In the heart of Dobra village, nestled within the Nonikhedi Panchayat of Sehore district, a poignant scene unfolds beneath a board that boldly declares “Beti hai toh kal hai” (If there’s a daughter, there’s a tomorrow). Ironically, the promise of future hope stands in stark contrast to the daily struggle of the village’s daughters. Poonam, a BSc student at Sehore’s Swami Vivekanand College, and other young girls navigate the harsh realities of water scarcity, balancing their bicycles under the weight of four heavy water cans.

“We have a critical water problem,” Poonam shares, her voice steady but tinged with frustration. “This hand pump provides water only for a few days. After that, we’re forced to travel several kilometers just to fetch water for our families.” Her daily routine is a testament to resilience—rise before dawn to collect water, prepare for her 13-kilometer journey to college, all while knowing the task will become even more challenging during the cold winter months.

A local woman nearby echoes Poonam’s sentiments, revealing a deeper social dimension to this water crisis. “This water shortage has plagued our village for years,” she explains. “And the burden falls entirely on women. The men of the household offer no assistance; water collection is seen as solely our responsibility.” Her words paint a stark picture of gender dynamics that compound the already difficult challenge of water scarcity.

Falling groundwater level

The month of November is the time for sowing of Rabi crops in Madhya Pradesh. In such a situation, farmers need water for irrigation. In Dobra village, farmers depend on groundwater for irrigation.

According to the Central Ground Water Board 2021-22 report, the groundwater level has declined in most areas of Sehore district; in some places this decline is more than 2 meters. The DTW-Depth to Water Level is 10-20 meters below in many areas, which highlights the relatively deep groundwater level.

The Madhya Pradesh Water Resources Department considers excessive exploitation of groundwater for agricultural activities in Sehore district as the main reason for this decline.

Amidst his fields, Devendra Tyagi guides his tractor with a palpable sense of frustration, his voice carrying the weight of agricultural challenges. “We’re battling twin crises of water and electricity,” he declares, his eyes scanning the parched landscape.

“Our nights are consumed by irrigation, staying vigilant to water our crops. If every field starts using tubewells, we’ll drain the underground water reserves completely. Then we’ll be reduced to begging for drinking water from door to door.”

With a sharp gesture towards a dilapidated transformer hanging precariously on an electricity pole, Devendra’s anger becomes more pronounced. “We live in constant uncertainty,” he explains. “This transformer could fail at any moment. When it does, we’ll be forced to contact the electricity department; they never respond promptly.”

The villages of Dobra and Barkheda Sukal, situated within the Nonikhedi Panchayat, epitomize rural water distress. Dobra village bears the brunt of this crisis, with groundwater becoming increasingly elusive – barely traceable even at depths of 250 feet. Jyoti Dangi serves as the Sarpanch, though her husband Pradeep Dangi manages the administrative responsibilities.

When questioned about the water crisis, Pradeep offers a pragmatic yet somewhat resigned perspective. “Resolution is impossible without community action,” he asserts. “Only through collective protest can we hope to create meaningful change.” He acknowledges the ongoing Nal Jal Yojana project but highlights a critical bottleneck—identifying a suitable location for the water supply tank.

“Har Ghar Jal officials insist on a slightly elevated site to ensure efficient water distribution,” Pradeep explains. “However, such a location is unavailable in the village. Government land is insufficient, and local farmers are reluctant to donate their private land for the project.” He has proposed alternative land options, but a final decision remains pending.

Praveen Saxena, the Har Ghar Jal Officer for Sehore district, offers a bureaucratic perspective. “Such challenges are not uncommon,” he states matter-of-factly. “Typically, the local Patwari identifies and resolves site-related issues.” He remains optimistic about the Nal Jal Yojana, emphasizing that all water tanks will eventually connect to the Narmada pipeline, promising water access to groundwater-deficient villages by September 2025.

Saxena acknowledges the project’s complexities—land acquisition challenges and forest clearance obstacles continue to impede progress. Yet he maintains that these hurdles are progressively being addressed.

What do the figures say?

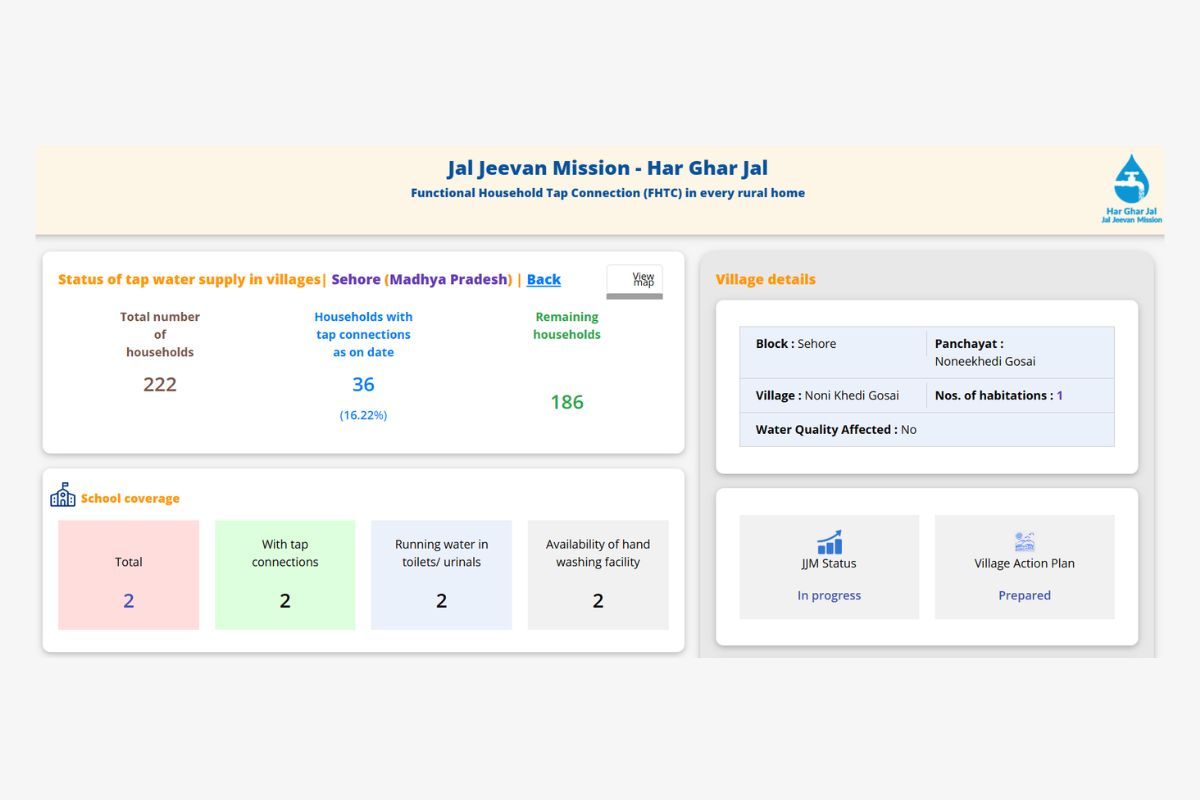

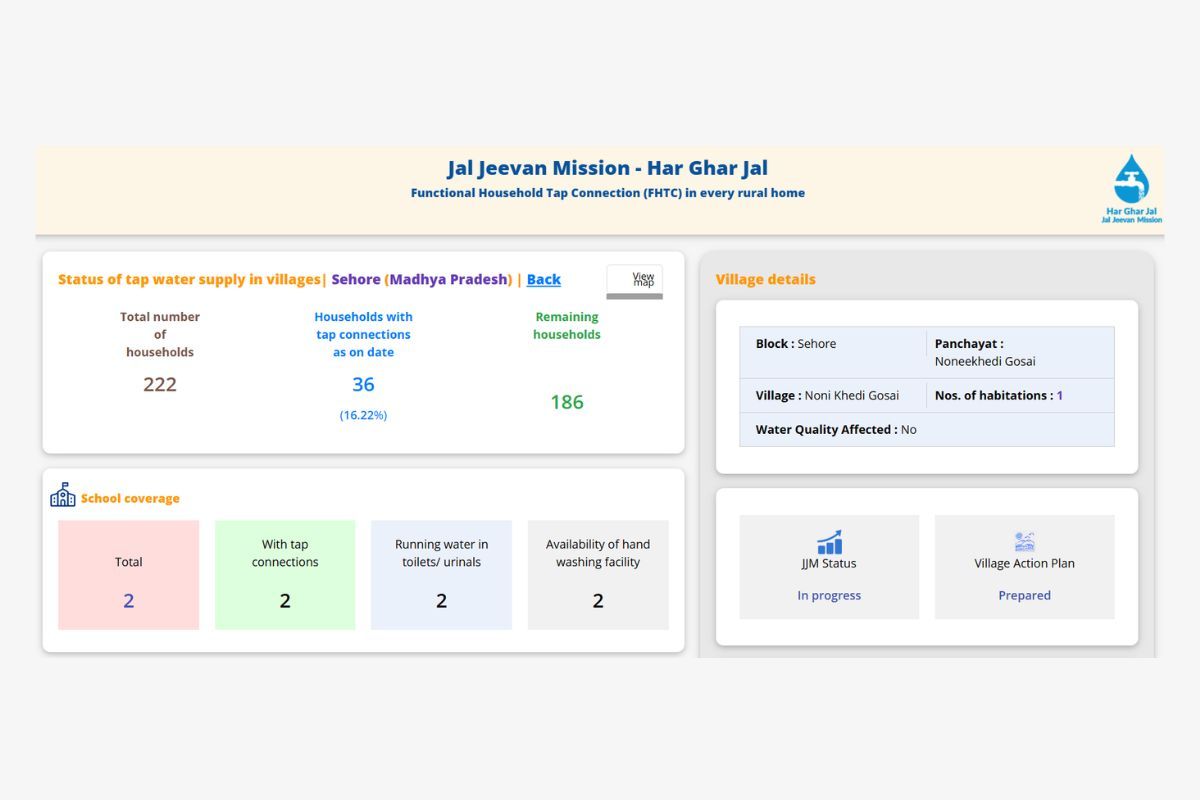

According to the Jal Shakti portal, out of 222 houses in Nonikhedi village, only 16 percent, i.e., 36 houses, have water connections.

On this figure, Pradeep Dangi says that “under the Har Ghar Jal Yojana, there is not a single connection in our panchayat because the work has just started. The 36 houses that are being talked about are the figures of people’s personal connections.” Pradeep gives an example that he himself has brought water to the house by laying a pipeline from his farm.

That is, in these figures, those houses are also being counted that have arranged water on their own.

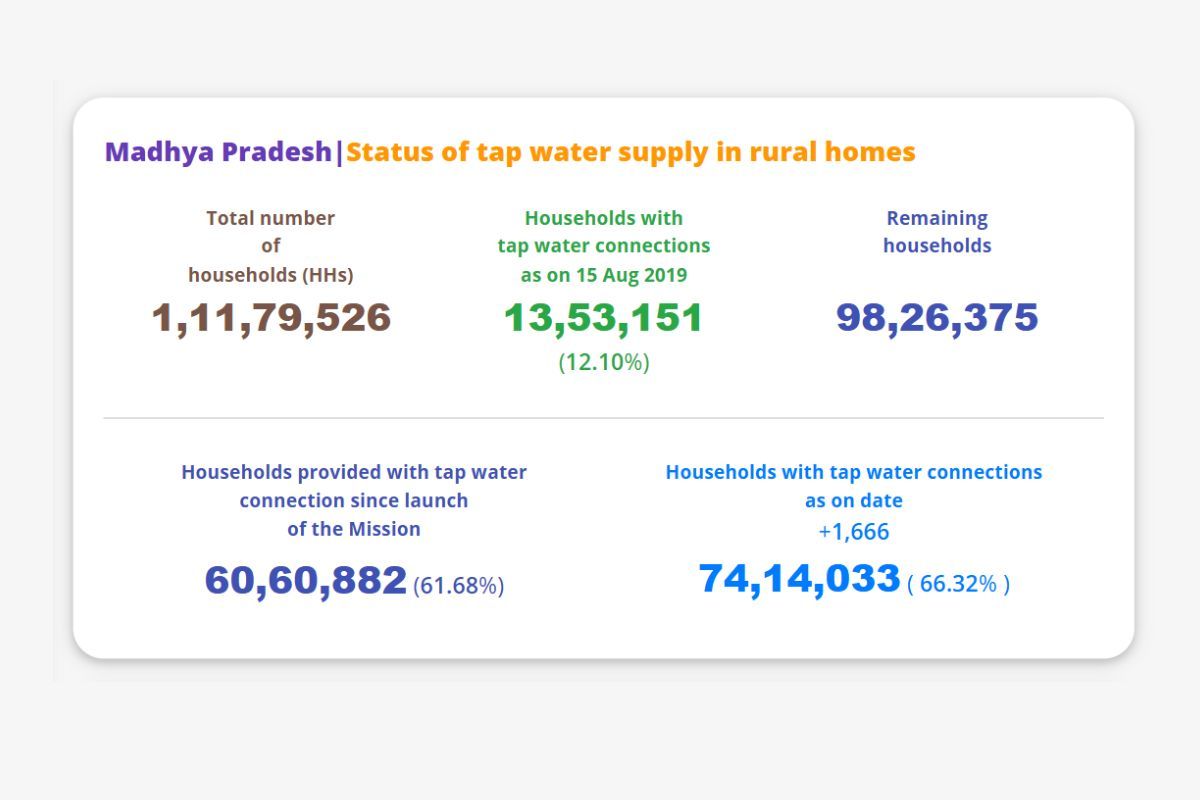

According to the Har Ghar Jal Dashboard of Jal Jeevan Mission, out of a total of 1,1179,526 rural houses in Madhya Pradesh, by November 2024, 74,14,033 houses have been given water connections. That is, the connection has reached 66.32 percent of the houses.

Out of total 51,011 villages in Madhya Pradesh, 16,835 villages have a tap water scheme reaching 100% of the houses. Out of these, 9,726 villages have certified that water is being supplied to every house.

This data shows that a tap connection reaching them does not mean that water supply has started. We get confirmation of this by visiting Chanderi village in the Phanda block of Bhopal, where according to the Jal Shakti portal, 100% of the houses have tap connections. But ground investigation shows that the construction of the tank for water supply in these taps is still incomplete.

Praveen Saxena says that “the infrastructure of water supply being built for ‘Har Ghar Jal’ will be completed only after the Narmada line starts. Water will reach these tanks from this Narmada line. But till then, if any panchayat manages to fill these tanks through borewell or any other means, then it can do so.”

Poonam fills her water cans one by one from the hand pump and carefully hangs them on her cycle. She says, “Right now we are getting water from this government hand pump in the village; after a few months when it dries up, we will have to go several kilometres away and fetch water from those houses who will take pity on us and let us take water from their borewells. Then there will be a long queue, and more time will be wasted.”

Poonam rides her bicycle forward and turns towards her house. Nearby, on the roadside, there is a bus stop built by former MP Sadhvi Pragya, on which her smiling picture is placed. But perhaps a smile on Poonam’s face will appear only when her water problem gets solved.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

From pollution to preservation: Reviving Indore’s Annapurna Lake

Sirpur Wetland: Illegal buildings razed, fight for STP removal continues

Costliest water from Narmada is putting financial burden on Indore

5 projects of Modi government that will cause irreversible impact on environment

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.