Sukri village resident Premsingh Uike recalls the day he and his family were forced to leave their ancestral land in the Kanha Tiger Reserve in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

“We received some money, but we are lost, wandering in search of livelihood. There’s only sorrow here; we need the forest,” he says, highlighting the condition of his community, displaced under the a tiger conservation project.

Uike’s family is among 450 households allegedly evicted in June 2014 from Sukri and neighbouring villages—Jholar, Azanpur, Bithli, Benda, and Rol—to expand the tiger reserve. According to Uike, this was done without obtaining Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from the villagers, nor were they offered adequate land or compensation to rebuild their lives.

“The entire village was harassed for years to leave the forest land. After being evicted, we received neither land nor help to settle elsewhere. To this day, we’ve received only a fraction of the promised compensation,” he alleges, capturing the ongoing struggle of communities bearing the costs of tiger conservation.

Another displaced villager, Subelal Baiga, echoes a similar narrative:

“The forest department officials threatened us and forced us to sign documents. They even threatened to trample our homes with elephants.”

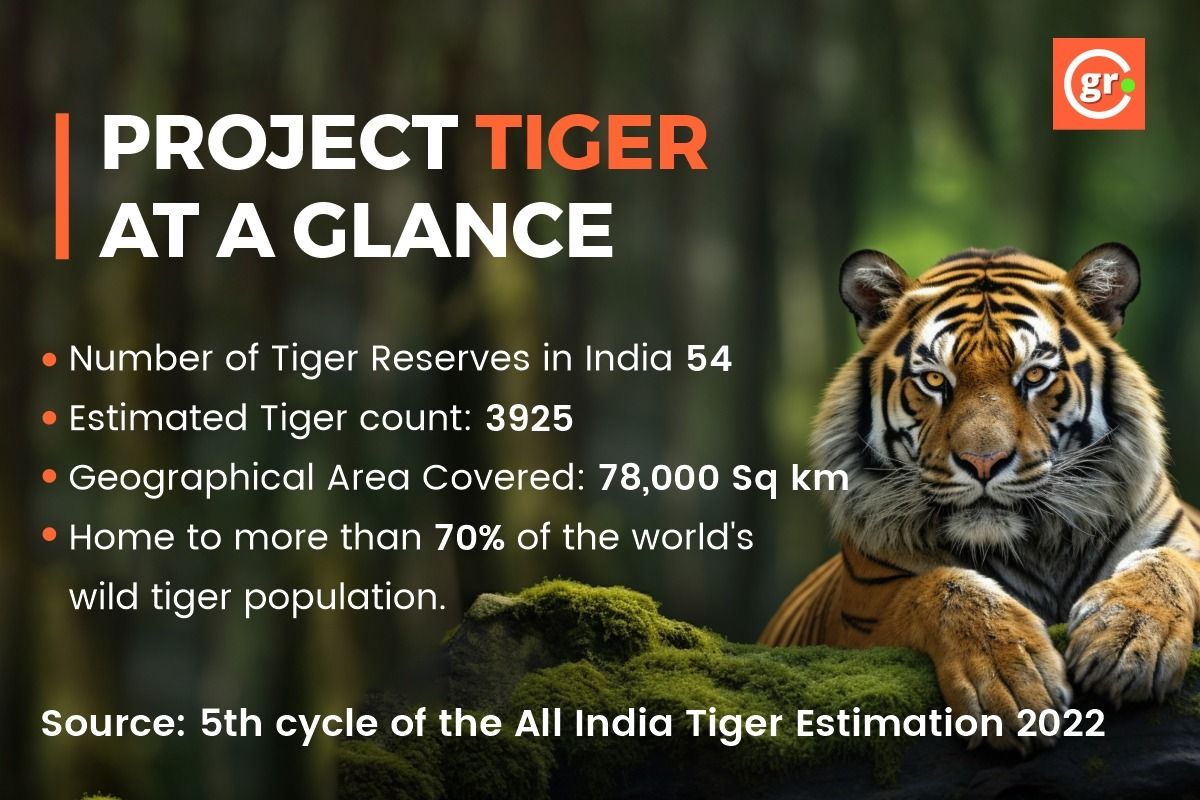

In 2024, India’s Project Tiger completed 51 years. Launched in 1973 by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government to save tigers, that same year the tiger was added to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List. Initially, nine tiger reserves were established to conserve tigers, but this number has now increased to 54.

Among these initial nine tiger reserves was Madhya Pradesh’s Kanha Reserve, founded on the lands of the Baiga and Gond tribes. For this, around 650 families from 24 villages were displaced outside the reserve boundaries.

According to a 2013 Lok Sabha reference note, approximately 600,000 people living in forests across India were displaced by 2007 due to the establishment of wildlife sanctuaries and national parks. Meanwhile, government approval for development projects that damage forests and biodiversity laws that harm ecological diversity continued to be passed.

Project Tiger officials view India’s conservation efforts as essential and effective, but critics call it a “fortress model” that excludes local communities from forests. Yet, many cases show that, with government support, these communities have successfully managed forests, even boosting tiger populations. The government’s promotion of eviction policies for conservation raises critical questions

Indigenous Opposition to Displacement

A report published by the Indigenous Rights and Protected Areas Initiative at the University of Arizona reveals that post-2021, the number of people displaced from tiger reserves in India increased by 967%. The report estimates that approximately 2.9 million people have been displaced since 2021.

Letters obtained through an RTI reveal that on June 19, the Director of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) sent a letter urging the chief wildlife wardens of 19 states to evict more Indigenous people from tiger reserves.

The letter states that around 591 villages, comprising 64,801 families, are still residing in the core areas of 54 tiger reserves. The progress in relocating these villages is very slow, which is a serious concern for tiger conservation.

Following the release of this letter, Indigenous communities across the country have protested. In September, 154 activists, including several conservationists, submitted a memorandum to Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav, expressing shock at the NTCA’s actions, which they claim violate all relevant laws by ordering the displacement of forest-dependent communities.

This move by the NTCA, along with its directive for relocation, constitutes a violation of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (2006), the Forest Rights Act, 2006, the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR), and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

Wrong Focus?

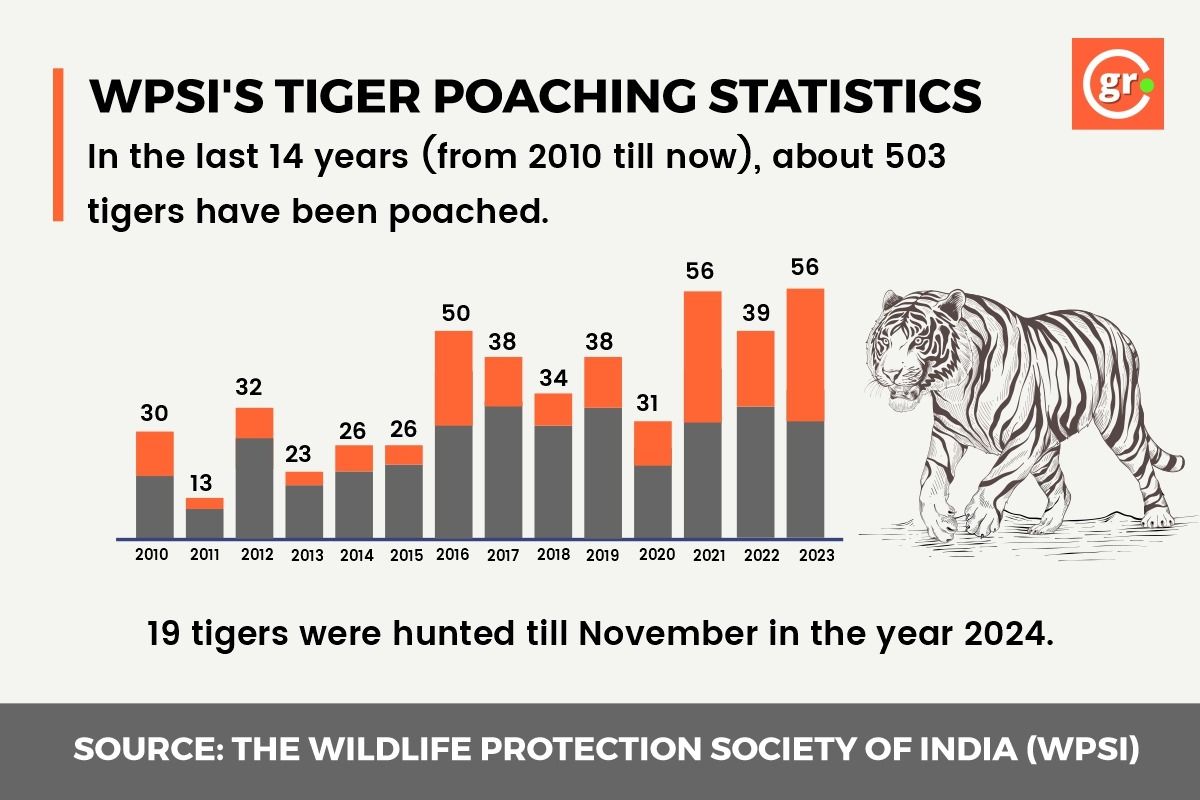

Despite large-scale relocations under Project Tiger, India’s tiger population continued to decline, dropping below 1,500 in 2006. Tigers went extinct in Sariska and Panna, leading the NTCA to reintroduce tigers from other reserves. This raises concerns about the direction of tiger conservation. Critics argue that authorities focused on evicting Indigenous communities instead of addressing poaching, habitat destruction, and urbanization—key threats. Over the past 14 years, approximately 503 tigers have been illegally poached, fueled by demand from Asian markets.

The Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI) works closely with government enforcement agencies to catch tiger poachers and traders in India. WPSI collects data from reports received from enforcement officers, work done by WPSI, and other sources.

These figures represent only a fraction of the actual illegal poaching and trafficking of tiger body parts in India.

Big Money for Big Cats

“Big cats mean big money, which is probably why efforts are being made to create tiger reserves even in places where tigers are not present and local tribes are being illegally evicted. If they enter the reserve, they face the risk of beating, extortion, or jail in the name of forest crimes. On the contrary, thousands of tourists are welcomed and hotels and restaurants are flourishing,” says Sharachchandra Lele of the Bangalore-based Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE).

Supporting Lele’s statement, Research and Advocacy Officer of Survival International, Fiore Longo says that

“It is true that big money is being made in the name of big cats. This money is being raised in the form of donations by big conservation groups like the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) which supports tiger conservation in India. These groups are raising money by showing the number of tigers in Western countries and pictures of smuggled body parts. You can imagine that WWF alone earns $2 million per day.”

According to Suhas Chakma, co-author of the report ‘Tribes Get Out, Tourists Welcome’, notifying an area as a tiger reserve has become a means of displacement. He explains that

“Not a single tiger was found in five tiger reserves of India (Sahradri, Maharashtra, Satkosia, Odisha, Kamlang, Arunachal Pradesh, Kawal, Telangana and Dampa, Mizoram) but a total of 5,670 tribals were displaced from here. When there are no tigers, why was there displacement?”

The Chenchu tribe, whose forest is now divided into the Amrabad Tiger Reserve, has been living with wild animals for generations. Jenuk Chenchu of the Chenchu community says

“We were evicted from our ancestral homes saying that we make too much noise, which harms wildlife, while rich people are being taken around the forest in loud jeeps and cars.”

According to figures, more than 26 lakh tourists visited the National Parks and Tiger Reserves of Madhya Pradesh alone in the year 2023, due to which the forest department earned about Rs 55 crore.

According to the tiger census of the year 2018, Madhya Pradesh has the highest number of tigers in the country, 526, while now their number has increased to more than 785.

He further says “Tigers are like our elder brothers, they help us. If a tiger eats a wild animal, it will eat a part of it and leave a part for us. When we go to collect food, birds help us, they tell us whether there is any dangerous animal nearby or not.”

According to Sharachchandra Lele, the Indian Tiger conservation model is to map legally protected areas and patrol their boundaries with guards. Some reserves have armed guards who can be given the right to shoot at sight. Money donated by the tiger-loving public is used to train and equip these guards. This is known as fortress conservation.

For example, in Kaziranga National Park in Assam, forest rangers are allegedly empowered to shoot at poachers. This, tribals allege, has led to the killing of many innocent people. According to a BBC report, in 2015, the number of people killed by park guards was higher than the number of rhinos killed.

Rehabilitation policy, forced to earn a living through labour

A tiger reserve has a core area where forest dwellers are prohibited from grazing livestock, collecting wood, and gathering forest produce. There is a buffer zone surrounding this core, and forest officials frequently impose time and location restrictions on such permissions.

In Rajasthan’s Sariska Tiger Reserve, the first rehabilitation took place in 1976–77, but after some families were given non-arable land as compensation, they returned to the sanctuary. This voluntary resettlement program was also hindered by the lax attitude of forest officials.

Similarly, in 2012, Gujjar pastoralists removed from Rajaji Tiger Reserve, who traditionally relied on buffalo herding, were encouraged to take up farming on new land, provided with water pumps and electricity. However, due to limited farming experience and the loss of traditional income sources, many indigenous people faced hardships.

Successful stories amidst displacement

In Karnataka’s Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Tiger Reserve (BRT), the Soliga tribes chose not to relocate despite compensation, instead focusing on removing invasive plants and stopping illegal hunting. As a result, tiger populations in BRT doubled between 2010 and 2014.

Tribes like the Soliga, who have been recognized for their rights in tiger reserves, share a deep connection with the forest. Survival International’s director, Steve Corry, argues that forcibly removing tribes from these reserves is not only unlawful but detrimental to the forests and wildlife.

In Kerala’s Parambikulam Tiger Reserve, communities not relocated found work as tour guides and forest guards. Their involvement in activities like honey collection helped improve their income and reduce grazing pressure on the forest.

In Madhya Pradesh’s tough terrain, local tribes helped the forest department curb poaching, and tribal assistance was vital in catching an interstate poaching gang in September.

Environmental activists, including Rashid Noor Khan, assert that the increasing tiger population near Bhopal proves that humans and tigers can coexist without displacing indigenous communities, who have long cared for both wildlife and the forest.

However, the push for tourism has led to forced relocations while development projects in protected areas continue. According to the NTCA, new government approvals for construction in eco-sensitive zones raise concerns about increased displacement and ecological damage.

Changes in rules lead to exploitation

While forest dwellers face forced evictions, tourism-driven construction in protected zones is on a surge, with rising encroachments on community spaces.

In 2022, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) approved 401 projects, including 517 requiring forest land diversion. By August 2023, 40 of 53 proposed projects in eco-sensitive zones around protected areas had been cleared.

In April 2023, the Supreme Court modified its earlier directive, now allowing conditional development in eco-sensitive zones, previously set as a mandatory 1-kilometre buffer around national parks and wildlife sanctuaries with an activity ban.

Environmental activist Rashid Noor Khan warns that such projects risk more displacements and alter landscapes. Dense forests are being converted into grasslands, disturbing species balance, while the NTCA reports that mining harms flora and fauna in these areas.

Way ahead

India currently has around 3,682 tigers, yet Project Tiger reveals that conservation cannot rely solely on relocation. Officials suggest declaring 38 million hectares of forest outside reserves as “tiger corridors” to allow tigers to migrate between habitats, reducing breeding risks and supporting conservation.

The RRAG report, however, raises concerns over displacement. At ₹15 lakh per family, relocating 452,189 people would cost ₹15,2766 million (US$1853 million), but suitable land for these families is scarce. Expanding corridors without adequate rehabilitation plans could pose significant challenges for displaced communities.

Tribal rights activist Suhas Chakma warns that large-scale displacement will hinder human development, as state authorities may hesitate to initiate development projects for involuntarily relocated communities. He advocates for a model like Karnataka’s Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Tiger Reserve, where scheduled tribes and tigers coexist, fostering mutual development.

Lele of ATRE agrees, noting that although there are successful examples of forest dwellers and wildlife coexisting in India, the government’s relocation policies persist. Despite the 2006 Forest Rights Act recognizing the role of tribals in forest conservation, forced evictions continue, often in contravention of this law.

Similarly, Vidya Athreya, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society, emphasizes that successful wildlife conservation in India relies on the involvement of local communities. With numerous examples of harmonious coexistence between big cats and humans, she believes that integrating these community-based models is essential for strong, effective conservation efforts.

Meanwhile, Uike and other displaced villagers cling to the hope that one day they, or future generations, might be allowed to return to the forests. However, this hope faces significant challenges. State governments remain reluctant to grant forest rights to local communities, while large-scale displacement looms under the Tiger Corridor Project, which aims to connect sanctuaries for tiger movement. This initiative threatens to displace thousands of forest-dwelling communities.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Mystery Shrouds Death of 10 Elephants in Bandhavgarh: Timeline

Pench: ‘Trees for Tigers’ to curb human-wildlife conflict

Why is Lesser Florican nearing extinction in Madhya Pradesh?

Mountains Await First Snow: Understanding the Delayed Winter

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.