Lightning-related deaths have seen a significant increase in India, particularly since 2001, with Central and North East India being the most affected regions. The phenomenon, driven by a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors, poses a growing threat to communities, especially in rural areas. Professor Mishra delves into the key drivers behind regional vulnerability to lightning, the role of climate change, and the necessary policy changes to mitigate this hazard.

A recent story titled: “Lightning-related fatalities in India (1967-2020): A detailed overview of pattern and trends” carried out by Manoranjan Mishra, Tamoghna Acharya, Rajkumar Guria, Nihar Ranjan Rout, and others. The study collected lightning fatality data from 1967 to 2020 (53 years) across Indian states from the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB), which provides the longest available time series of gender-disaggregated lightning fatality data.

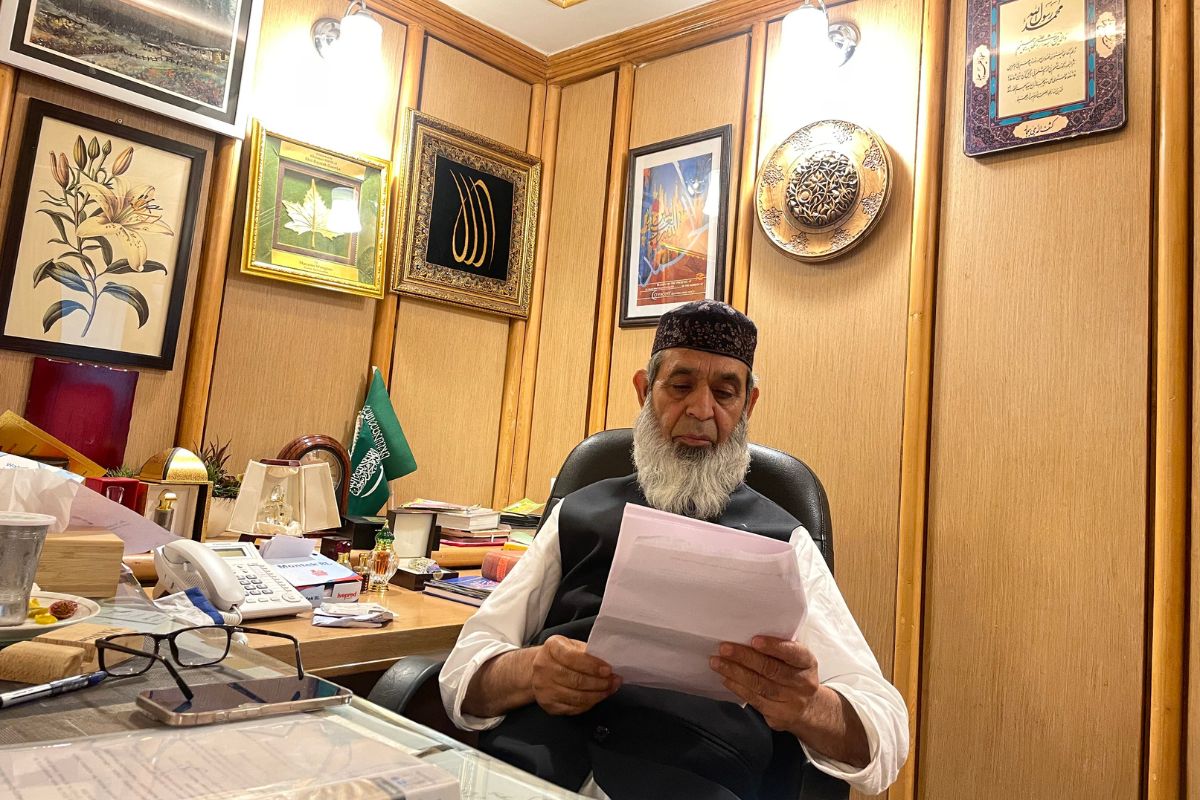

In an interview with Ground Report, Manoranjan Mishra, a lightning expert and Professor at Fakir Mohan University in Balasore, Odisha, discussed the significant increase in lightning-related deaths in Central India, attributed to extensive mining activities, deforestation, and climate change. He emphasized the need for targeted public awareness campaigns and mitigation strategies to reduce lightning fatalities, particularly in rural areas where the majority of deaths occur.

Mishra also highlighted the importance of developing low-cost lightning protection systems and incorporating lightning safety measures into building codes to achieve zero lightning-related deaths in India.

Interview

(GR): Your research highlights an increase in lightning-related deaths in India, particularly in Central and North East regions post-2001. What do you believe are the key drivers behind this regional vulnerability? Are there specific socio-economic and environmental factors contributing to this?

Manoranjan Mishra (MM): The central part of India is more vulnerable to lightning hazards compared to Northeast or South India. One reason is the extensive mining activities in Central India, which create aerosols that contribute to lightning activity. Additionally, the region experiences significant heating as the temperature starts increasing with the availability of moisture during the pre-monsoon period, leading to more lightning activity. Socio-economic factors also play a crucial role, such as the number of people exposed to lightning, especially those working in agriculture, as labourers, or grazers who spend long hours outside. In contrast, in the Himalayan region, most lightning activity occurs at night when people are indoors, leading to fewer casualties. The convection process starts around 12 o’clock, and the majority of deaths occur between 2 o’clock and 7 o’clock in the central part of India.

GR: There seems to be a higher number of deaths in states like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra compared to other parts of the country. What might be the possible reasons for this?

MM: The population density is one factor—larger states like Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra naturally have more casualties. Odisha also has a higher number of recorded deaths, partly due to better recording practices, especially post-2000, as Odisha was one of the first states to offer compensation for lightning deaths. Additionally, climate change and anthropogenic changes like deforestation and aerosols in the atmosphere contribute to the increasing frequency and intensity of lightning activities in these regions. The death toll has increased from around 1,800 deaths per year before 2000 to more than 2,800 to 3,000 deaths per year currently. This increase may also be due to better recording and climate change effects.

GR: You mentioned climate change’s impact on lightning activity, with a 40% increase in lightning for every one-degree rise in global temperature. Could you elaborate on how climate change is influencing lightning patterns in India and what future trends you foresee?

MM: There is a non-linear relationship between climate change and lightning activity. A small increase in maximum temperature can add significant moisture to the atmosphere, making it thermodynamically unstable and leading to more lightning events. Lightning activity is a localized phenomenon, but the causes can be regional. For example, places near the Bay of Bengal coastline or close to mountains experience more lightning activity due to orographic lifting. As global temperatures rise, more moisture will be loaded into the atmosphere, resulting in more extreme events like lightning. The intensification of lightning depends on several factors, such as elevation, convective available potential energy, and ground conditions. While it is difficult to predict trends linearly, the pattern suggests that with an increase in temperature, lightning activity will also increase.

GR: With such an increase in lightning activity, what is the current trend of cloud-to-ground lightning in India, and how many such lightning strikes occur each year?

MM: We are still in the process of gathering five-year data from sources like IITM Pune and NRSC Hyderabad, which will allow us to analyze and determine the exact trend. Reports indicate an increasing trend in cloud-to-ground lightning activity in different parts of India, but it varies depending on several factors. While the death pattern shows a high correlation with cloud-to-ground activity, we still need more precise data to confirm these trends.

GR: Given the rising trend in lightning fatalities, what role do you see for early warning systems and mobile apps like Damini in reducing these deaths? How effective have these tools been in practice?

MM: Early warning systems and apps like Damini can be useful, but their effectiveness is limited. The accuracy of these systems can be improved, but there are still limitations. For example, the Damini app can provide live tracking of lightning activity in your area, but it requires people to actively use the app and respond quickly. However, many people in rural areas do not have access to smartphones, making it difficult for them to benefit from these tools. Therefore, we need to focus on educating people about how to recognize the signs of lightning activity and take appropriate action, such as avoiding being the highest point in an area or seeking shelter in safe structures.

GR: Many people in rural India do not own smartphones and are unaware of apps like Damini. How can we ensure that they receive accurate information about lightning risks?

MM: This is a significant challenge. For those without smartphones, we need to rely on public awareness campaigns and physical observation. People need to be educated on recognizing the signs of lightning, such as dark clouds or sudden changes in weather, and taking appropriate action. Community radios and public announcements can also be used to disseminate warnings and safety advice. Additionally, creating safe shelters in agricultural fields and redesigning houses in rural areas to be lightning-resistant can help reduce fatalities. We should also consider using public places, like village boards or Gram Panchayats, to display warnings and advisories.

GR: Despite the availability of these mitigation strategies and early warning systems, lightning fatalities have consistently increased in India. What are the key challenges in implementing these solutions effectively, and why haven’t we been able to overcome them?

MM: The key challenges lie in the accuracy and scale of early warning systems, as well as in the effectiveness of public awareness campaigns. Forecasting models often lack the precision needed to predict lightning at the point level, leading to warnings that are not taken seriously by the public. Additionally, public awareness campaigns have been too generalized and not targeted enough to reach the most vulnerable populations. Many officials and experts involved in disaster management do not fully understand the complexities of lightning hazards, leading to ineffective planning and implementation. To overcome these challenges, we need a more targeted approach that includes vulnerability mapping, increased public education, and physical outreach to communities at risk.

GR: Given the ongoing challenges, what policy changes do you think are necessary at the national level to achieve zero lightning-related deaths, and how can your research findings inform future policy decisions?

MM: At the national level, we need to declare lightning a national disaster, which would bring more attention and resources to this issue. We also need to develop comprehensive vulnerability maps at the district level that combine lightning flash density data with socio-economic factors to identify high-risk areas. Policies should prioritize mitigation and public awareness over forecasting, as the latter has significant limitations in accuracy and effectiveness. Building codes should be updated to include lightning protection measures, especially in rural areas, and low-cost lightning protection systems should be developed and implemented. Finally, the government should focus on reaching the “last mile”—the people who are most vulnerable to lightning strikes—through targeted public awareness campaigns and community education efforts. These steps, informed by research, are crucial to achieving zero lightning-related deaths in India.

GR: You mentioned the importance of incorporating lightning safety measures into building codes and public infrastructure. What specific changes do you recommend, and how can these be effectively enforced in both urban and rural areas?

MM: We need to incorporate semi-Faraday cage designs and Franklin rods into building codes, particularly in rural and tribal areas where houses are more vulnerable. The concept of semi-Faraday cages involves using metal beams and rods in the construction of buildings to absorb and safely discharge lightning currents. In rural areas, we should focus on low-cost solutions that can be easily implemented without significantly increasing construction costs. The government should bring together experts in high-voltage engineering to design these low-cost lightning protection systems and ensure that they are included in the construction of new buildings, particularly in regions that are most at risk.

GR: You’ve emphasized the need for public awareness in reducing lightning fatalities. Despite this, lightning deaths have continued to rise. What are the main reasons for this, and how can we overcome the barriers to effective implementation of these solutions?

MM: The main reason for the continued increase in lightning fatalities is the lack of targeted public awareness campaigns. Most of the current efforts are superficial and not reaching the people who are most at risk, particularly those in rural areas who are out of the digital loop. Many awareness campaigns focus on general information that doesn’t address the specific behaviors and situations that lead to fatalities. To overcome these barriers, we need to focus on the “last mile”—the individuals who are most exposed to lightning hazards. This includes conducting physical outreach to educate these populations, as well as developing simple, actionable safety guidelines that can be implemented at the local level. The government should invest in training local officials and community leaders to deliver these messages and ensure that they reach the people who need them most.

GR: Considering the goal of achieving zero lightning-related deaths, what specific policy recommendations would you suggest to both state and national governments?

MM: First, lightning should be declared a national disaster, which would allow for more focused planning and resource allocation. We need to create detailed vulnerability maps at the district level, combining lightning flash density with socio-economic data to identify high-risk areas. Policies should shift from focusing primarily on forecasting to include targeted public awareness and mitigation strategies. We also need to incorporate lightning safety measures into building codes, especially for rural areas, and develop low-cost lightning protection systems for homes and public infrastructure. The government should invest more in public awareness campaigns and ensure that these reach the most vulnerable populations. Training local officials and communities on lightning safety and ensuring that information reaches those who are most at risk is crucial for achieving zero casualties.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

The costliest water from Narmada is putting a financial burden on Indore

Indore’s Ramsar site Sirpur has an STP constructed almost on the lake

Indore Reviving Historic Lakes to Combat Water Crisis, Hurdles Remain

Indore’s residential society saves Rs 5 lakh a month, through rainwater harvesting

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.