Walking through his farm in Samswara village of Chhindwara district on a bright January morning, Shishupal Singh Thakur beams with pride. He gives a tour of his lush maize fields. He shares his expectations for a bumper harvest of 35-40 quintals per acre this season. The recent addition of a bio-ethanol plant in the district further fuels his enthusiasm, promising good market rates for his maize crop.

As part of its journey toward achieving net-zero emissions by 2070, India is increasingly focusing on renewable energy alternatives, with bio-ethanol emerging as a key player in this green transition. This sustainable fuel, derived from plant sources like maize, sugarcane, and various grains, is produced through the fermentation of natural sugars and starches. Its versatility extends beyond transportation fuel, finding applications in pharmaceutical manufacturing, cosmetic production, and food processing.

What makes bio-ethanol particularly attractive is its dual benefit: not only does it serve as a renewable alternative to traditional gasoline when blended into biofuels, but it also generates significantly lower carbon dioxide emissions compared to fossil fuels. This environmentally conscious profile aligns perfectly with India’s ambitious climate goals, making it an invaluable tool in the nation’s strategy to combat climate change while reducing its dependence on conventional petroleum-based fuels.

Policy push for ethanol

In the process of making ethanol from maize, the top layer (husk) of maize is subjected to chemical processing in the plant. The peel is first broken down into sugars through a process called hydrolysis using enzymes or acids. Then sugar is mixed with yeast and fermented in ethanol.

The Government of India has also brought an ethanol policy on this in 2018. According to this, the central government has set a target of blending up to 20 percent ethanol in petrol by 2025. The Madhya Pradesh government has also taken the initiative to support this policy of the Government of India. The Madhya Pradesh government has also announced a number of subsidies aimed at increasing investment and setting up plants in the ethanol sector.

If ethanol plants give ethanol to oil marketing companies, then the state government gives Rs 1.50 per litre as production linked incentive. This includes a 100% waiver of stamp duty and registration fee for land purchase, a 5-year waiver of electricity duty, and a 100% reimbursement of patent fee. However, even after all these incentives, the number of ethanol plants in Madhya Pradesh is still limited.

Unsatisfactory prices unhappy farmers

Chhindwara, fondly called the ‘Corn City,’ has evolved into a year-round maize cultivation hub, with farmers successfully growing the crop in both Kharif and Rabi seasons. Former Madhya Pradesh Agriculture Department Director Dr. GS Kaushal highlights the progressive nature of Chhindwara’s farmers, noting their embrace of modern agricultural technologies and improved irrigation facilities—factors that contribute to exceptional Rabi maize yields.

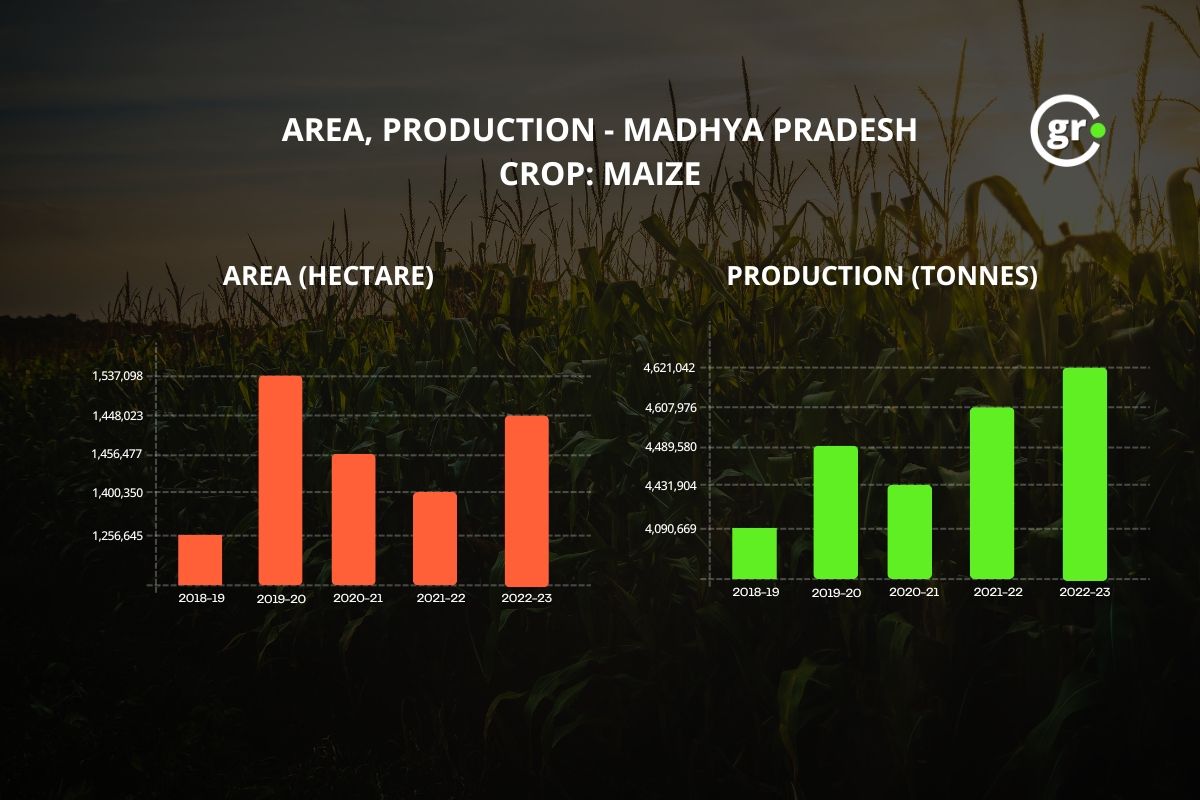

The state’s impressive maize production statistics support this agricultural success story. During 2022-23, Madhya Pradesh dedicated 1,448,023 hectares to maize cultivation, yielding 4,621,042 metric ttonnes—urpassing the previous year’s harvest by 13,066 MT.

While this robust production holds significant income potential for farmers, including revenue from both the primary crop and its byproducts, the economic reality is more complex than it appears at first glance. Despite the promising production figures and potential value of crop residues, Chhindwara’s farmers continue to face challenges in securing fair prices for their maize crop.

Shishupal’s agricultural journey reflects the evolving landscape of farming in his region. Until 2012, he dedicated his fields to soybean cultivation, relying entirely on agriculture for his family’s sustenance. However, declining soybean yields prompted him to transition to maize farming.

Yet, the challenges persisted in a different form. His Kharif season maize crops have struggled against unpredictable rainfall patterns and other adversities, yielding only 15-16 quintals per acre. This setback led to an adaptive strategy—Shishupal now harnesses his canal-adjacent 2-acre plot for Rabi season maize cultivation, where he anticipates a substantially higher yield of 40-45 quintals per acre.

Dissatisfied with the maize prices. Shishupal explains,

“When I had the largest stock of maize, I sold it at Rs. 2000 per quintal. Now, two months later, the same maize is priced at Rs. 2400 per quintal. It would have been better if we had received the same price earlier.”

The economics of maize cultivation weigh heavily on farmers like Shishupal, who invest Rs 20,000 per acre from planting to harvest. Currently, the crop residue—the husk—either serves as animal fodder or ends up being burned. While the upcoming ethanol plant in his city presents a potential opportunity, the procurement system leaves farmers feeling shortchanged.

“The ethanol companies don’t source directly from farmers,” Shishupal explains with frustration. “They operate through traders who manage the entire buying process. If these companies would purchase directly from us farmers, we could actually benefit from this opportunity.” His words highlight the gap between the promise of additional income from crop residue and the reality of a procurement system that may not fully serve farmers’ interests.

Limited ethanol plants

It is estimated that India produces more than 30 million tonnes of maize annually. About 14% of its weight is its husk. This means that about 4.5 million tonnes of ‘corn husk’ are available for industrial use. India’s industries consume about 1.5 million tonnes of corn husk annually for heating and energy production, but this is not even half of the total production of corn waste.

A 350 KLD (Kilo Litres Per Day) bio-ethanol plant has been set up at Borgaon under the Saunsar tehsil of Chhindwara. According to the project report, the plant will produce 350 kilo litres of bioethanol fuel, 245 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide, and 20 metric tonnes of corn oil per day. It will also generate 12 MW of power per day.

As a raw material, the plant will need 850 metric tonnes of starch-containing grains daily, including rice flakes, maize, millet, etc. At the same time, 1750 metric tonnes of water will be consumed daily to run this entire process.

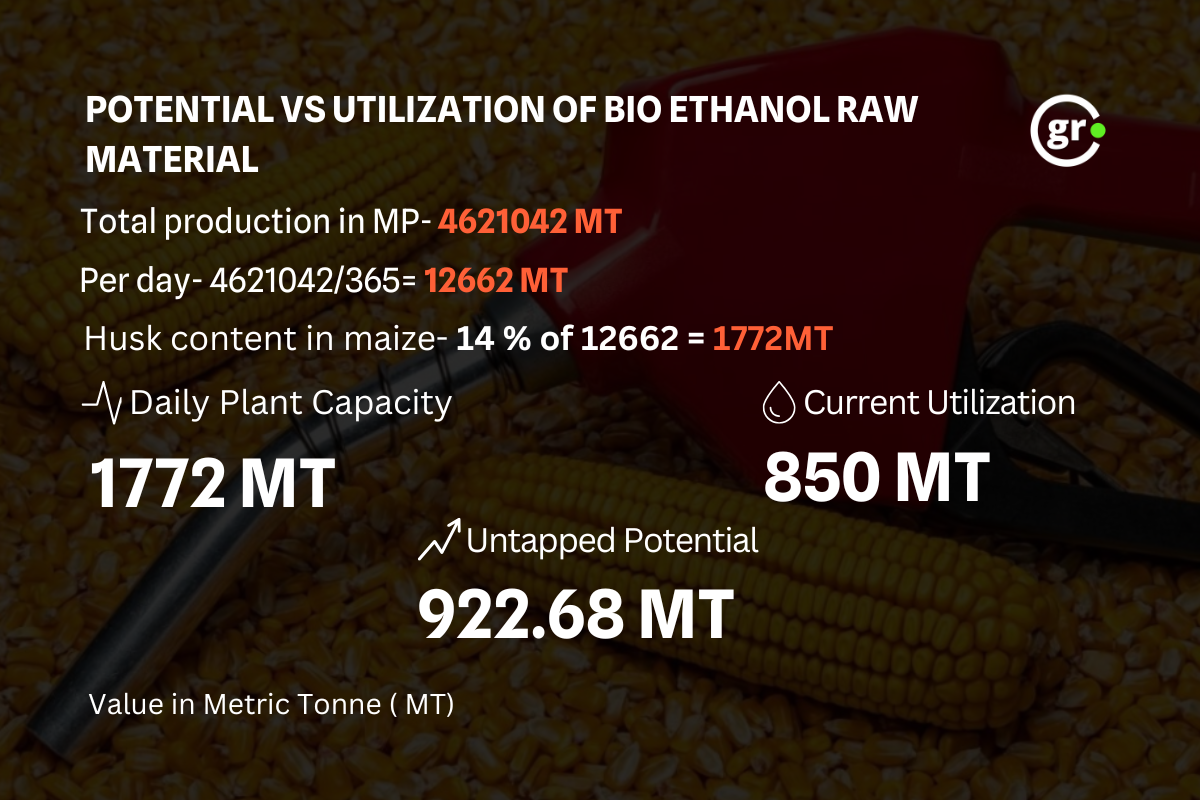

If the processing capacity of this one plant and the figures of the total annual maize production of Chhindwara itself are put in perspective, then both possibility and disappointment are seen. The math is simple. The total production of maize in Madhya Pradesh in 2022-23 was 4,621,042 MT, i.e., 12,662 MT maize per day.

Out of this total production, if the weight of 14% chaff is sorted separately, it is 1,772 metric tonnes At present, the plant takes only 850 tonnes of raw material per day. That is, even after the ethanol plant, 922.68 metric tons of maize husk remains untreated.

The Government of India has set a target of 20% ethanol in petrol by 2025, but so far we are able to blend only 16% ethanol. To achieve a 20% ethanol blending target by 2025, the estimated requirement of ethanol is 1016 crore litres. For other industrial uses, 334 crore litres of ethanol will be required. Thus, the total ethanol requirement in the country is estimated to be 1350 crore litres in 2025 for fuel blending and other uses.

The gap between India’s ethanol ambitions and current reality is stark: while the target calls for 1700 crore litres of production capacity by 2025 (to achieve 1350 crore litres of actual output at 80% capacity utilization), Union Minister Suresh Gopi’s Lok Sabha statement reveals the present capacity stands at merely 500 crore litres – significantly short of the goal.

Drawing from his experience with soybean’s declining yields, Shishupal shared with Ground Report his concerns about a similar fate potentially awaiting maize cultivation in Chhindwara. His worry raises a critical question: would establishing ethanol plants after maize production reaches its saturation point in the region serve any purpose? This situation underscores the urgency of not only expediting the establishment of these plants but also restructuring the procurement system to enable direct farmer participation, bypassing middlemen (arhtiyas), to effectively meet India’s green energy targets.

Edited by Diwash Gahatraj

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

California Fires Live updates: destructive wildfires in history

Hollywood Hills burning video is fake and AI generated

Devastating wildfire in California: wind, dry conditions to blame?

Los Angeles Cracks Under Water Pressure

From tourist paradise to waste wasteland: Sindh River Cry for help

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.