Bineki village, located in Seoni district, lies about 360 km from Bhopal, the capital of Madhya Pradesh. Travelling through the area by train, you’re greeted by lush green fields on either side.

However, stepping into Bineki presents a stark contrast. Towering over the village is the chimney of the Jhabua power plant, surrounded by rows of empty houses—most of the village lies deserted.

The village, however, can ‘boast’ of the Jhabua Power Plant—a 600 MW coal-based thermal power plant. But for the locals, this plant has reportedly been more of a bane than a boon. Farmers allege that ash generated by the plant has damaged their fields and polluted the local waterway, a natural drainage canal known as Gode Nala. This canal is a vital lifeline for farmers, birds, and animals who depend on it for water.

The plant authority claims that they are utilising the ash according to the norms. One of the employees even told Ground Report that the plant has helped the local farmers to reclaim their barren fields.

Farmers are turning to labourers; reality differs from the claim

Sixty-five-year-old Maniram, a farmer from the village, used to cultivate paddy during the Kharif season and wheat during Rabi. However, for the past three years, his 2.5-acre farm has remained barren. The reason? Fly ash from the nearby plant.

Maniram’s farm is situated on the banks of the Gode Nala. “When the ash started falling, the grains stopped growing. Now the field is just lying there,” he says. Repeated crop failures due to pollution forced him to abandon farming on the land.

Maniram now works as a labourer to support his family’s livelihood, earning between ₹200 and ₹300 a day. When asked how his family manages to get by, he says,

“Everyone goes out to work, each can bring in some money.”

He has two grandsons, both working as labourers in Jabalpur, 126 km from the village. His daughter-in-law, too, shares a similar fate. Many farmers in the village tell us a similar story.

Located on the Gorakhpur-Barela border, the plant generates electricity from coal. After the coal is burnt for energy, the resulting ash is collected and categorised into fly ash and bottom ash.

Fly ash is a fine powder, while bottom ash consists of heavier particles that settle at the bottom of the boiler.

Anoop Srivastava, from the environment department of the Jhabua power plant, explains that the plant utilises fly ash in four ways, as per regulations: highway construction, cement production, brick manufacturing, and the reclamation of wastelands.

It is believed that many elements like sodium, potassium and zinc present in ash can increase the productivity of crops. So it is being used in barren land. Srivastava claims that ash has been “reclaimed” by dumping it in fields in Para, Umrapani and Rajgadhi villages of Seoni district.

However, when we sought information from the plant about the farmers whose fields had been reclaimed, they refrained from providing any details. According to some news reports, the plant had contracted to fill ash in the fields of certain farmers in Umrapani in 2022. The project was scheduled to be completed by June 2023.

In 2024, however, ash was dumped without authorisation on the fields of 20–22 farmers in the villages of Umrapani, Bhattekhari, and Rajgadhi. This prompted local farmers to stage a protest against the plant.

Shripad Dharmadhikari, founder-coordinator of the Manthan Adhyayan Kendra, which analyses environmental policies, and author of several studies, including Coal Ash in India, explains that while adding ash to fields may seem beneficial in the short term, it introduces heavy metals into the soil.

“When ash mixes with water and enters the fields, it leaches more quickly, which reduces the fertility of the soil. Additionally, dry ash particles block the stomata of plants, causing them to dry out,”

Dharmadhikari’s words are a stark reminder of Maniram, who had to abandon farming when his fields stopped producing grain and now survives as a labourer.

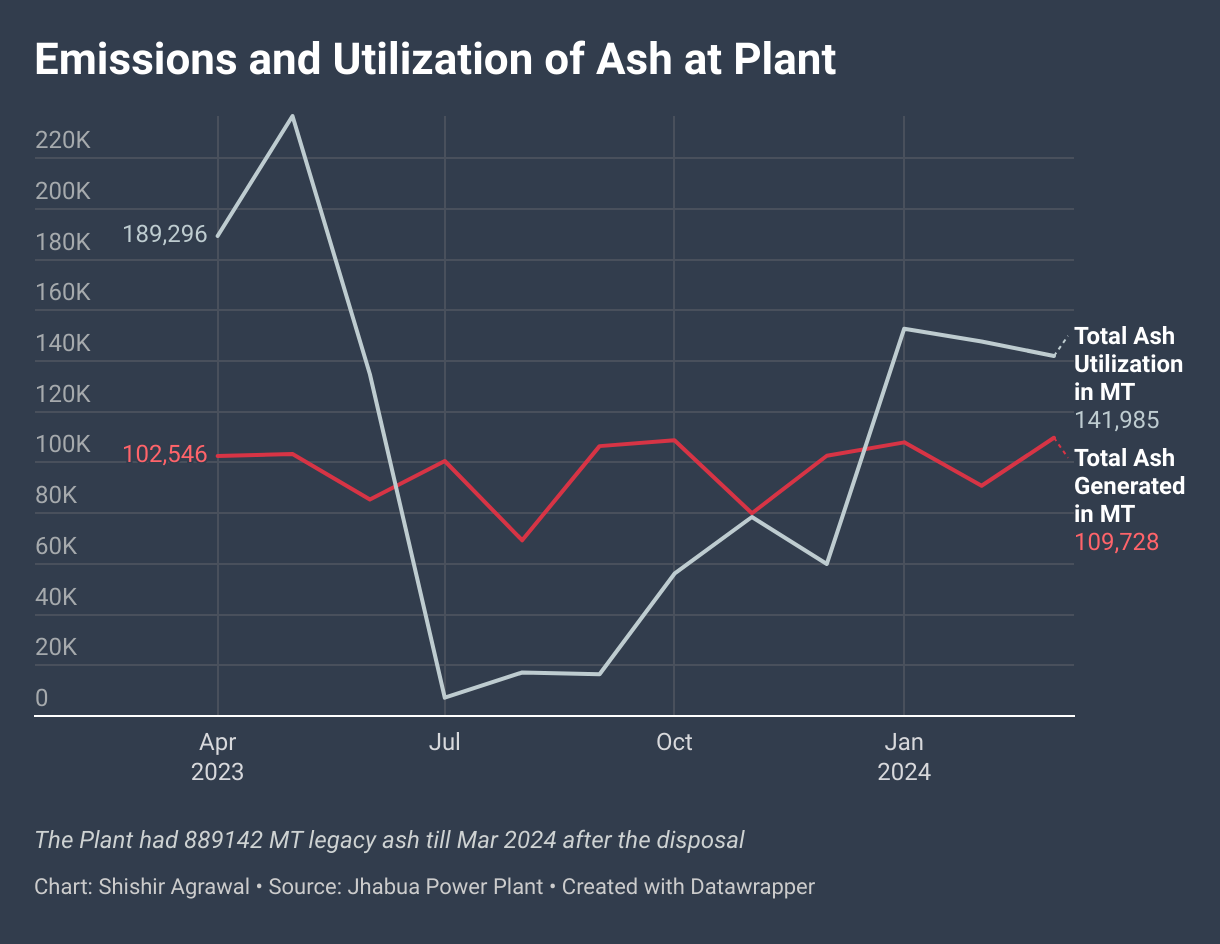

Ash Calculation: Emission versus Utilisation

According to the information available on the plant’s website, 29,18,265 million tonnes of coal have been used for power generation from April 2023 to March 2024.

During this period, 11,67,308 tonnes of fly ash and bottom ash were produced. Of this, 57,8,388 million tonnes of ash has been used. At the same time, 83,5,086 million metric tonnes of ash have been dumped in the low-lying area.

Thus, as per the data of 2023-24, the plant has used a total of 106.10% ash, including legacy ash (ash present in the plant for a long time). But these figures do not give a clear picture.

In fact, by the end of March 2024, the plant had 17,24,228 million tonnes of legacy ash. Of this, only 8,35,086 million metric tonnes of legacy fly ash have been used so far. That is, only 48.43 per cent of legacy fly ash could be used.

According to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s notification dated December 31, 2021, coal-based thermal power plants are required to use 100 per cent of the emitted ash.

Story of coal and ash in India

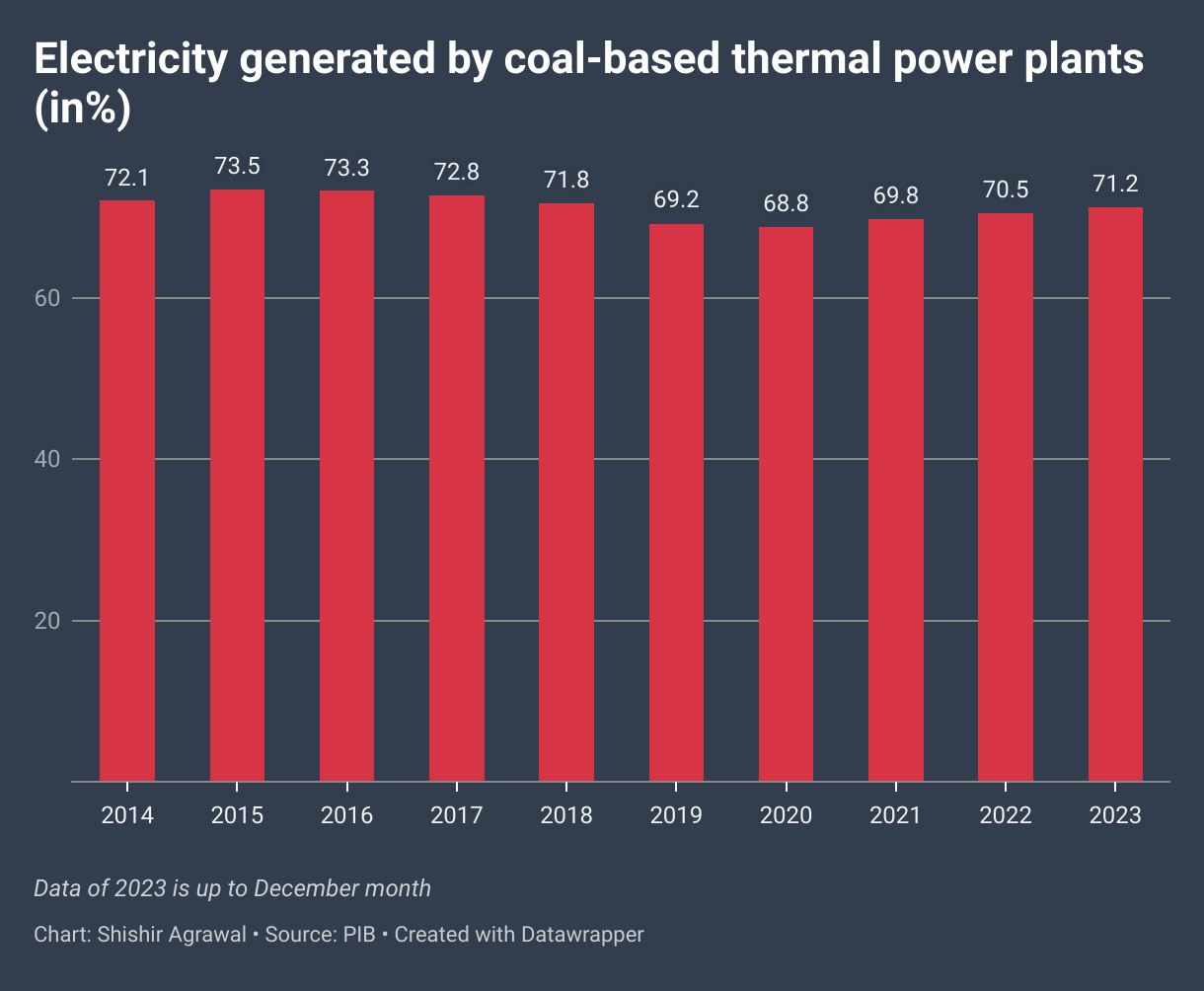

About 71.22 per cent of India’s power is generated from coal-based thermal power plants. The total generation capacity of 180 thermal power plants in the country is 212 gigawatts (GW), which is to be increased to 260 GW by 2030.

It is important to note that Indian coal used by these power plants has 30-45% ash content. Whereas coal coming from abroad has only 10-15%. This simply means that the use of Indian coal is also one of the reasons for the fly ash problem in the country.

Coal-based thermal power plants are among the 17 most polluting industries in the country. These plants had produced around 226 million tonnes of fly ash in the country in 2020.

The Jhabua power plant mainly uses coal produced in India. Such plants are called domestic coal-based plants. However, these plants also use some amount of coal imported from abroad for blending.

From 2018 to December 2023, the domestic coal-based plants across the country imported a total of 115.9 million metric tonnes of coal at an average of 19.31 million metric tonnes. In 2022–23, this import was the highest at 35.1 million tonnes.

But in the year 2023, 777 million tons of coal were used by 180 thermal power plants in the country. Of this, only 55 million tonnes of coal were imported. This means that our power plants are heavily dependent on coal produced in India.

No compensation to the farmers

Mukund Kumar Singh, an official at the Jhabua power plant, asserts that they are following environmental norms ‘word by word and 100 per cent.’

However, Mohanlal Yadav (55) from Bineki village offers a different perspective. Yadav, who once cultivated 15 acres of land, has seen his 5-acre farm lie barren since 2016. He claims that a continuous flow of ash-laden water from the plant has made it impossible for him to grow crops.

Speaking about the loss, Yadav says:

“We used to earn 2.5 to 3 lakh in both seasons by cultivating 5 acres, but since 2016, we have been losing so much every year.”

His wife Sakhi Yadav says that since 2016, they have married two children, which has increased the financial burden on them. She says that if the plant owners do not compensate them for their losses, then the plant owners should buy their land. But as per Mrs. Yadav, the plant is denying both.

Gaurishankar Nema, a journalist with a Hindi daily who has been covering the case locally, claims that trucks carrying ash from the plant to Jabalpur are passing through rural areas without authorisation. He explains,

“According to government regulations, the load capacity of roads built under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana is 8 tonnes, while each truck carrying ash weighs 60-70 tonnes.”

Ravi Agarwal, a Ghansour-based journalist too, complains about the ash. He says that the ash falling from these trucks impacts several villages between the plant and Jabalpur. He told us that the MPPCB had issued notice against the plant for mishandling the ash while transporting it to Jabalpur, but that was ineffective.

Social activist Kanti Lal Nema stated that the villagers had demanded compensation of ₹25,000 per season from the plant administration.

“The plant administration forwards the compensation request to the tehsildar, but they say, ‘We can’t offer more than ₹5,000,'” he said.

Nema criticises the ₹5,000 compensation as a “dirty joke” played on the farmers.

Why is fly ash a serious issue?

Dharmadhikari believes that the non-management of fly ash is a serious issue. But it usually goes unnoticed because most of the people affected belong to marginalised communities.

“There is a law, but whether it’s a private company or a government plant, no one seems to take responsibility. When this is discussed, it is often argued that power generation is crucial for the country and cannot be halted.”

He explains that dry fly ash travels longer distances in the air. It contains heavy metals like arsenic, lead and mercury that enter the body through the respiratory tract. According to the Coal Ash in India report, it can cause skin infections, lung and prostate cancer, and permanent brain damage.

Coal production in India has been growing at a rapid pace. Its production in 2019-20 was 730.87 million tonnes. This has increased to 997.82 million metric tonnes in 2023–24. Due to this increase, the government has reduced the import of foreign coal by 3.1 percent. India has already set a target to increase the capacity of coal-based thermal power plants to 260 GW by 2030.

These figures indicate that the problem of ash emissions from these plants will worsen in the coming days. Therefore, urgent measures must be taken to reduce emissions. Additionally, it is crucial to manage the proper disposal of legacy ash in these plants to ensure that farmers like Maniram can return to their livelihoods and continue farming, rather than being forced to work as daily wage labourers.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

More than 180 houses demolished in Bhaukhedi, no compensation offered

Farmers prevent soil erosion through bamboo plantation

Will Pithampur become another Bhopal? Toxic waste disposal spark fears

Eclogical impacts of linking Parbati, Kalisindh, and Chambal Rivers

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.