While presenting the Union Budget on February 1, India’s Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, emphasized the promotion of pulse crops, announcing the Mission for Aatmanirbharta (Self-Reliance) in Pulses. This six-year initiative will focus on pigeon pea, black gram, and red lentil.

A budget of 1000 crore rupees has been allocated for this mission in this year’s Union Budget 2025-26. The money will be used for warehouse expansion to ensure the purchase of these three pulse crops at MSP and their proper storage. The Finance Minister said that maximum procurement of pulses from farmers will be ensured by NAFED (National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India) and NCCF (National Cooperative Consumers’ Federation of India).

“Ten years ago, the government took concrete steps to achieve near self-sufficiency in pulses. Farmers expanded cultivation by 50%, while the government ensured procurement and fair prices. Since then, rising incomes and affordability have significantly increased pulse consumption,” Sitharaman explains.

Over five hundred kilometers from New Delhi, Anokhilal Nagar, a farmer from Obedullaganj in Raisen district, Madhya Pradesh, is heading home after irrigating his wheat fields. It’s been 10 days since the Finance Minister presented the budget, which proposed several benefit schemes for farmers like him. However, the 70-year-old has no knowledge of these announcements.

When the reporter informed Nagar that the government plans to allocate Rs 1,000 crore to promote pulse crops, he simply replied,

“What are we supposed to do? What is the government doing? We don’t know anything.”

For Anokhilal, growing pulse crops is now a thing of the past. Having farmed for 55 years, he currently cultivates on 9 acres. In the past, he grew crops like tevda and lentils, but he explains,

“We stopped growing them because the crops were affected by the ukhta disease.”

Anokhilal is not alone. Many farmers of Obedullaganj used to cultivate pulse crops earlier. However, due to the Wilt disease locally called Ukhta, they stopped growing these crops. They are not even looking at the recent government announcements with much hope.

The launch of the Mission for Aatmanirbharta in Pulses offers little hope to farmers in the state. Despite being the world’s largest producer and consumer of pulses, India is grappling with rising imports and stagnant domestic production. Farmers still cultivating pulses, as well as those like Anokhilal who have stopped due to wilt disease, remain skeptical of government schemes. They point to the failure of past initiatives to address the ongoing crop disease that continues to devastate pulse production.

India: world’s largest producer and importer

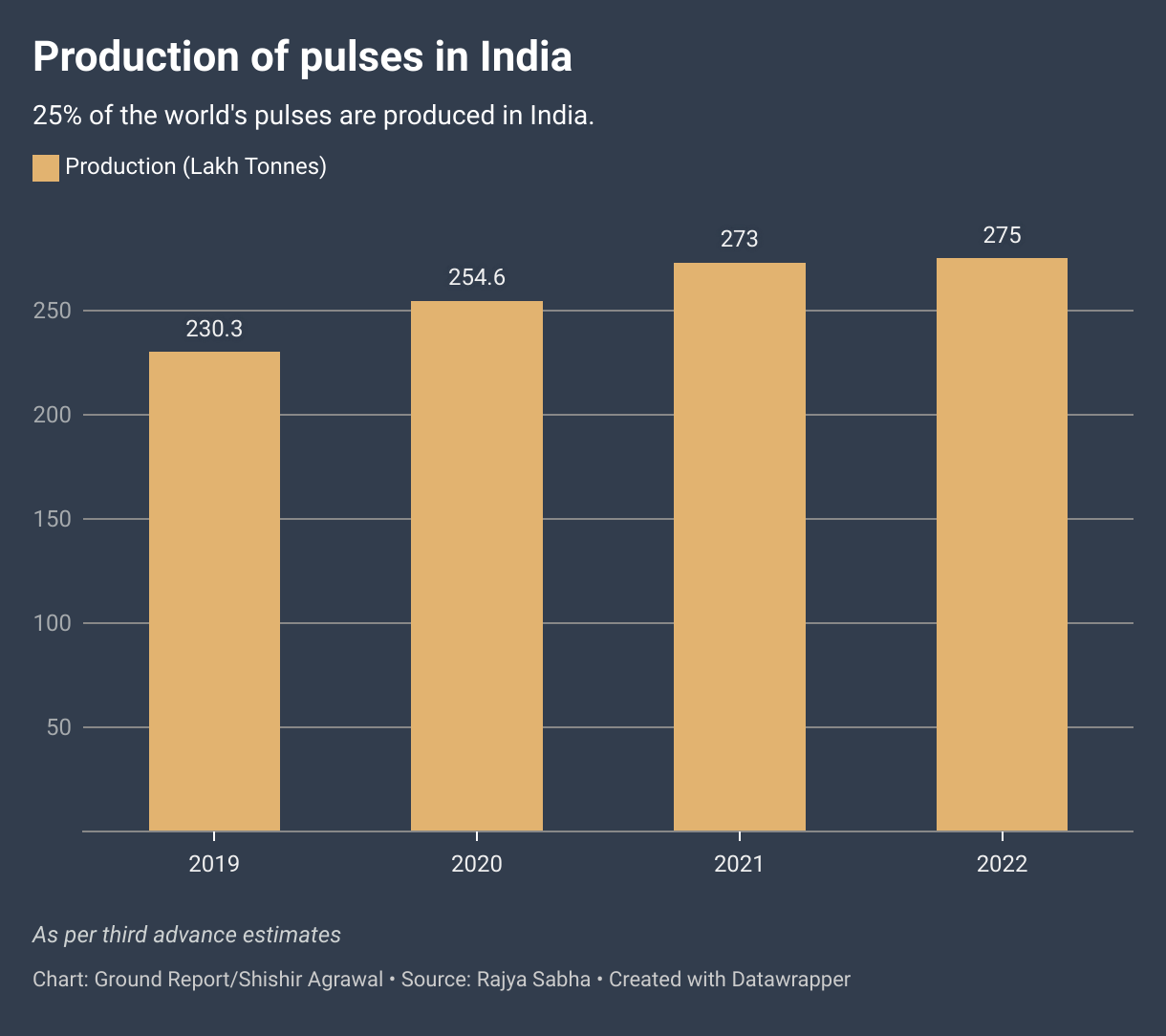

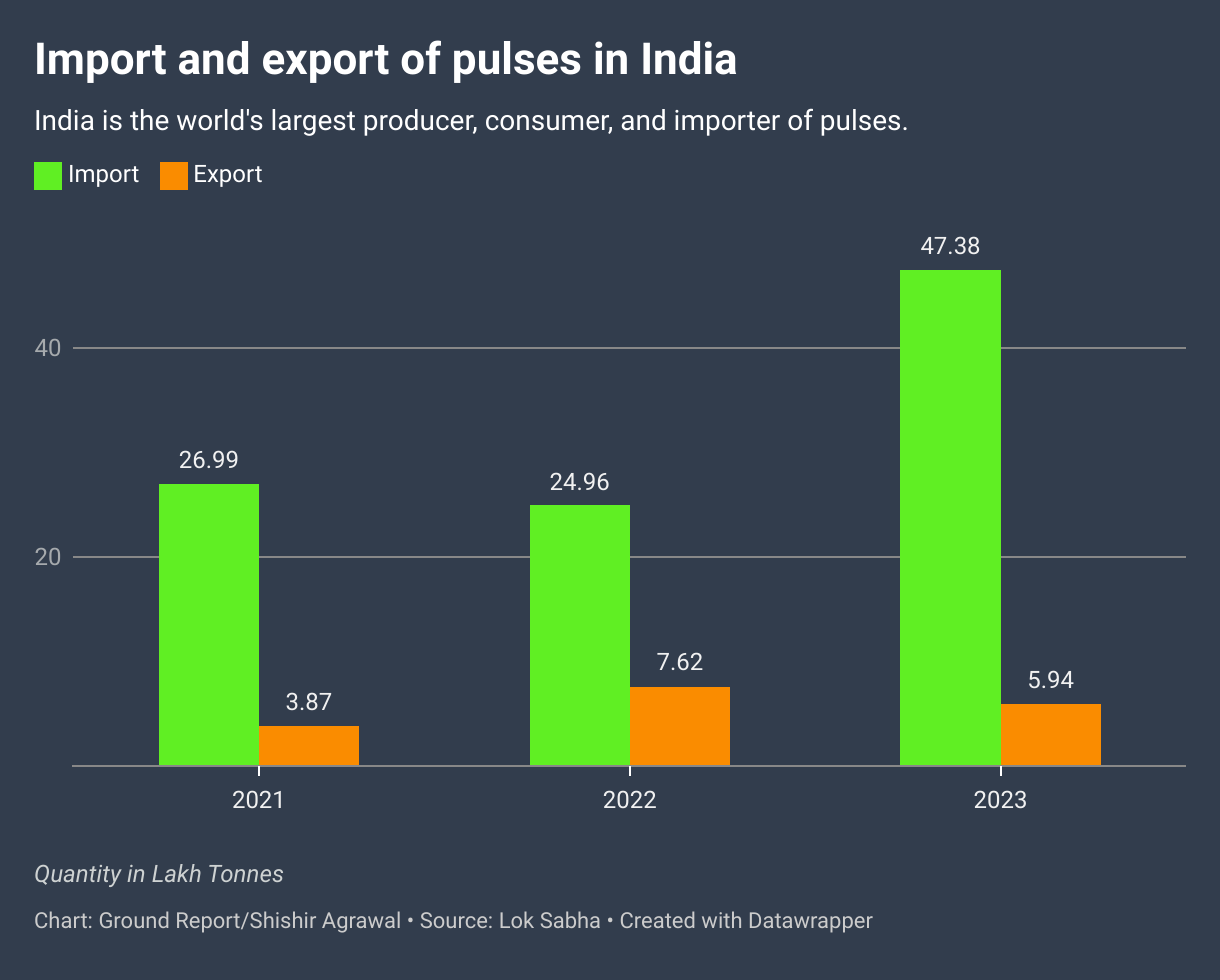

India is the world’s largest producer, consumer, and importer of pulses. 25% of the world’s pulses are produced here. At the same time, 27% of the world’s pulses are consumed in our country, and we import 14% of the world’s pulses.

Union Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Piyush Goyal claimed that the production of pulses has increased by 60 per cent in the last 10 years. This has reached 171 lakh metric tons in 2014 to 270 lakh metric tons in 2024. He said that the government has increased the procurement of pulses by 18 times in 10 years.

The National Food Security Mission (NFSM) was launched by the Central Government in October 2007. The objective of this mission was to increase the production of wheat, rice and pulses. NFSM-Pulse Mission was implemented in 644 districts of 28 states and 2 union territories. On July 30, 2024, Minister of State for Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Ram Nath Thakur, while replying in the House, said that the production of pulses in the country has increased between 2015 and 2023.

Thakur adds that the production of pulses in 2023-24 was 244.93 lakh tonnes. Whereas during 2015-16 it was 163.23 lakh tonnes. That is, in eight years, the total production has increased by only 81.7 lakh tonnes across the country. According to the government, the total production of pulses in India is sufficient to meet the domestic demand.

But according to the data from 2021 to 2023-24, the import of pulses in India has also increased. In the financial year 2023-24, it has doubled as compared to last year. Whereas in comparison, we are exporting pulses in small quantities.

In India, Tuar and Urad are mainly Kharif crops. On the other hand, lentil is considered a Rabi crop. According to the data from 2018 to 2022–23, the Tuar crop has been sown in an average of 45.55 lakh hectares. This has produced an average production of 38.11 lakh tonnes.

During this period, 17.66 lakh tonnes of Urad has been produced in 36.73 lakh hectares in the Kharif season. However, in the Rabi season also, Urad has been sown in 9.10 lakh hectares, which has produced an average production of 7.89 lakh tonnes. Whereas lentil cultivation has been done in 14.36 lakh hectares, which has produced 13.30 lakh tonnes.

Status of pulses in Madhya Pradesh

Under the National Food Security Mission, a total of 8,111.584 tonnes of pulses were produced in 7,480 hectares of Madhya Pradesh in 2024-25. At the same time, according to the data from 2014 to 2019, Madhya Pradesh has produced the highest amount of urad as compared to other states. During this period, this pulse crop was being cultivated in 14.65 lakh hectares of the state. This was producing 8.62 lakh tonnes of urad. Which is 33% of its total production across the country.

However the official website of the Farmer Welfare and Agricultural Development Department of Madhya Pradesh states that ‘the area of pulse crops is decreasing due to increase in the area of soybean in place of pulse crops in Madhya Pradesh.’

It is worth noting that in Madhya Pradesh, the area of soybeans has increased by 1.7% in 2023-24. In 2023-24, soybean was being cultivated in 6679 hectares in the state. Whereas in 2022-23, it was being cultivated in only 5975 hectares. However, according to the data from 2020 to 2023, the total production of pulse crops has increased in Madhya Pradesh. In 2020, this production was 4108.40 lakh tonnes, which reached 6270 lakh tonnes by 2023.

Troubled farmers

Wilt disease is a major concern for many pulse farmers in the state. Among them is 70-year-old Anokhilal Nagar from Obedullaganj in Raisen district, just 36 km from Bhopal. A farmer for 55 years, he currently cultivates nine acres of land. Previously, he also grew pigeon pea and lentils, but he was forced to stop due to recurring crop losses.

“Wilt disease made it impossible to continue growing these crops,” he says.

Take the example of Rajesh Nagar, a farmer from Gehunkheda village, another cultivator forced to abandon pulses due to crop diseases. Till eight years earlier, he grew lentils on his 13-acre farm but later switched to wheat and paddy.

“A decade ago, pulses were grown on 20-50 acres in my area. But over time, almost all farmers, including myself, stopped cultivating them,” he says. The reason–Ukhta disease.

Fusarium wilt or ukhta is a disease caused by a fungus called fusarium. It is visible only when the crop flowers. This disease occurs between September and January, in which the flower dries up and the roots rot and turn dark. This disease is considered to be the most destructive in lentil cultivation, which destroys the crop up to 100%. It can spread from one plant to the entire field and can also remain alive in the soil of the field as chlamydospore for many years, due to which it destroys the production in every crop cycle.

Talking about the disease, Dr Swapnil Dubey, head of Raisen Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK), says,

“Wilt is a soil-borne disease, and once it appears, the only solution is soil treatment,”

In a conversation with Ground Report. He explains that continuous cultivation of pulse crops makes the occurrence of this disease inevitable.

Farmer Anokhilal recalls that after repeated crop failures, he had his soil tested at Krishi Vigyan Kendra. Based on the results, he was advised to add zinc. Despite following the recommendation, the problem persisted, and no solution was found.

With a sense of frustration, Pawan Nagar another farmer from Obedullaganj says,

“Soil testing feels like a mere formality. Soil health cards are issued, but no one knows how to use them.”

Nagar too is unaware of the latest announcements in the Union Budget. When informed about the new mission for pulse crops, he responded that the government should first fulfill its past promises before making new ones.

He points out that the disease is now affecting gram crops as well. Rajesh Nagar shares his concern, saying that if no cure is found, farmers will eventually stop growing gram too. Regarding the budget announcements, he remarks that unless the disease is addressed, farmers won’t return to pulse cultivation—making these announcements meaningless for them.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Madhya Pradesh worst hit as India faces extreme weather on 322 days in 2024

On Ground: Plastic mulching boosts yield but harms soil health

Chhindwara’s maize-ethanol dream: promise vs reality

Erosion ravages Chambal: puts farmers, biodiversity at risk

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.