A recent study has revealed a troubling gender gap in India concerning the impact of extreme heat, revealing that women are considerably more vulnerable to such conditions than men. Since 2005, there has been a worrying surge in heat-related fatalities among women in the country, as per an analysis published in Significance Magazine, a journal by the Royal Statistical Society.

Ground Report interviewed Ramit Debnath, a university assistant professor and an academic director at the University of Cambridge, and one of the authors of the study. He emphasized the findings, stating,

“We find through descriptive statistical analysis that publicly available data for India shows that females exhibit a heightened susceptibility to extreme temperature conditions (specifically heat) compared to males.”

To bridge this gap, the team relied on 30 years of data on extreme temperature-related mortality, extracting information from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database, which offers annual estimates for gender-specific temperature-related mortality rates in India. Despite the insights gained from the GBD, the data lacked granularity.

Additionally, the team collected India’s daily temperature data from 1990 to 2019 recorded by the India Meteorological Department (IMD). Their analysis revealed contrasting trends between men and women in terms of temperature-related mortality.

The analysis revealed gender disparities in temperature-related mortality. While men saw mortality rates decline over time, women experienced a gradual increase, particularly from 2005 onwards. From 2000 to 2010, men’s mortality rates decreased by 23.11%, and by 18.7% from 2010 to 2019. In contrast, women’s mortality rates increased by 4.63% from 2000 to 2010 and 9.84% from 2010 to 2019.

Out of the 16 studies examined, four originated from India. Among these, three indicated that women are at a heightened risk, while one suggested otherwise. The researchers observed that studies in the Global South offer differing perspectives on gender-specific mortality rates related to temperature changes, reflecting conflicting findings.

Q: Can you elaborate on the factors contributing to the heightened vulnerability of women to extreme temperatures in India, as highlighted in your study?

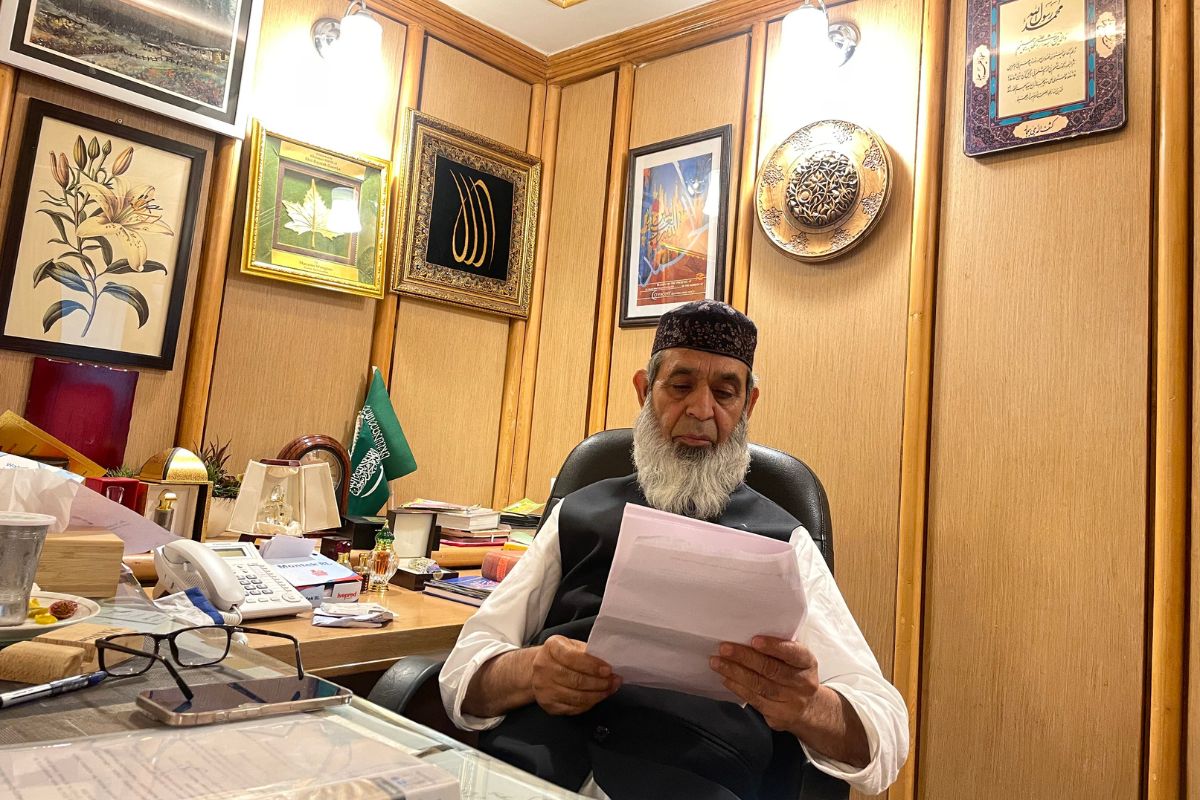

A: Factors include a complex mix of socio-economic and physiological factors. Socio-economically, women in lower-income communities have fewer cooling and adaptation agencies to cope with extreme heat which can be due to expensive cooling devices like ACs, poor design of homes that restricts cross-ventilation or active air exchanges or even poor quality materials that let heat pass through easily and get it trapped inside homes. Moreover, there are heavy burden of household work, including fetching drinking water and firewood (especially in rural areas), etc. Physiological factors associated with menstruation, pregnancy and lactation put them at higher vulnerability.

Photo Credit: Ground Report | A woman in Aadampur Village Near Bhopal, lives in a Tin Roof house, showing how mosquito bites and heat cause skin infection to her child.

Q: What do you believe are the primary reasons behind the gradual increase in temperature-related fatalities among women since 2005, as indicated by your analysis?

A: The gradual increase in temperature-related fatalities among women in India since 2005, as revealed by recent analysis, raises concerns over gender disparities in coping with extreme heat. While improved reporting of female mortality suggests heightened awareness, advancements in public healthcare infrastructure and socioeconomic conditions may have disproportionately benefited men. Women, facing rigid cultural norms and spending more time indoors, are particularly vulnerable due to poor ventilation and cooling facilities.

Q: Could you discuss any potential implications of the rigid cultural norms and societal expectations faced by women in the Global South on their ability to respond and cope with extreme temperature risks?

A: We highlight one aspect of skewed labour force participation of the female gender that states that women are 54% more likely to stay indoors than men. Poor quality of housing design and material use could make heatwave impact worse in such buildings that affect who spends most time indoors. Moreover, especially in rural and low-resource settings, women have additional sociocultural burdens of fetching drinking water and fuel for cooking often by travelling at larger distances and this pattern holds true for most of the Global South. This makes them more exposed to the high temperatures during the daytime.

Photo Credit: Ground Report | A woman in Samasgarh village of Madhya Pradesh making tea on wood-fired chulha for a family in the scorching heat of summer.

Q: How does the absence of data on indoor populations affect our understanding of gender-specific vulnerability to extreme temperatures?

A: This is an important missing data as without this we could estimate with certainty whether the gender-specific trends have changed on who stays indoors more and how to design interventions for those who are indoors as well as outdoors. Also, the absence of such data prevents us from fully comprehending how indoor conditions, such as poor ventilation and cooling facilities, exacerbate women’s vulnerability to extreme temperatures. Addressing this gap is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate heat-related health risks, especially for marginalized communities.

Q: How can we improve datasets to capture volatile changes in mortality and extreme temperatures more effectively?

A: The optimal dataset would include information on daily trends (if not hourly), cause of mortality, information on temperature and humidity at an hourly level as well as basic demographic information that sheds light on the socio-economic contexts. Similarly, spatial data at the hyper-local level could be very helpful.

Q: Could you expand on the potential impacts of long-term factors such as advances in healthcare or changes in population demographics on temperature-related mortality rates in India?

A: One example that I witnessed two days back in Kolkata heatwave is my phone started to beep with extreme weather warming stating high temperature and potential immediate mitigation measures like seeking shaded areas, drinking water, covering the head with white clothes, etc. This is an important information-led intervention at the population level from IMD, but it is only limited to those who have smartphones and can interpret this message. I think it’s an excellent step by the government, but we have to also think from a public health planning perspective on how to identify risky zones at local or even hyper-local levels and place supporting infrastructures, etc. India’s heat action plan is evolving to great lengths and to make it even more effective we would need such spatial information at a much granular level.

Q: How do you think the findings of your study could inform policy decisions or interventions aimed at mitigating the gender disparity in coping with extreme heat in India?

A: Our study at this stage is observational and one key message is we need to rethink what is good quality and actionable data from the ground. This calls for setting up appropriate data infrastructure not just at the Indian level but at every high-heatwave vulnerability nation. This would need a collective partnership-based effort.

Q: What more research is needed to understand why women are more vulnerable to extreme heat in the Global South, particularly in places like India?

A: One important avenue of research is to get a grounded qualitative insight into the lived experiences of heatwaves at a gender-specific scale. Such stories could help us understand what is the most pressing questions related to heatwaves. Similarly, there is a need to emphasize that technosolutionism is not the ultimate answer to this problem, while low-cost materials and ACs could serve the purpose at an immediate scale we need to engage with behavioural change that can build heat resilience.

Q: Are there any particular challenges or limitations encountered during your analysis that you believe warrant further investigation or consideration?

A: One limitation is due to a lack of data we could not perform causal analysis, we reported observational findings. We could not figure out why gender-specific mortality data was behaving in a current way, we just have an intuition for what might have happened. And intuitions cannot design effective policy action.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.