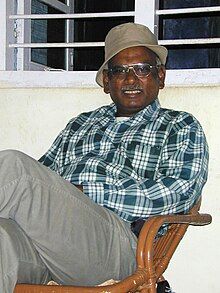

A.J.T. Johnsingh, a celebrated wildlife biologist and conservation advocate, died at 78 in Bengaluru after a brief illness. His passing is a loss for India’s environmental movement and the global fight to protect biodiversity.

Who was A.J.T. Johnsingh?

Johnsingh was born in 1946 in Nanguneri, Tamil Nadu. Family excursions ignited his passion for nature to the future Kalakkad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve. His parents, and educators, nurtured his curiosity about the natural world through agriculture and tree planting.

After Johnsingh got his master’s in zoology from Madras Christian College, he briefly worked as a lecturer at Ayya Nadar Janaki Ammal College in Sivakasi. However, his true calling was in the field studying India’s diverse wildlife firsthand. His research on dholes (Asiatic wild dogs) in Bandipur Tiger Reserve in the 1970s, including a harrowing close encounter with a charging tiger, brought him international recognition as one of the first Indian scientists to study free-ranging mammals.

This experience set the stage for a lifetime dedicated to understanding iconic Indian species like the Asian elephant, Asiatic lion, Nilgiri tahr, sloth bear, and various deer and primates. Johnsingh authored over 70 scientific papers and 80 popular articles, inspired by naturalist George Schaller.

Mentored India’s next conservation leaders

In 1981, Johnsingh returned from the Smithsonian Institution to join the Bombay Natural History Society before becoming a founding faculty member at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in Dehradun. There, he expanded the institute’s scope and served as Dean, mentoring generations of India’s forest managers, wildlife biologists and conservationists.

P.O. Nameer, a former student now Dean at the College of Climate Change and Environmental Science in Kerala, said, “He was India’s top vertebrate ecologist. His contributions to wildlife biology and conservation in this country are manifold. He knew many tiger habitats intimately.”

Johnsingh’s efforts were crucial in establishing several tiger reserves across India, notably KMTR which protects a vast stretch of the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot. His fieldwork pioneered research on endangered species from the golden mahseer to the grizzled giant squirrel.

“AJT was a native of this region who inherited his passion for wildlife from his father and became an expert naturalist,” said Albert Rajendran, Johnsingh’s professor at St. John’s College in Palayamkottai. “I learned a lot from him in the field. His down-to-earth attitude and approach to conservation is well known.”

What set Johnsingh apart was his courage to speak truth to power for the voiceless creatures. He was a scientific professional with the conviction to call out wrongdoing, malfeasance, and apathy.

Exposed Sariska tiger poaching crisis

Johnsingh played a key role in exposing the disappearance of tigers from Sariska Tiger Reserve due to rampant poaching in the mid-2000s. His testimony was crucial in officially designating the reserve as devoid of tigers, sparking a major conservation crisis and eventual reintroduction efforts.

He was outspoken about human-animal conflicts, advocating scientific, humane protocols in places like the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve rather than cruel retaliation. Johnsingh recognized that conservation required practical concessions. He suggested to sustainably harvest dead teak trees debarked by elephants to fund village resettlement.

“I sincerely desire that we have persuaded influential individuals, especially politicians, to support wildlife preservation,” Johnsingh said in an interview about conservation in India. “But slow progress is a defining feature of our country.”

Johnsingh remained optimistic about India’s environmental future despite frustrations with bureaucracy and political inaction. In his later years, he emphasized mentoring youth and urging the next generation to stay curious, study nature directly, and collaborate across ideological lines.

“Nature is a great teacher. Follow your curiosity,” he advised aspiring conservationists. “Learn to work with authorities and persuade them to take actions that protect Nature.”

Honored with numerous conservation awards

Johnsingh was showered with prestigious accolades including the Padma Shri, the Society for Conservation Biology’s Distinguished Service Award, the Carl Zeiss Wildlife Conservation Award, and the ABN AMRO Sanctuary Lifetime Wildlife Service Award.

Johnsingh’s conservation ethic represents a timeless model for protecting India’s natural heritage. It is a passion tempered by scientific pragmatism and an ability to inspire across generations.

His family said in a statement, ‘We can’t hear his voice, but we hear him in the chirp of every bird, roar of every tiger, and trumpet of every tusker. Generous and unmatched as a teacher, he leaves behind a conservation legacy.'”

As news of his passing spread across the conservation community, many mourned the loss of a towering figure and irreplaceable folk hero of the Indian environmental movement. In the days ahead, a nation will bid farewell to one of its most fearless champions for preserving nature.

Johnsingh will be buried next to his late wife Kousalya at Dohnavur near the Kalakkad region of the Western Ghats. It’s a fitting resting place for a man who drew inspiration from those landscapes and devoted his life to ensuring their protection.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

bioDon’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.