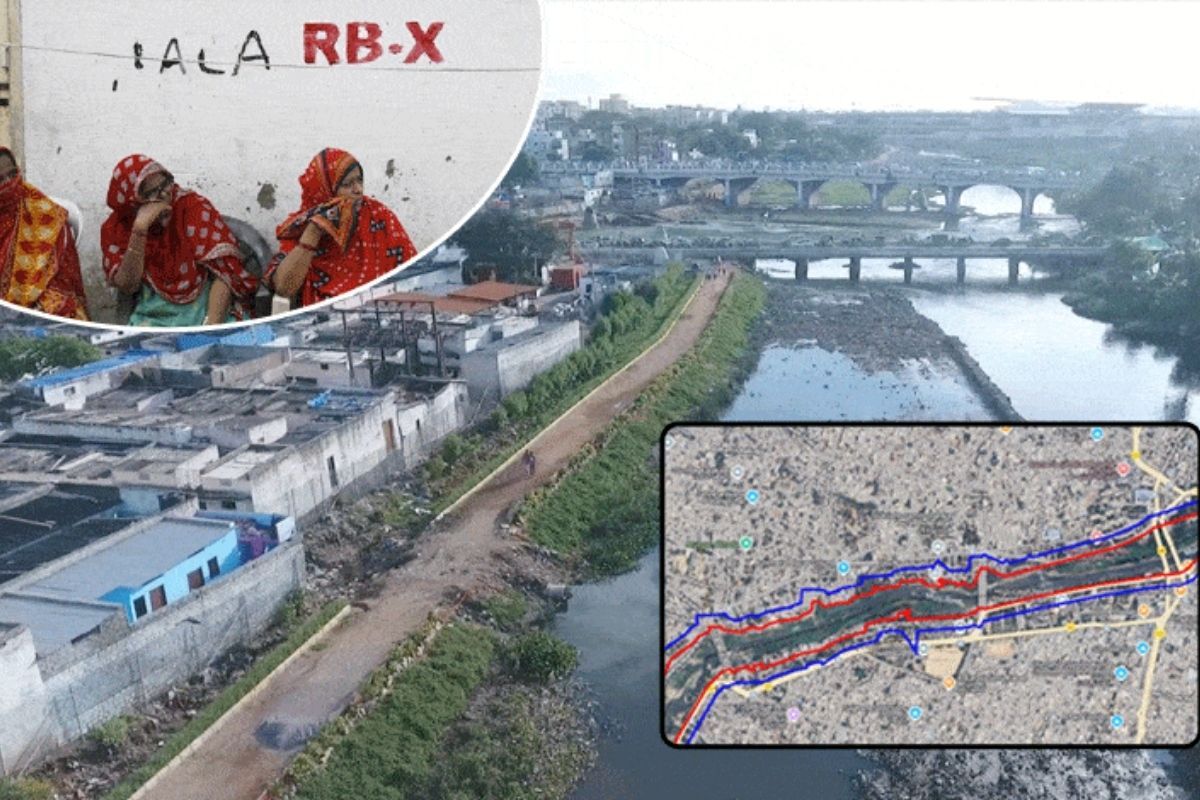

The Telangana government’s Musi Riverfront Development Project, a transformative urban revitalization plan for the Musi River, has sparked controversy and unrest among residents. While the government envisions a riverfront like London’s Thames, with IT towers, commercial spaces, and entertainment zones, the proposed beautification and buffer zone construction come at a steep social cost. Thousands of residents, including those with long-standing housing and legal titles, face uncertainty and displacement.

Demolitions and relocation plans

On October 1, over 160 houses in Shankar Nagar, Malakpet, were demolished without prior notice, displacing hundreds. Officials promised resettlement in two-bedroom apartments about two kilometres away. However, many families are concerned about the reduced space and loss of community ties. The Telangana administration pledged 15,000 housing units for the evictees, but residents are skeptical. Many were reportedly coerced into accepting relocation terms under the threat of losing resettlement eligibility.

Demolition of Houses in Shankar nagar for Musi Rejuvenation.#musiriver pic.twitter.com/QBmwUizPcm

— Nawab Abrar (@nawababrar131) October 28, 2024

Local opposition claims the riverfront project could displace 100,000 people. Government surveys identify around 15,000 households in the river’s buffer zone and riverbed, but activists argue the number is higher. Nearly 100 residents obtained a High Court stay order, challenging the forced relocations and questioning the legality of demolitions without due process.

Costly project lacks transparency, impacts poor

The Telangana government’s 2024 development blueprint, “Telangana Growth Story,” highlights the Musi project’s scope, including multiple bridges, commercial outlets, and public spaces. However, with a projected cost of ₹1.5 lakh crore, the lack of a detailed project report (DPR) raises questions about feasibility and fiscal responsibility. The opacity of these plans, including surveys and budget allocations, has heightened public mistrust. Activists contend that the project risks turning urban spaces into profitable real estate at the expense of the poor.

The identified resettlement sites’ distance from the residents’ original communities exacerbates the challenges of displacement by severing social, economic, and educational ties. Mujahid, a former driver in his sixties, whose family of 17 lived in a four-room home, has been asked to relocate into a two-bedroom unit, raising concerns over space and housing stability. For ragpicker families in Shivaji Bridge, where 120 households live, resettlement could mean losing access to their livelihoods without clear plans or notice.

After civil society criticism, the Telangana government offered each displaced family a relocation grant of ₹25,000 and a livelihood loan of ₹2,00,000 (with ₹60,000 repayable by beneficiaries). Officials established a Consultative Livelihood Support Committee to assist the evictees, but critics note the lack of a cohesive, transparent plan. Many residents want to resettle within 2-3 kilometres of their original homes, in line with the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Act, 2013.

Environmental and infrastructural impact

The Musi River’s ecological degradation due to unchecked sewage disposal remains a critical issue. Reports indicate only 38% of Hyderabad’s daily sewage is treated, with untreated waste directly polluting the river.

Environmental activists argue that removing riverbed encroachments won’t reverse the river’s decay, pointing to longstanding city encroachments and infrastructure projects that impede Hyderabad’s natural hydrological systems. Critics call for adherence to Government Order No. 111, which restricts construction near vital reservoirs to protect Hyderabad’s water resources.

Opposition demands transparency, protect poor

The Musi project has intensified Telangana’s political landscape. Opposition parties, including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), accuse the Congress government of overlooking the poor’s interests. BJP leaders organized a “Maha Dharna” in solidarity with affected families, voicing readiness to “protect the poor” from unjust eviction. Meanwhile, local leaders demand transparency regarding the projected expenses, contrasting the Musi project’s costs with successful riverfront projects like Sabarmati and Namami Gange.

Some Telangana ministers defend the project, asserting it aims to rejuvenate a polluted river. However, activists and urban planners urge authorities to prioritize a transparent, community-centred approach, warning that an aesthetic makeover cannot compensate for sustainable urban planning. They advocate for comprehensive environmental and social rehabilitation rather than displacing vulnerable communities.

As the Telangana government proceeds, displaced communities along the Musi River demand fair compensation, transparency, and inclusion in decision-making processes for an equitable development project.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

Govt shelves elephant census, population drops 20% in 5 years

Wildlife SOS mourns passing of Suzy, 74, oldest rescued Elephant

Asian Elephants display complex mourning rituals similar to humans: study

Asian Elephant populations threatened by rapid ecosystem decline

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.