Seeds. Manure. Fertilizers. Pesticides. To my mind, these are the four tenets of agriculture. Every farmer will use all these four essential items, particularly in an agrarian society like India. India’s use of pesticides per hectare is significantly lower than that of other major agricultural economies such as the United States, China, and Brazil. This seems like a good trend, but there is something more to this entire pesticide dichotomy.

Let’s try and answer the question.

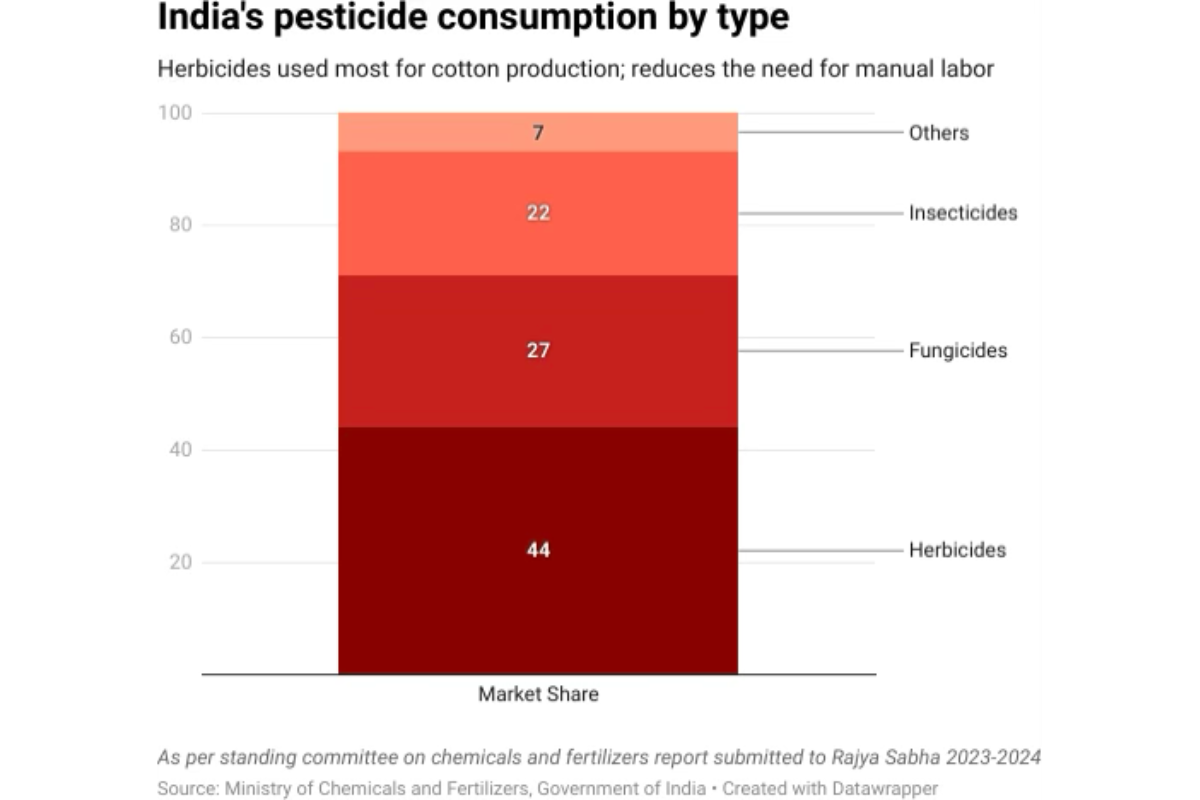

Jagdish, from Raipura, in the Sehore district, had sown wheat crops for the rabi season. He used fertilizers—one bag of diammonium phosphate (DAP), three bags of urea, three bags of super manure, and more potash. When we asked about pesticides, he said he had sprayed illimar (an insecticide) only once, for which he spent Rs 5000/acre. The 65-year-old Karan Singh of Neelbad village in Ichhawar Tehsil said, “He never uses pesticides in his fields.” However, for the past few years, he has started using weedicides/herbicides. He explained that finding labour to remove weeds by hand is difficult, and even if he finds workers, he has to pay a high price for them. As per the government data, India uses herbicides the most to kill weeds.

The word pesticides is derived from the Latin pestis (plague) and caedere (kill). Essential: these are the chemical compounds used to kill any pest organisms that threaten crops. I am using the word kill loosely—this includes repelling, reducing, etc. Pesticides are of several kinds: insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, rodenticides, etc. While the fertilizers are chemicals mostly potassium (K), ammonia (A), and phosphorus (P), nutrients necessary for soil health.

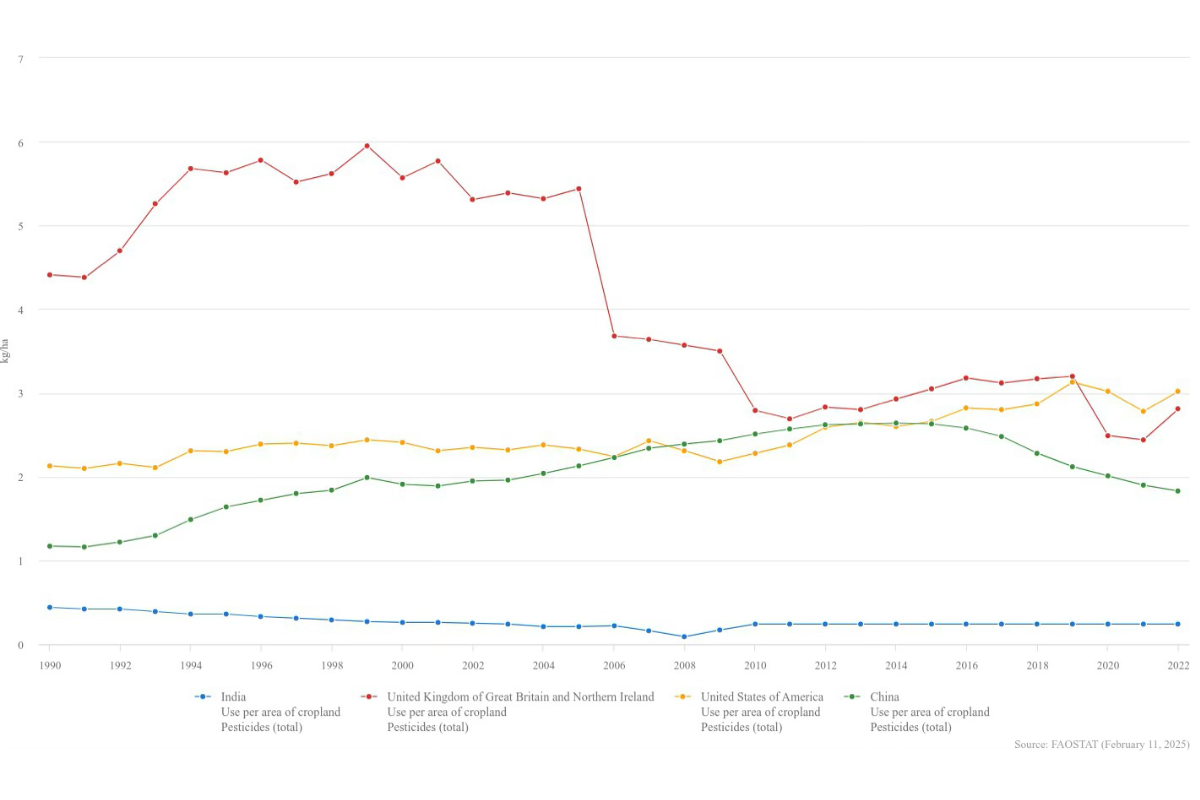

Coming back to the question, major countries like the United States of America, China, the United Kingdom, and India have stark differences in pesticide consumption per area of cropland. India consistently uses 0.2 kg/hectare of pesticides, while the US fluctuates between 2 and 3 kg/hectare. The United Kingdom had the highest consumption per hectare, at 6 kg/hectare, but its consumption has drastically declined.

A 2017 report stated that India lost 18–24% of its annual crop yield to pests, worth USD 36 billion. With climate change bringing new pest outbreaks, this number has likely risen in recent years. So, there are pests. Jagdish says that he has to use more pesticides in the soybean crop, as it is more prone to diseases and pests. In the 2024 Kharif season—June to September—he spent Rs 15000/acre. And erratic rainfall reduced his yield to just one quintal per acre. Pesticides are expensive, and for Jagdish, it becomes difficult to recover costs

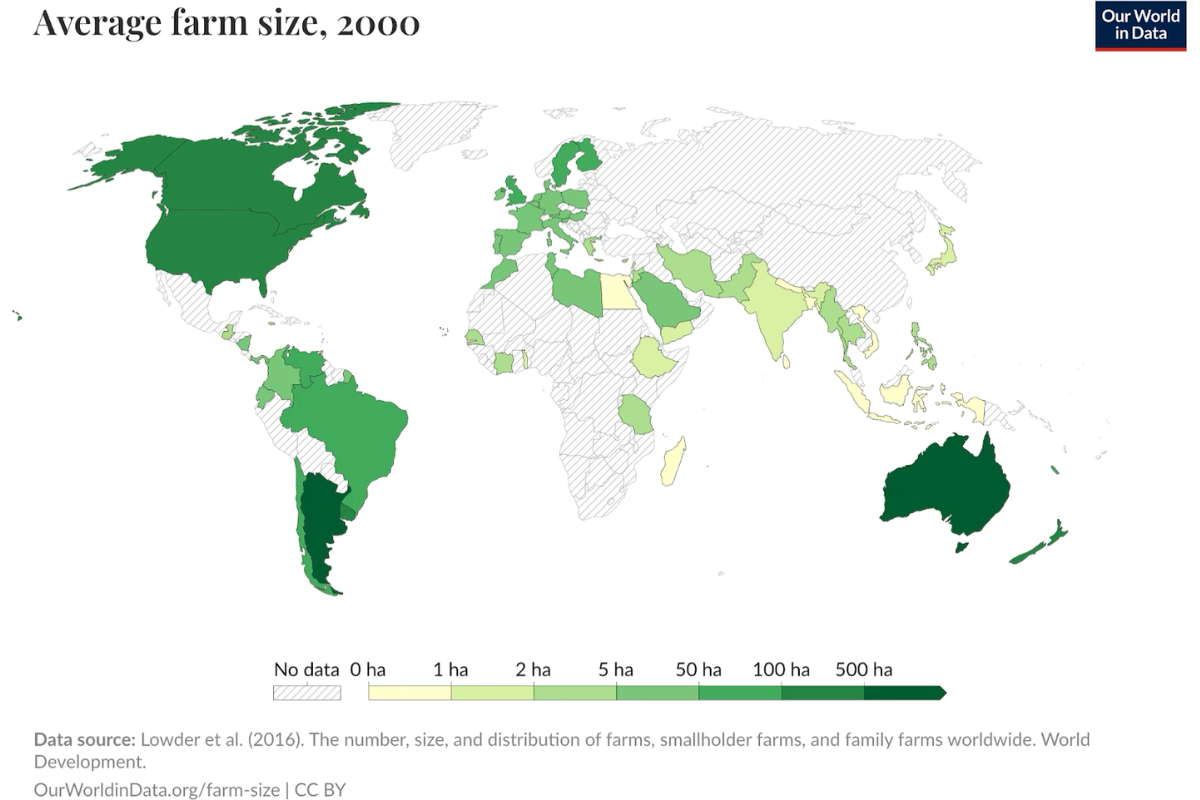

Dr. P. Indira Devi, ICAR Emeritus Professor at Kerala Agricultural University, underlines certain reasons. She said, “…differences in the types of crops grown and farming practices… Many Indian farmers still rely on subsistence farming rather than extensive commercial farming.” According to the National Sample Survey Office, almost 90% of rural agricultural households in India own less than two hectares of land. These smallholder farmers often cultivate crops primarily for subsistence rather than for large-scale commercial markets. The average farm size. In India, it is 1.3 hectares, and with increasing population and fragmentation, the average farm size would decrease. While in the US the size is 178 hectares.

Neelbad, a region in the Ichawar block of Sehore district, faces severe water scarcity for irrigation, leaving most farmers reliant on rainwater. Jitendra, who cultivates four acres of land, explains that pesticides and fertilizers work effectively only with sufficient water. As a result, farmers here grow only drought-resistant crops, relying on cow dung manure instead of fertilizers, let alone pesticides.

Accessibility and affordability are two reasons behind this disparity in usage. Dr. P. Indira Devi’s 2015 paper states that 90% of pesticide sales happen through private retail shops. She said, “But what I could observe is that the private players—mostly, not mostly, the majority sell of chemical pesticides is by companies.”

Arjun Singh, a farmer from Raipura village, explained it this way. He said we get fertilizers and seeds from the government society, where subsidies make fertilizers like DAP and urea more affordable than market prices. However, pesticides are mostly available through private shopkeepers. They explain that cereal crops like gram and wheat require minimal pesticide use, whereas crops like vegetables and soybeans need a significant amount.

Arjun’s explanation leads us to a few fascinating questions. First—what’s the state-wise consumption of pesticides? Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra consume more pesticides per hectare than the all-India average. These states have many affluent farmers.

Second, what crops are these pesticides used most in? As per FICCI’s 2016 report, in India, pesticide treatment is most common for fibre crops like cotton, covering an average of 65% of the cultivated area. This is followed by fruits (50%), vegetables (46%), spices (43%), oilseeds (28%), and pulses (23%).

Even with low consumption, the recent incidents with two spice brands highlight certain concerns of pesticide residue. Recently, two Indian spice brands had their shipments rejected from Hong Kong due to contamination with ethylene oxide, a chemical linked to

pesticide residues. Even Qatar rejected India’s species. Both countries have strict regulations to check for pesticides, while in India nothing of this kind exists.

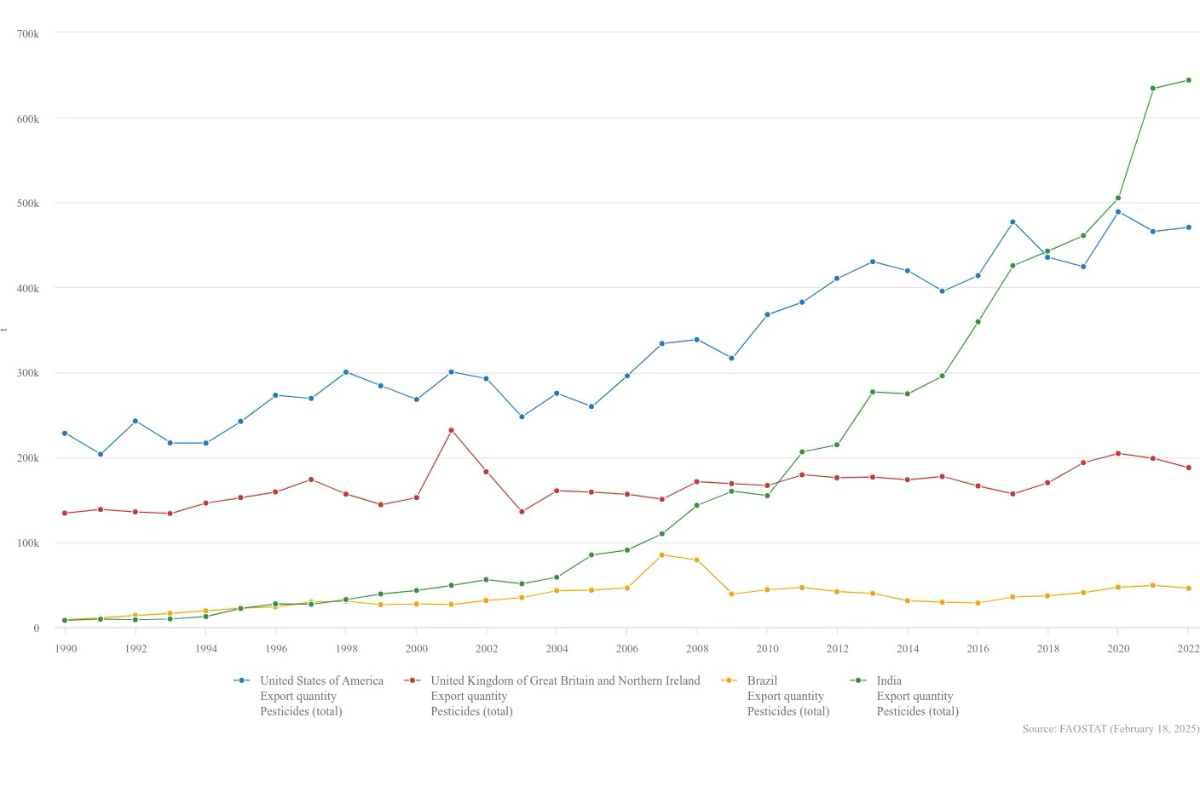

Experts raise another concern. India’s domestic pesticide consumption is low, but the country has emerged as a major exporter of agrochemicals. Since 2008, pesticide exports have skyrocketed, making India one of the world’s leading producers. So, India might not be consuming the pesticides for the reasons explained above but is exporting them. The former Union Agricultural Minister, Dr. Narendra Singh Tomar, said, “India is the world’s fourth-largest agrochemical producer.” In his speech, he highlighted that the chemicals industry has immense growth potential, particularly with climate change’s direct link with pests.

Experts fear that this production comes with significant environmental concerns. With policy and enforcement limitations, the companies discharge toxic chemicals into nearby water bodies and soil, leading to long-term ecological damage. And, when farmers irrigate their crops with contaminated groundwater, it further contaminates the crop even if pesticides aren’t used.

Dr. Devi adds, “It is important that we take into consideration the extenalities of chemical pesticide spray with respect to human health impacts, ecosystem damage and trade impacts . When we estimate the costs of these externalities along with the direct costs of chemical and application costs and compare with yield benefits , the economic justification may often be at stake.”

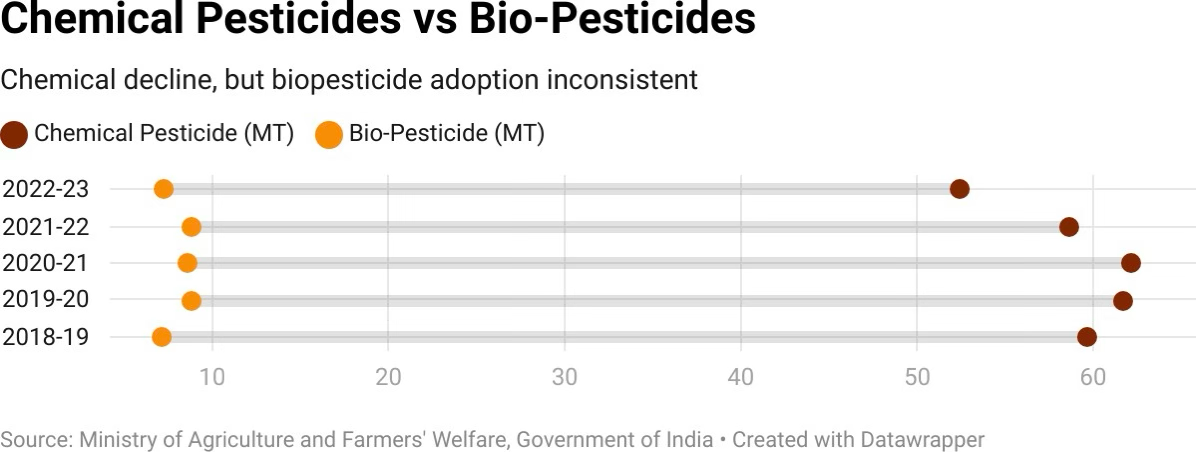

There are several related concerns with pesticides, even if the per-hectare consumption is low. From pesticide residue, as mentioned above, to pesticide poisoning. To tackle such issues, the government has brought biopesticides. The implementation and acceptance of these new eco-friendly chemicals have been slow.

India’s pesticide demand-supply is regulated by the Insecticides Act of 1968. There have been several attempts to update the act, for instance, through the Pesticide Management Bill of 2020. The consumption of pesticides is low, but concerns persist with their production and the type of crops they are used for. There is a need to consider the harmful effects of pesticides and the agrochemical industry on the environment and, at the same time, on the consumer. The question unravels other important aspects of India’s agricultural ecosystem’s socio-economic state.

In our next article, we will delve deeper into the disproportionate burden of deaths caused by pesticide poisoning and explore whether stronger regulations could help prevent these tragedies, as Kerala did.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

California Fires Live updates: destructive wildfires in history

Hollywood Hills burning video is fake and AI generated

Devastating wildfire in California: wind, dry conditions to blame?

Los Angeles Cracks Under Water Pressure

From tourist paradise to waste wasteland: Sindh River Cry for help

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.