A study suggests climate breakdown could trigger widespread migration of venomous snakes into new regions and unprepared countries. Researchers examined snake species and habitat lists, revealing patterns indicating a shift in their distribution towards unprepared areas. An international team warns that if global temperatures rise by 5 degrees Celsius, there could be a substantial influx of venomous reptiles into various regions.

Recent research suggests that venomous snakes may migrate to other countries for better habitats due to climate change. This migration poses risks to unprepared nations, potentially leading to more snake bites. India is vulnerable to this threat.

An international research team, led by Professor Pablo Ariel Martinez of the Federal University of Sergipe, studied data on 209 venomous snake species worldwide. The study, published in Lancet Planetary Health, examined these known to endanger humans and constructed a model mapping their geographical distribution.

“Martinez said, ‘Climate change is expected to have profound effects over the years, such as the loss of biodiversity and changes in poisoning patterns for humans and domestic animals.”

ALSO READ: April 2024: Another Record-Breaking Month for Global Heat

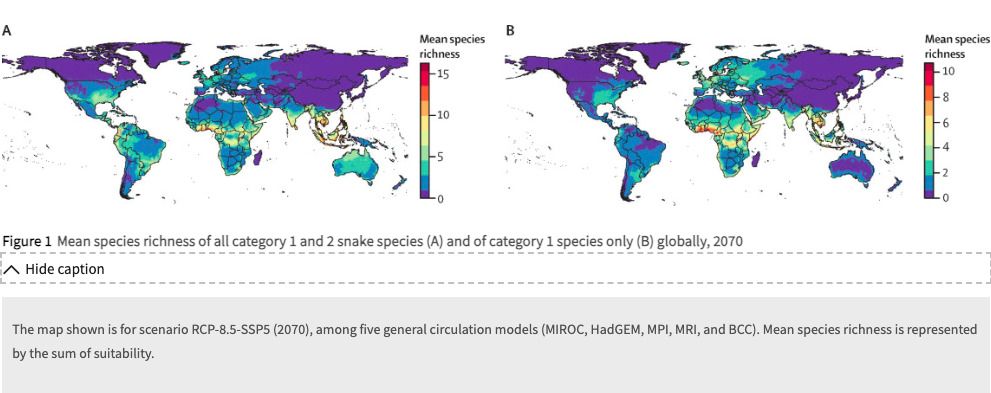

Researchers projected snake migration patterns by 2070 due to increasing temperatures and shifting climates using this model. The study suggests that many venomous snake species may lose their habitats within the next 46 years. Conversely, certain species posing risks to human life may adapt to new environments.

India, Nepal, Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, Thailand: Threatened

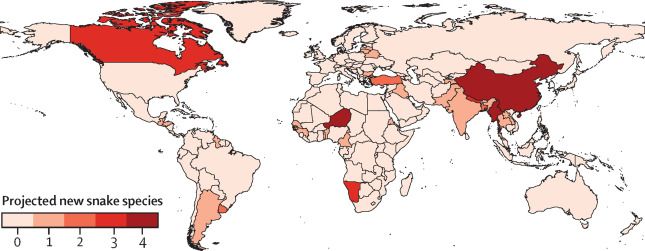

According to the study, there are concerns about an increase in venomous snake species migrating to countries like Niger, Namibia, China, Nepal, and Myanmar from neighbouring regions.

The research suggests that in the future, South and Southeast Asia, and Africa could experience a rise in snake bites due to expanding suitable habitats for snakes, driven by climate change and socioeconomic factors like poverty and population growth. This may especially affect countries like India, Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Thailand, increasing pressure on their healthcare systems.

Many venomous snake species are losing habitat as tropical and subtropical ecosystems decline. The study highlights exceptions, such as the West African gaboon viper, which could see its habitat expand by up to 250%. Projections suggest that the ranges of the European asp and the horned viper may more than double by 2070. Conversely, species like the variable bush viper in Africa and the hog-nosed pit in the Americas are expected to lose over 70% of their habitat.

ALSO READ: Concerns raised over Green Credit rules by environmental groups

Access to antivenom is limited in areas with new snake species, and habitat changes could increase animal bites, causing socio-economic challenges.

The most significant decline in venomous snake species is expected in South America and Southern Africa by 2070. There is a risk of habitat damage in these areas, compounded by climate change, potentially affecting biodiversity.

Snake habitats shifting, species diversity changing

Most venomous snakes are expected to suffer habitat loss, especially in tropical and subtropical regions rich in snake biodiversity. However, species like the West African Gabonese viper may see increases of up to 251 percent. The habitat of Vipera aspis in southwestern Europe could expand by 136 percent, while the horned viper species may experience a 118 percent range increase by 2070.

Several bush viper species, including Atheris squamigera, Rock Viper, Field’s Horned Viper, American Hognosed Pitviper, Bothrops brazili, and Protobothrops elegans, face habitat reductions exceeding 70 percent.

Researchers project that areas reliant on intensive agriculture and livestock, as well as economically vulnerable countries, will see heightened snake species diversity by 2070. This increase is expected in nations like Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Uganda, and Kenya.

Study authors Pablo Ariel Martinez at the Federal University of Sergipe in Brazil and Talita F Amado at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research in Germany, Leipzig said, “As more land is converted for agriculture and livestock rearing, it destroys and fragments the natural habitats that snakes rely on.”

Some generalist snake species, especially those of medical concern, can adapt to and thrive in agricultural landscapes with food sources like rodents.”

ALSO READ: Bumble bee decline linked to climate change, threatening populations

The study authors said, “Our research shows that when venomous snakes appear in new places, it prompts us to think about how to keep ourselves and our environment safe.”

Countries like Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Uganda, Kenya, Liberia, Cameroon, Ukraine, and Lithuania will see more snake species in their agricultural regions. Habitat fragmentation due to agriculture will lead to more.

138,000 people die each year due to snake bites

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.8 to 2.7 million people suffer venomous snakebites annually. This results in up to 138,000 fatalities and at least 400,000 cases of amputations and permanent disabilities. In 2017, the WHO classified snakebite envenomation as a top neglected tropical disease.

The organization notes that people in agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, and hunting face the highest risks, especially in areas with limited healthcare. Youth are most susceptible to snakebites, and children face greater mortality risk.

These findings highlight the importance of promoting scientific research and conservation policies, especially in countries with significant snake species declines.

“We’re getting a better handle on how snakes will change their distributions with climate change, but there’s a concern they will bite more people if warm temperatures, severe wet weather events, and flooding that displaces them and others become more frequent.” “We urgently need to understand how this will affect where and how many people get bitten, so we can prepare.”

“The modelling does not consider how humans will adapt/change to climate change. Snakebite is in essence a human-animal-environment conflict. The global study addresses a significant knowledge gap,” remarked Soumyadeep Bhaumik, a medicine lecturer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney who was not involved in the research. “The new study underlines the need for countries with high [snakebite] burden to collaborate with neighbouring ones.”

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.