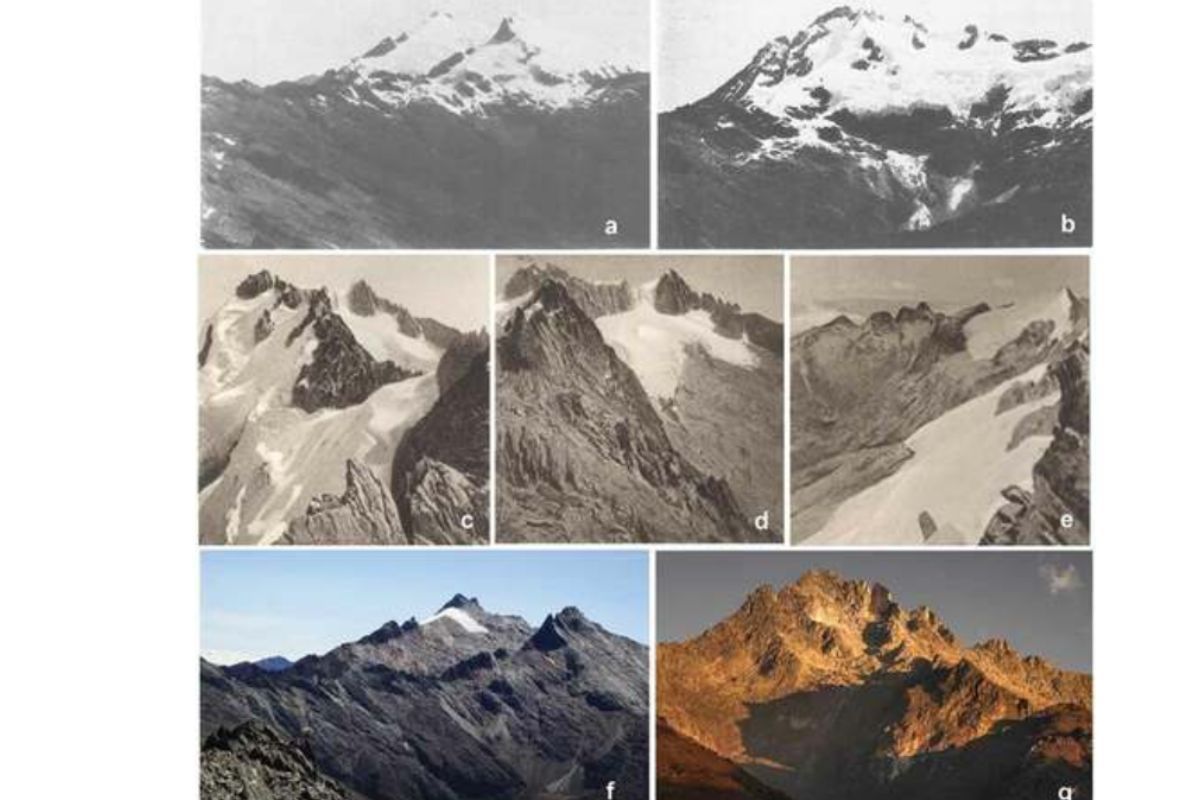

The Humboldt Glacier, also known as La Corona, once Venezuela’s last glacier, has diminished to the extent that it’s now classified as merely an ice field. According to the criteria, glaciers must cover a minimum of 10 hectares to retain their status. Originally, Venezuela boasted six glaciers spanning a collective area of 1,000 square kilometres. La Corona alone encompassed 450 hectares. However, today, it has dwindled to just two hectares.

Earlier in May 2024, reports confirmed that the La Corona glacier had shrunk to the point of no longer meeting the criteria to be classified as a glacier. This significant reduction in ice volume is attributed to rising global temperatures driven by climate change and global warming, as evidenced by previous data. Venezuela’s loss of its last glacier potentially marks a historic moment, positioning the nation as one of the first in modern human history to lose all its glaciers.

The disappearance or shrinking of glaciers outside Antarctica is not unprecedented. In China, thousands of glaciers have melted over recent decades, according to previous estimates. Similarly, in Greenland, scientists have observed an accelerated rate of ice melt, a consequence of the climate crisis. Meanwhile, in Chile’s Patagonia region, glaciers are also experiencing similar phenomena.

Last Glacier of Venezuela

Venezuela has officially lost its status as a glacier-bearing nation after its final glacier, La Corona on Humboldt Peak, melted away. Situated at an altitude of 4,900 meters, the remaining Humboldt Glacier dwindled to just 2 hectares in size, rendering it too small to qualify as a glacier. This revelation, detailed in a report by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, positions Venezuela as not only the first country in the Andes Mountain range but also globally, to lose all its glaciers.

According to a report shared on platform X (previously Twitter), Indonesia, Mexico, and Slovenia are the next countries on track to lose their glaciers. These developments underscore a trend observed over the past century, wherein glaciers worldwide have experienced significant melting.

Experts had predicted that the Humboldt Glacier would persist for approximately another decade. However, political unrest in Venezuela hindered scientists from monitoring the site for several years, as reported by The Guardian. Consequently, Venezuela has become the first Andean country to lose all its glaciers.

“There hasn’t been this much ice cover on the last Venezuelan glacier since the 2000s,” said Caroline Clason, a glaciologist at Durham University. “Now it is not being expanded, so it has been reclassified as an ice field.”

Luis Daniel Llambi, an ecologist at this university, told “The Guardian” that now even less than two hectares remain.

In December 2023, the government took steps to safeguard the remaining glaciers by implementing a “thermal cover.” This protective measure aims to decelerate the melting process. Typically composed of layers of plastic and fleece-like material, these covers function by insulating against solar radiation while permitting water infiltration, Scientific American reports.

Alejandra Melfo is involved in the “The Last Glacier in Venezuela” project, which aims to examine the glacier’s retreat and the emergence of a new ecosystem. Supported by the National Geographic Society, the University of Los Andes, the National Observatory against Climate Change, and other international partners, the project explores the unprecedented use of thermal blankets on tropical glaciers lacking distinct seasons. Melfo highlighted the novelty and uncertainty of this approach in an interview with The Country.

However, environmental activists have voiced concerns about the potential negative impacts of the government’s plan. They fear that the decomposition of the plastic materials used in the thermal blankets could release microplastics, harming the delicate ecosystem by contaminating water and air. One activist expressed reservations about the environmental costs associated with transporting and depositing three tons of plastic materials in such a sensitive environment in a statement to CNN.

Glacier Melt and Climate Change

Glacier melt poses severe environmental consequences, including its role in elevating sea levels globally. According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), scientists have observed changes in snow cover, permafrost, glacier melt, and precipitation extremes over the years.

In a case study focusing on the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region, encompassing nations like Bhutan and Nepal, the UNFCCC revealed alarming trends. Between 1980 and 2010, Bhutan experienced a loss of about 23% of its glaciers, while Nepal, home to Mount Everest, saw a reduction of 25% in its glacier coverage. These findings were presented by the UN agency in April 2023.

Scientists attribute the significant glacier melts outside polar regions to anthropogenic climate change. This phenomenon is fueled by greenhouse gas emissions and the burning of fossil fuels across various industrial and societal sectors.

While there is no global standard for how big an ice mass must be to be classified as a glacier, the United States Geological Survey says a widely accepted figure is 10 hectares.

A study, published in 2020, suggested that the glacier shrank to less than that sometime between 2015 and 2016, although NASA still considered it in 2018 to be Venezuela’s last glacier.

“It is a remnant of ice,” says ULA physicist Alejandra Melfo, associate researcher of the Último Glaciar project, who returned in December 2023 after four years without climbing the peak. “It’s very small,” describes Melfo, who studies new ways of life in the place.

The disappearance of the glacier will also affect mountain tourism since the majority climbed Humboldt via the glacier, indicates forestry engineer and mountaineer Susana Rodríguez.

“Now everything is rock, and what remains is so deteriorated that it is risky to step on it, there are cracks,” he laments. “Will this be the last time we saw him?”, she wonders.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.