Extreme heat is not only uncomfortable, but it is deadly. Heat waves are expected to become more frequent, more severe, and longer with climate change. Projections of heat stress based on temperature only underestimate the problem, according to two recent studies.

Humidity intensifies future heatwaves

The reason is that humidity – the amount of moisture in the air – plays a big role in how hot the temperature feels. Humid air that is saturated with water vapour interferes with the body’s ability to cool itself through sweat. Very little research has studied how humidity will affect extreme heat events with climate change, but two new studies suggest that humidity may worsen the effects of future heat waves.

A deadly heat wave hits the plains of northern India, and some 20 million people died from persistent “wet bulb” temperatures of over 35°C (95°F). That’s the plot of “The Ministry for the Future,” Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel about climate change. The scenario is fiction, but similar temperatures have been briefly recorded in the real world. And as the globe heats up, they will become more common.

While the human body has a remarkable ability to get rid of excess heat, previous research suggests that even a strong, physically fit person resting in the shade without clothing and unlimited access to drinking water would likely die within hours of readings of “wet bulb” of more than 35° Celsius: equivalent to a heat index of 160° Fahrenheit.

This is because sweat cannot evaporate quickly enough in moisture-saturated air, resulting in the body overheating.

High humidity

However, even at a wet-bulb temperature (WBT) of 32° Celsius, these same physically fit people are unlikely to be able to engage in normal outdoor activities. And anything they do in temperatures between 20 and 30° Celsius and with high humidity can be dangerous to human health.

“High wet-bulb temperatures cause people to overheat, suffer heat stroke or, in extreme cases, death. When wet-bulb temperatures are high, people won’t be able to engage in strenuous outdoor activities for extended periods, such as construction, farming, and sports,” said Radley Horton, a Columbia University research scientist and co-author of the study ‘Lamont-Doherty‘.

They found that as the planet warms, the heat index increases more than the air temperature. In other words, how hot you feel increases faster than the rise of mercury in thermometers. This means that looking at temperature alone underestimates how much people will suffer from extreme heat as climate change proceeds.

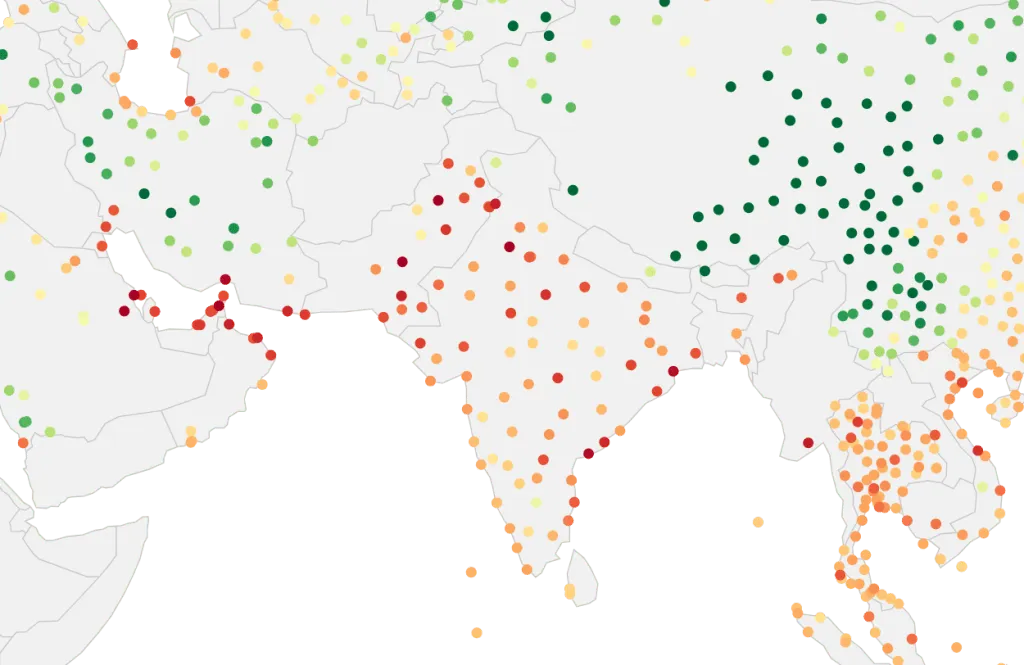

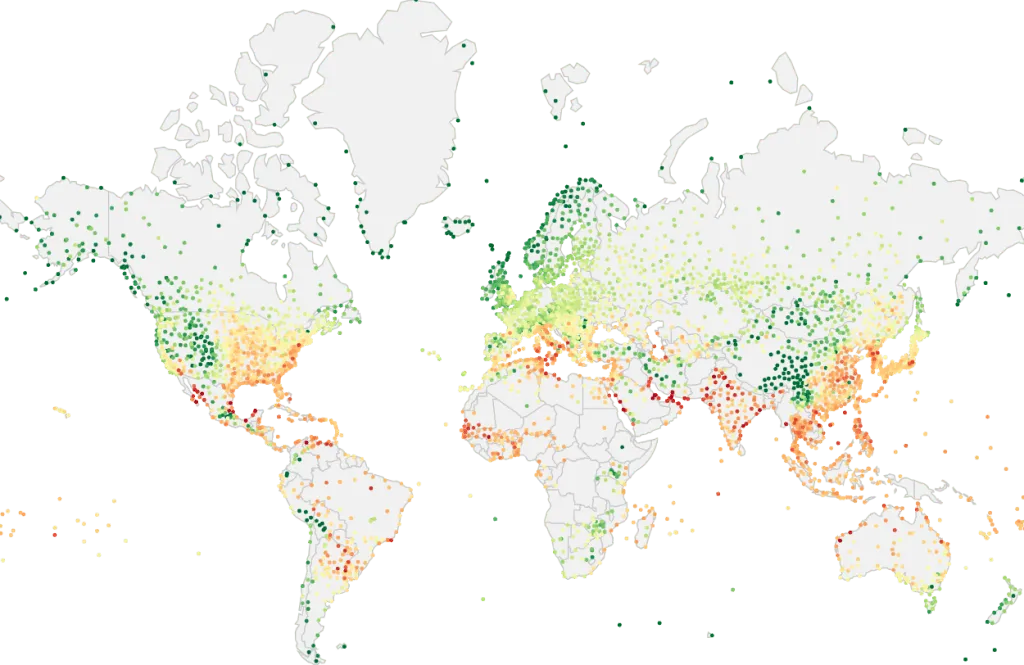

The analysis shows that the increase in the heat index will amplify the effects of heat waves in the tropics, particularly in Southeast Asia.

If carbon emissions are high or moderate, the gap between the heat index and air temperature will widen over the course of the 21st century. But if we are able to reduce carbon emissions dramatically in the coming decades, the rate of heat won’t be too much of a problem, according to the researchers.

What is wet bulb temperature?

The wet bulb temperature (WBT) is a special measurement that helps us understand how hot and humid it is. It is measured with a thermometer covered with a cloth soaked in water and exposed to the air. When the humidity is 100%, the wet bulb temperature is the same as normal air temperature. But when the humidity is lower, the wet bulb temperature is cooler because of the way water evaporates.

The WBT tells us the lowest temperature that the air can reach by evaporating water under current conditions. It’s like the freshest air can get naturally. If the humidity is high, it means that there is a lot of humidity in the air and the WBT will be close to normal air temperature. But if the humidity is low, the WBT will be lower than the normal temperature because evaporation cools the air.

When it is very hot and the WBT reaches 32 °C (90 °F), even people used to the heat cannot carry out outdoor activities comfortably. It becomes a challenge to stay outside for a long time. At 95 °F (35 °C), which feels like 160 °F (71 °C) because of the humidity, people can only survive for up to six hours in such extreme conditions.

Therefore, wet bulb temperature is a crucial tool in understanding how heat and humidity can affect our bodies. When it is extremely hot and humid, it is essential to take precautions and avoid being outside for long periods of time to stay safe and healthy.

When do wet-bulb temperatures get dangerous?

Attention is often focused on a critical point called the “threshold” wet bulb temperature (WBT) for humans. This is the temperature at which a healthy person can survive for only six hours. This threshold is generally considered to be around 35°C, which is equivalent to an air temperature of 40°C with a relative humidity of 75%. For example, during the UK peak on July 19, the wet bulb temperature was about 25°C with a relative humidity of about 25%.

Our bodies usually stay cool by sweating, but once the wet bulb temperature rises above a certain point, usually 35°C, our sweating can no longer cool us down. As a result, our body temperature begins to rise, and this becomes a limit to our ability to adapt to extreme heat. If we can’t escape such conditions, our body’s core temperature can go beyond what our body can handle and our organs could start to fail.

While the often-mentioned threshold is 35°C, recent research suggests that the actual limit our bodies can withstand could be lower, around 31.5°C. This means extreme heat could be even more dangerous than we previously thought. If this new finding is accurate, many more people around the world would be exposed to deadly combinations of heat and humidity.

Projected increase in oppressive Heat

A second study, published in Dec last year in Environmental Research Letters, used a different measure known as the wet-bulb temperature to assess the combined effects of temperature and humidity.

The second group of researchers adopted a comparable methodology to the first group, projecting future wet-bulb temperatures worldwide by utilizing climate change models’ air temperature, humidity, and surface pressure data. Additionally, their findings were even more distressing.

They found that by 2080, wet-bulb highs that now occur only once a year could hold 100 to 250 days of the year in the tropics. In other words, what are currently the most oppressive days will become the norm. Even at mid-latitudes, wet bulb highs that now occur once a year can occur 25 to 40 days a year.

By the 2080s, wet-bulb temperatures of 32°C could occur 1-2 days a year in the southeastern United States, 3-5 days a year in parts of South America, Africa, India, and China. Overall by the 2070s, the planet will see an annual figure of 750 million people a day exposed to these conditions in a high-carbon scenario and 250 million people a day exposed if carbon emissions are moderate.

Wet-bulb temperature and deadly heat stress

With a wet-bulb temperature of 32°C, sustained physical labour becomes impossible. Wet-bulb temperatures that exceed body skin temperature of approximately 35°C are potentially dangerous even if the person is resting. At least, that’s what scientists think – we don’t really know what happens to people under such conditions because they’re so rare in today’s climate.

But under a high-emissions scenario, the researchers estimate that there could be more than a million people a day exposed to wet-bulb temperatures of 35°C by the 2070s.

Fortunately, if carbon emissions are low or moderate, wet-bulb temperatures of 35°C will be potentially rare.

However, according to co-author Radley Horton, a climate scientist at Lamont, “Many people will succumb to heat-related illnesses well before reaching the wet-bulb temperature of 90 degrees Fahrenheit.” During recent heat waves, wet bulb temperatures ranging from 29 to 31°C have resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of individuals.

“In the coming decades, heat stress may prove to be one of the most felt and directly dangerous aspects of climate change,” according to the researchers. They call heat stress “a potentially transformative risk factor for humans.” The burden will be high in regions where people work outdoors and don’t have access to air conditioning, safe water and medical treatment.

Why extreme heat is so deadly

Extreme heat is a deadly force that poses greater dangers than many people realize. As climate change intensifies, extreme heat can have deadly consequences, often dismissing it as an inconvenience or discomfort to combat with air conditioning. From its ability to quickly overwhelm the human body to its role as a major driver of weather-related disasters, understanding the true threat of extreme heat is crucial to safeguarding lives and shaping sustainable futures.

At the heart of the danger is the deceptive subtlety of extreme heat. Unlike more visible natural disasters, such as hurricanes or earthquakes, heat waves can be insidious, slipping through daily life until they become an overwhelming force. The lethal impact of heat on the body is often underestimated, especially by those in good physical condition. But even the healthiest of people can fall victim to its relentless power.

Extreme heat is similar to having a loaded gun pointed directly at people. It puts enormous pressure on the human body, particularly the heart, leading to heat-related illnesses such as heat stroke, dehydration, and heat exhaustion. For vulnerable people with pre-existing health conditions or taking certain medications, the risks are even higher. Heat is a predatory force, attacking the most susceptible and inflicting devastating consequences.

Recent tragic incidents serve as grim reminders of the lethality of extreme heat. In 2021, a young California family sought solace on a hiking trail on a hot day, but ended up losing their lives due to scorching temperatures. The incident highlights that even outdoor enthusiasts can fall victim to the dangers of extreme heat, underscoring the importance of recognizing its deadly potential.

Heatwaves: Too hot to handle?

A crucial question is how the climate crisis and rising temperatures are related to wet bulb temperature (WBT) extremes. A study conducted last year revealed that for every 1°C of average warming, the maximum WBT in tropical regions would also increase by 1°C. This implies that if we limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, we can prevent much of the tropics, where 40% of the world’s population lives, from reaching the 35°C survival limit.

The climate crisis is exacerbating heat waves at an alarming rate, much faster than any other type of extreme weather. Scientists estimate that the climate crisis has made heatwaves like the one experienced in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely. It is becoming increasingly clear that questioning whether such shocking heat waves could have occurred in a pre-industrial climate is becoming irrelevant.

Instead, the focus is shifting to finding solutions to deal with the growing impact of heat waves on people’s lives. As the lethal combination of high humidity and high temperature becomes more prevalent, some places may become too hot to support human habitation, requiring migration routes to help millions of people relocate to safer areas far away from their regions of origin. This issue is becoming more urgent as the world grapples with the growing threat of extreme heat waves.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.