Nilbad is a village located 13 km from Ichhawar tehsil in Sehore district. As you pass through the village, you can see chickpea crops being harvested in the fields on both sides of the road. Elderly villagers sitting at the chaupal near the village entrance shared that while this year’s wheat crop, which will be harvested in March, appears to have a good yield, most farmers have suffered significant losses with their chickpea crops.

One of the elderly in the group, 62-year-old Karan Singh, wearing a white dhoti and kurta, says, “We had planted a Turky variety of chickpea on 4 acres of land, which has been completely destroyed. The plants have pods but there is no grain inside.“

Singh is unsure about the reason behind the crop damage. He says,

“Only God knows why this happened. The weather was good this time. Maybe some disease affected the crop.”

Sitting beside him, another farmer, Dilip Singh, shares a similar concern.

“The soil here has become unhealthy. Every year, our crops suffer from some disease or the other. We’ve even had our soil tested, but we haven’t received the report yet. If we knew what nutrients were lacking, we could have addressed the issue. For now, we’re applying fertilisers and pesticides based on guesswork.”

The Government of India started the Soil Health Card Scheme in the year 2015 to solve the problems of farmers like Dilip.

What is a soil health card?

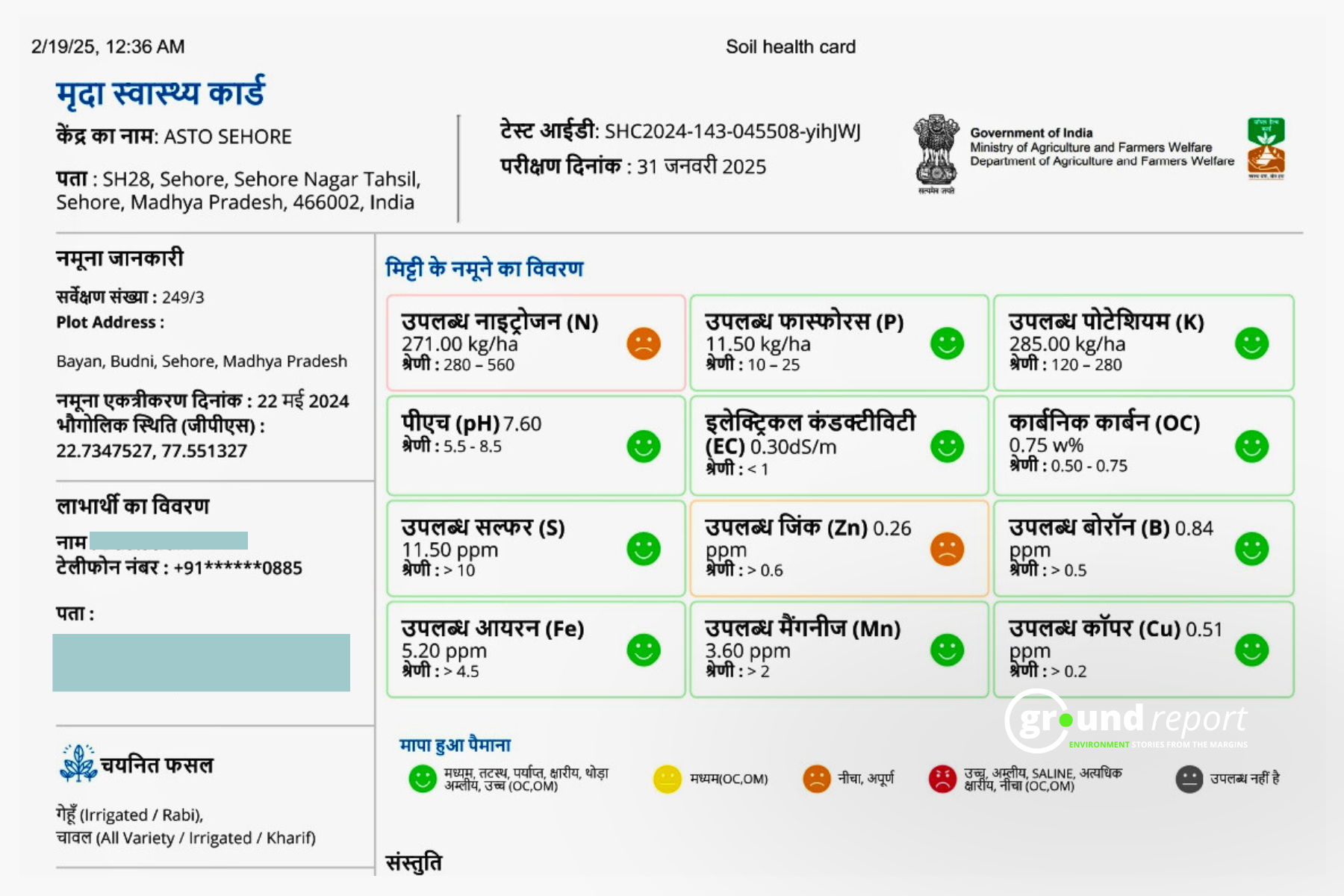

A soil health card is a printed document showing the soil condition of the farmer’s field according to 12 parameters. Such as macronutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium), secondary nutrients (sulphur), micronutrients (zinc, iron, calcium, magnesium, boron), and physical parameters such as pH, electrical conductivity and the amount of organic carbon in the soil and what should be the standard. With its help, farmers can get better yields by knowing the health of their soil and choosing the right crops and fertilisers.

According to the information given by Minister of State for Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Ram Nath Thakur in a written reply in the Lok Sabha on 4 February 2025, so far 24.74 crore Soil Health Cards (SHC) have been generated across the country and an amount of ₹ 1706.18 crore has been released to various states/union territories for this work.

8272 soil testing labs have been set up across the country with the money given by the government. However, there is only one soil testing laboratory in Sehore district, which has the responsibility of testing soil samples from all five blocks of the district. Sehore District Agriculture Deputy Director K.K. Pandey says,

“Four mini-labs are being built at the block level, where sample collection facilities will be available. This will not increase the testing capacity of the district, but the work of sample collection will be divided.”

Condition of soil testing lab

When we visited the soil testing laboratory in Sehore, we found cupboards filled with soil samples collected from farmers’ fields, each labelled with a slip bearing the farmer’s name. The laboratory housed various machines used to analyse the nutrient composition of the soil.

Kiran Bhalla, who works here, is entering the results after testing the soil on the Soil Health Card dashboard. She says that

“this work has to be done very responsibly and it also takes a lot of time.”

Bhalla shares that for the year 2024-25, she has been assigned a target of testing 20,000 soil samples. With two months remaining, she has tested 13,926 samples so far.

“The machines in the lab can test 55 samples at a time, and it takes about a week to complete the analysis for each batch. Once the testing is done, a Soil Health Card is issued, which farmers can download online,” she explains.

Understanding the slow process of soil testing and the district administration’s limited resources, the concerns of farmers like Dilip, who are still waiting for their Soil Health Cards, seem justified.

However, Bhalla clarifies,

“If a farmer personally submits their soil sample for testing, the report is provided within a week. But very few farmers take the initiative to get their soil tested themselves.”

Our field investigation revealed the lack of awareness about soil health cards among farmers. Many farmers in Chhindwara, Sehore and Bhopal districts did not know how and where to get their soil tested. Also, the farmers who themselves submitted their soil samples to the government allege that they have not yet received the report.

Shishupal Thakur, a farmer from Chhindwara, complains,

“I had given my soil sample to the officials, a year ago. Despite multiple visits to the agriculture department, I have not got the report yet.”

According to the Soil Health Card Scheme, a farmer has to get his soil tested every three years. For this, he will have to submit the soil sample of his field to the nearest lab and receive the card after the test is completed. In such a situation, the question arises that 10 years after the launch of this scheme, when the soil of all the farmers’ fields has not been tested yet, how will it be possible to repeat this process every three years for an individual farmer?

How important is a soil health card?

Dr. S.C. Gupta, Principal Scientist in the Department of Soil Science at Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Agricultural College, Sehore, has been observing the trend of lack of organic carbon and micronutrients in the soil of the Sehore region for the last few years. He says,

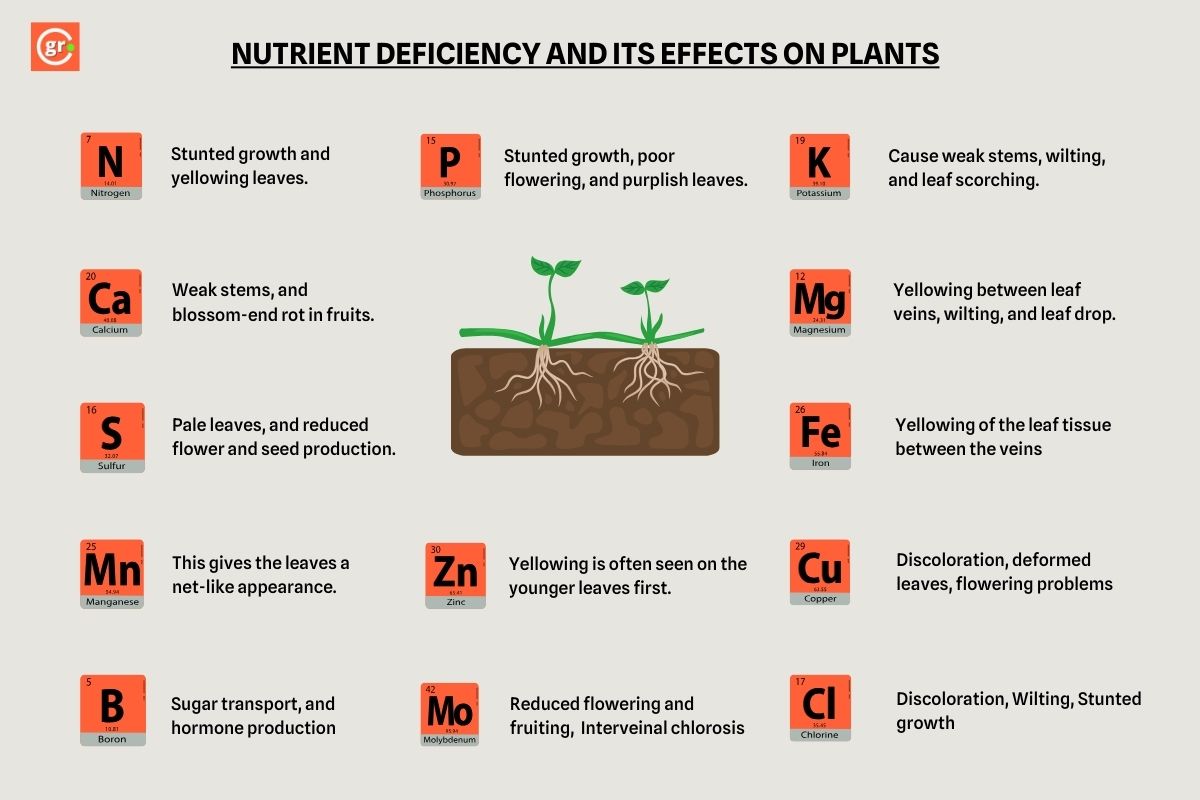

“When there is a lack of these elements in the soil, it directly affects the health of the crop. By finding this out through soil testing, the farmer can compensate for that nutrient. In such a situation, a soil health card becomes necessary. However, their effectiveness depends entirely on farmers understanding the information and implementing the recommended practices.”

When Ground Report asked agrochemical traders near Sehore Upaj Mandi whether farmers purchase these inputs based on their Soil Health Cards, they responded,

“We have never seen a farmer bring a Soil Health Card. Most farmers have memorised the names of certain fertilisers and pesticides, which they buy every year. They simply describe the issue affecting their crops and ask for a suitable remedy.”

In India, farmers rely on shopkeepers and agrochemical company agents for advice on fertilisers and pesticides, much like people who self-medicate by describing symptoms to a pharmacist. It’s akin to treating a fever without realising the underlying illness is malaria.

Dr. M Yasin, Dean at Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Agricultural College and a scientist, asks us, “Have you seen agro clinics anywhere in India? … You may not have seen them because in India there is no seriousness about knowing the health of crops and soil.”

Just one gram can change the results

Dr. S.C. Gupta shares his experiment, which highlights the importance of soil testing. He analysed soil samples from the Sehore Agricultural College farm. He discovered that molybdenum levels had declined due to the continuous soybean-gram and soybean-wheat cropping patterns over the past 4-5 decades.

To address this deficiency, he planted chickpea crops using Rhizobium+PSB inoculated seeds and treated them with ammonium molybdate at 1 g/kg seed in one section of the field, while leaving the other untreated. The results showed a significant difference—fields where molybdenum was supplemented saw a yield increase of about 25%.

This experiment underscores the value of soil testing. Identifying micronutrient deficiencies allows farmers to improve yields with precise supplementation, rather than unknowingly applying large amounts of fertilisers like urea and DAP in an attempt to fix the problem.

Phool Singh, son of farmer Karan Singh from Nilbad, displays pods from his recently harvested chickpea field. As he cracks them open one by one, it becomes evident that most are empty, and the few grains present are visibly damaged. Karan expresses frustration, desperately wanting to understand what destroyed his crop and how to prevent such losses in the future.

Unfortunately, his desire for answers faces a significant roadblock. While India’s agricultural markets overflow with remedies for crop diseases, diagnostic services to accurately identify these ailments remain scarce. Soil testing—the fundamental first step in agricultural problem-solving—is often overlooked. There’s an urgent need to educate farmers about its critical importance. For real change to occur, regulations must prohibit the sale of fertilisers and seeds without reference to Soil Health Cards. Without such measures, these potentially valuable tools will remain just pieces of paper destined for the waste bin.

Dr. M. Yasin illustrates this predicament with a pointed comparison: “In the United States, even basic medications like paracetamol require a doctor’s prescription. Meanwhile, in India, untrained individuals often dispense medicines directly to patients without proper diagnosis.” He concludes,

“When we haven’t yet prioritized human health properly, the road to valuing soil health will be significantly longer and more difficult.”

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Mission aatmanirbharta in pulses: MP farmers remain skeptical

On Ground: Plastic mulching boosts yield but harms soil health

Chhindwara’s maize-ethanol dream: promise vs reality

Erosion ravages Chambal: puts farmers, biodiversity at risk

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.