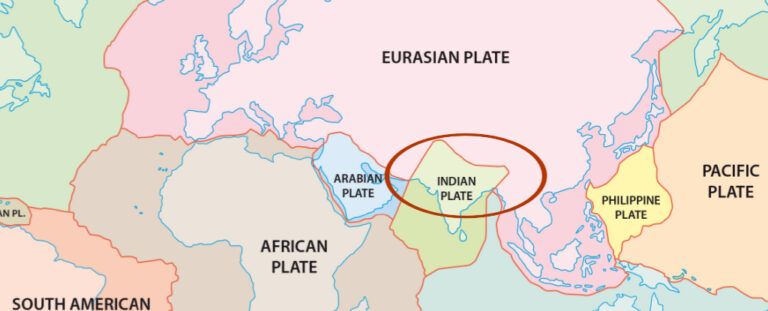

A recent study suggests that India’s geological landscape is undergoing significant transformation, with indications that the Indian Continental Plate might be undergoing a horizontal split rather than a conventional sideways separation.

The analysis of seismic data gathered from southern Tibet, coupled with a reevaluation of previous research, has unveiled a striking portrayal of the immense geological forces at play beneath the Himalayas.

Seismic data reveals Himalayan geological forces

Presenting at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco last December, researchers from institutions in the US and China unveiled findings suggesting a unique disintegration process within the Indian continental plate. As it interacts with the basement of the Eurasian tectonic plate, situated above it, the Indian plate undergoes a transformative process.

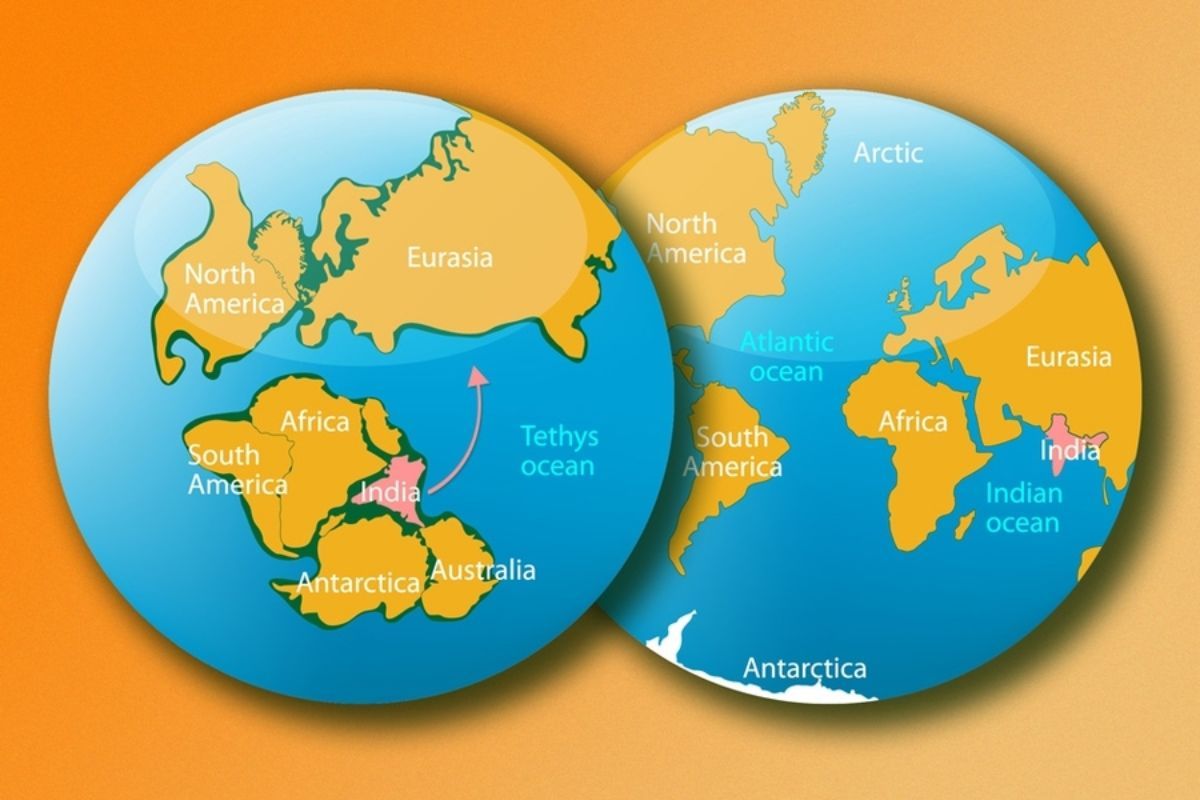

Contrary to prevailing models explaining the elevation of the Tibetan plateau and the formation of the Himalayan mountain range, this discovery offers a surprising compromise. Traditionally, these phenomena were attributed to a collision between the Indian and Eurasian crustal fragments. This collision, dating back approximately 60 million years, involved the Indian plate subducting beneath its northern neighbour, propelled by currents of molten rock within the mantle.

Scientists propose that the split is occurring in layers rather than the plate breaking into two distinct pieces. The formation of the Tibetan Plateau has sparked considerable debate within the scientific community regarding its underlying causes.

According to a January 2024 study, the Indian tectonic plate is splitting into two layers, each about 100 kilometres (60 miles) thick, as it moves towards the Eurasian plate. This process, known as “delamination”, is causing the landmass to decrease by 2 millimetres per year.

The study suggests that the plate is separating into higher and lower layers, with the elevated section contributing to Tibet’s high peaks and the lower part submerging into the Earth’s mantle.

India’s plate undergoes horizontal split

A recent study suggests that India’s geological landscape is undergoing significant transformation, with indications that the Indian Continental Plate might be undergoing a horizontal split rather than a conventional sideways separation. Scientists propose that the split is occurring in layers rather than the plate breaking into two distinct pieces.

“Levels of helium present in the Tibetan springs led us to draw our arguments,” explained Simon Klemperer of Stanford University and co-authors on the study. “Our research revealed a pattern suggesting that the mantle was close enough to the Earth’s surface for the rare helium-3 to emerge through the springs in northern Tibet,” they added.

“In southern Tibet, the prevalence of Helium-4 indicates that the plate has not yet split there,” stated Professor Douwe van Hinsbergen of Utrecht University in an interview with Science Magazine. Reflecting on the concept, he added,

“We didn’t know continents could behave this way and that is, for solid earth science, pretty fundamental,” Professor Douwe van Hinsbergen, who is not an author of the study said.

Research into the density of the mantle and crust indicates that the buoyant Indian continental plate should not sink easily, suggesting that submerged sections of the crust likely continue to grind along under the Eurasian plate rather than plunging into the depths of the mantle.

Indian plate distorts; land wrinkles, folds

Another theory proposes that the Indian plate may be undergoing distortion, causing some areas to wrinkle and fold while others dip and dive.

Diverse interpretations arise depending on the favoured evidence and data processing methods. In a study led by geophysicist Lin Liu from the Ocean University of China, researchers collected ‘up-and-down’ S-wave and shear-wave splitting data from 94 broadband seismic stations spanning southern Tibet. This data, combined with previously gathered ‘back-and-forth’ P-wave data, yielded a more nuanced understanding of the underlying dynamics.

Fabio Capitanio, a geodynamicist at Monash University, underscores the uncertainties surrounding the process, noting the limited data available. ‘It’s just a snapshot,’ he remarks. However, Capitanio acknowledges the significance of the research as a crucial step toward understanding the formation of our modern landscape. ‘It’s the type of work that we need to move [forward],’ he asserts.

Professor Douwe van Hinsbergen, who highlights the novelty of the findings said, ‘This is the first time that … it’s been caught in the act in a downgoing plate.’ Scientists have long theorized about the possibility of tectonic plates unzipping, driven by the layered composition of buoyant crust and denser upper mantle rock.

Such a split occurs along the weak interface between these layers, a phenomenon previously studied in the interiors of thick continental plates and simulated in computer models.

Earthquake risks tied to ancient collisions

A more recent analysis, based on a different set of earthquake waves, indicates a tear along the western edge of the delaminated slab. According to Anne Meltzer, a seismologist at Lehigh University, almost every landmass on Earth, including the Himalayas, was formed from similar collisions. Understanding these collisions not only illuminates our current landscape but also helps us grasp the earthquake risks along ancient continental scars.

The study’s implications are profound, extending beyond mountain formation to earthquake prediction. By gaining a clearer 3D insight into tectonic plate interactions, scientists can enhance understanding of Earth’s surface changes and potentially improve seismic event forecasts.

Celal Sengor, a professor of geological engineering at Istanbul Technical University, who was not involved in this research, remarks, “India was going far too fast after it parted company with Africa-Madagascar and Australia. … Its speed northward, concerning the rest of Eurasia, was faster than any plate motion we know today, or have inferred in the past across a single plate boundary. This paper not only has changed some of our ideas on the paleotectonics and paleogeography of the neo-Tethys but has given us a new model about what double subductions can do.”

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.