland than other countries?

Fighting for breath: Khargone’s cotton workers battle Byssinosis

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel