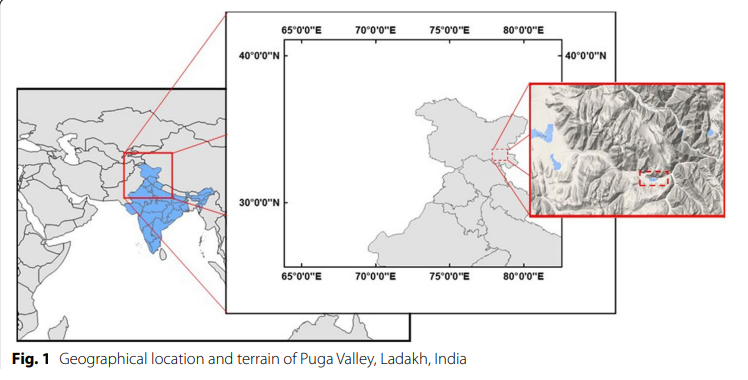

In the remote, high-altitude desert of Ladakh, Indian and Icelandic engineers have commenced work on India’s first geothermal plant at Puga Valley. As drilling progresses, large quantities of steam emerge from the ground, confirming the region’s potential. The Puga Valley, 190 km from Leh at 4,400 meters, is set to become home to India’s first geothermal power plant.

Geothermal is deemed renewable because the Earth’s internal heat is virtually limitless and will persist for billions of years. Unlike solar and wind energy, geothermal energy is available 24/7, year-round. It emits approximately 80% fewer greenhouse gases than coal and oil.

What are geothermal power plants?

As mentioned, geothermal power plants use the Earth’s internal heat to generate electricity. There are three main types of geothermal power plants: dry steam, flash cycle, and binary cycle. Dry steam plants use natural steam. Flash cycle plants use high-temperature water that turns to steam. Binary cycle plants use lower-temperature water to heat another fluid that vaporizes to drive the turbines.

In Puga Valley, engineers are tapping into this potential by drilling deep into the ground to access hot water and steam to turn turbines and generate electricity. This zone shows evidence of geothermal activity in the form of hot springs, mud pools, sulphur and borax deposits.

Ladakh, known for its glaciers, is already grappling with a severe water crisis. The whole region relies primarily on snowmelt and glacier runoff for its water supply. The introduction of geothermal power plants in the region could further impact both water quality and consumption. Geothermal power plants often use water for cooling and re-injection processes.

Why was Puga Valley chosen?

The choice of Puga Valley for this project is no coincidence. Its geological features, including over 350 natural hot springs and its location at the junction of the Indian and Tibetan tectonic plates along the Indus Suture Zone, make it an ideal site for geothermal energy. Dr. Riyaz, a geology professor at the University of Leh, explains,

“The collision of two tectonic plates under Ladakh creates a geothermal hotspot, making it an excellent source of renewable, zero-carbon energy.”

A 2017 study estimated that Puga Valley could generate 5,000 MWh of geothermal energy for electricity, heating, and greenhouse cultivation, with some experts suggesting a potential 250-300 MW capacity. A 20 MW geothermal plant at Puga could save three million litres of diesel burnt annually in the region at a cost of approximately USD 2 million.

The potential of Puga Valley has been known for decades. In the 1980s, the Geological Survey of India conducted extensive explorations. Ahsan Absar, a former GSI geologist now consulting with ONGC, recalls,

“We made 34 boreholes, ranging from 28.5 m to 384.7 m, and found a maximum temperature of 140 degrees Celsius at the lowest depth.”

In 2021, the Indian government proposed the Puga Valley Geothermal Power Project to address energy shortages in remote areas. In February 2021, the ONGC Energy Centre signed a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council and the Union Territory Administration to establish a 1 MW experimental geothermal power plant in Puga Valley. The drilling began in August 2022, revealing higher-than-expected temperatures at shallow depths, indicating strong geothermal activity.

Sunil Kumar, Project Associate at ONGC Energy Centre, reports encouraging progress, “We’ve started the drilling work. Our initial target is to generate one megawatt of power. Initial results are promising, with temperatures of 100 degrees Celsius found at just 35 meters depth.”

A pilot project generating 1 MW of power is expected to be completed by the year’s end, providing free electricity to 10 neighbouring villages, marking India’s first geothermal energy production project. In addition, there are plans to dig deeper and larger wells to tap into the site’s estimated potential of over 100 MW.

The project aims to do more than just generate power. Uday Shankar, the project manager of ONGC Energy Center, envisions various applications,

“Geothermal power can heat Army bunkers and homes, support greenhouse agriculture, assist aqua farming, and develop hot swimming pools for tourism.”

Environmental Concerns Over Geothermal Project

The project has challenges and controversies. Puga Valley is part of the Changthang Wildlife Sanctuary, home to endangered species such as the snow leopard, Himalayan wolf, and six species of wild ungulates, and crucial wetlands for migratory birds. Tsewang Namgyal, director of the Snow Leopard Conservancy, voices concern,

“These are the most productive ecosystems in Ladakh, for wildlife and nomads. We need to know how this project might impact the ecosystem.”

He cautiously supports the project, and said, “We’re not against the project, but we want proper environmental norms.”

Despite the promise of clean energy, the project has raised environmental concerns. On August 16, 2023, a ‘blow out’ occurred during drilling, spewing breccia, bentonite, steam, and hot water into the Puga stream. This alarmed local environmentalists, and they reported the issue to the Leh district collector with evidence, concerned about the environmental impact on Sumdo village and local wildlife that rely on the stream for water. This prompted a district administration investigation.

In the United States, these facilities typically employ wet-recirculating technology with cooling towers, consuming between 1,700 and 4,000 gallons (which is 6435.2 litres to 15141.65 litres) of water per megawatt-hour, depending on the cooling technology used. While geothermal plants can utilize either geothermal fluid or freshwater for cooling, opting for geothermal fluids significantly reduces the overall water impact compared to using fresh water.

Meanwhile, according to a study by the Ladakh Ecological Development Group (LEDEG), an environmental NGO based in Karzoo (Leh), an average Ladakhi uses 21 litres of water per day during summer and 10-12 litres during winter, while a tourist needs as much as 75 litres. Hence, the project can create a water crisis in an already water-scarce region.

Way forward

Jigmet Takpa, Director of the Ladakh Renewable Energy Development Agency (LREDA), said,

“We need to reach a depth of at least 2 km to understand the temperature variations and determine if the heat is from the earth’s core, magma, or lava,” Takpa explained.

“Geothermal energy is not affected by weather. Its efficiency is consistently high, and it does not require storage. Over time, the cost will decrease, similar to coal, but without the environmental impact of burning coal. Instead, we harness steam for free,” Takpa explained. However, initial costs are substantial due to the need for imported drilling technology. The capital cost of generating energy from geothermal sources in India is estimated to be US$1.6–2.0 million per megawatt electric (MWe), but the operating cost is minimal.

According to a Stanford University study, large-scale geothermal power plant development can have significant environmental impacts. Repairing damaged underground loops is difficult and costly, making maintenance a significant issue. Additionally, since geothermal energy is harnessed near tectonic plate boundaries, drilling can potentially trigger earthquakes.

Geothermal power plants require significant investment and heat pumps need a large amount of electricity. There are constraints like a shortage of exploitable areas, unacceptable gas emissions, and remote locations far from load centres. The industry grapples with a lack of advanced technologies, funding problems, and lengthy development periods of 5 to 10 years. Drilling, the most complex and expensive process, needs innovative geo-technological solutions to reduce costs and risks.

There is potential to harness an unparalleled amount of renewable energy. At the same time, considering the vulnerability of the region, people have their concerns. The government needs to conduct a thorough environmental assessment, among other economic concerns, with relevant stakeholders to instil trust among people for the project. There is a lack of trust between Ladakhis, and the Government of India, and this project can be a way to resolve the difference by ensuring transparency in the process of project implementation.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

What is Green Hydrogen? Could it change energy in South Asia?

Blue hydrogen is worst for climate: study

How Increasing space traffic threatens ozone layer?

Hydro Fuel Market: India’s current scenario and the future ahead

Natural Gas is a Misleading term, It is not Natural and clean at all

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.