Read in Hindi | Balram Patidar, a resident of Mungawali village in Sehore district of Madhya Pradesh, artificially inseminated his cow using sorted sexed semen technology. This technology ensures that the calf born to the cow is female.

After Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh is the second state in India where a laboratory has been set up for Rs 47.50 crore under the National Gokul Mission to prepare sorted sexed semen. American companies have patents on this technology. India is spending Rs 800 per dose on procurement and is subsidizing farmers to provide one dose for Rs 100. The objective of this scheme is to produce only female calves and to prepare an improved breed of cows.

In our report, we have tried to understand the status of this program on the ground and why is there a need to determine the sex of the calf growing in the womb of a cow with the help of technology.

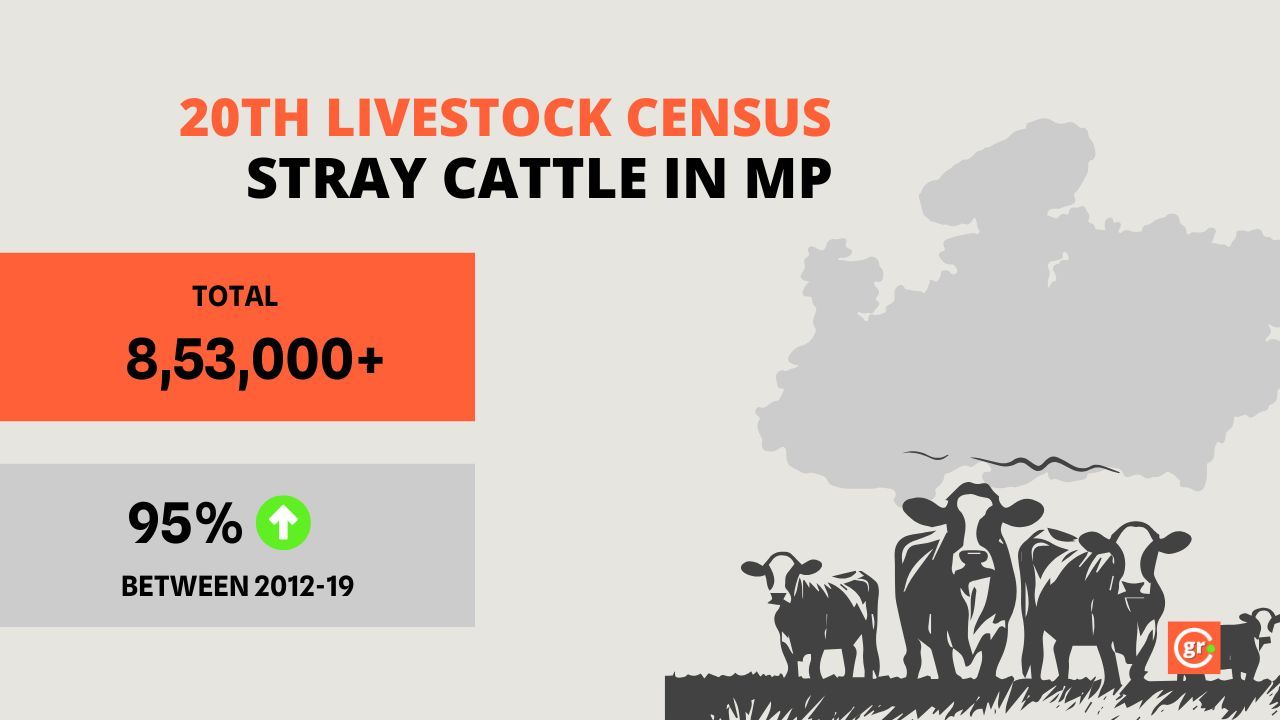

Stray cattle crisis

The number of stray cattle is constantly increasing in India. According to the 20th Livestock Census conducted by the Ministry of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India, there are more than 8 lakh 53 thousand stray cattle in Madhya Pradesh. Between the years 2012 and 2019, the number of stray cattle in the state increased by 95 percent.

Cow slaughter has been banned in the state since 2004, so stray cattle roaming on the roads are causing road accidents or destroying the crops of farmers. The government is rapidly constructing cow shelters in Madhya Pradesh, but the number of cow shelters is very low in proportion to the speed at which the number of cows being abandoned by farmers is increasing.

‘What is the use of bulls now?’

Dr Deepali Deshpande, in charge of the Central Institute of Semen in Bhadbhada, Bhopal, offers a perspective on the changing agricultural landscape. “The traditional role of bulls and bullocks in farming has fundamentally transformed,” she explains.

“Mechanization and technological advancements have rendered these animals increasingly obsolete, leading to their abandonment and proliferation as stray cattle on our roads.”

While addressing the potential of sorted sexed semen technology, Dr. Deshpande cautions against a narrow interpretation. “This isn’t merely about producing female calves,” she emphasizes. “Our broader mission is genetic improvement—creating robust, high-yield dairy breeds that offer tangible economic advantages to farmers.” By strategically controlling the cattle population and enhancing milk productivity, this technology could provide a sustainable solution to the growing challenge of stray cattle and agricultural economic distress.

Sehore on mission mode

Dr. Ashok Bhadauria, Deputy Director of Animal Husbandry and Dairy Department in Sehore, speaks with determined optimism about the technological intervention. “We are strategically positioning ourselves to revolutionize cattle breeding,” he declares.

“Our targeted goal is to achieve comprehensive insemination of approximately 1 lakh cows through sorted sexed semen technology by March 2025.”

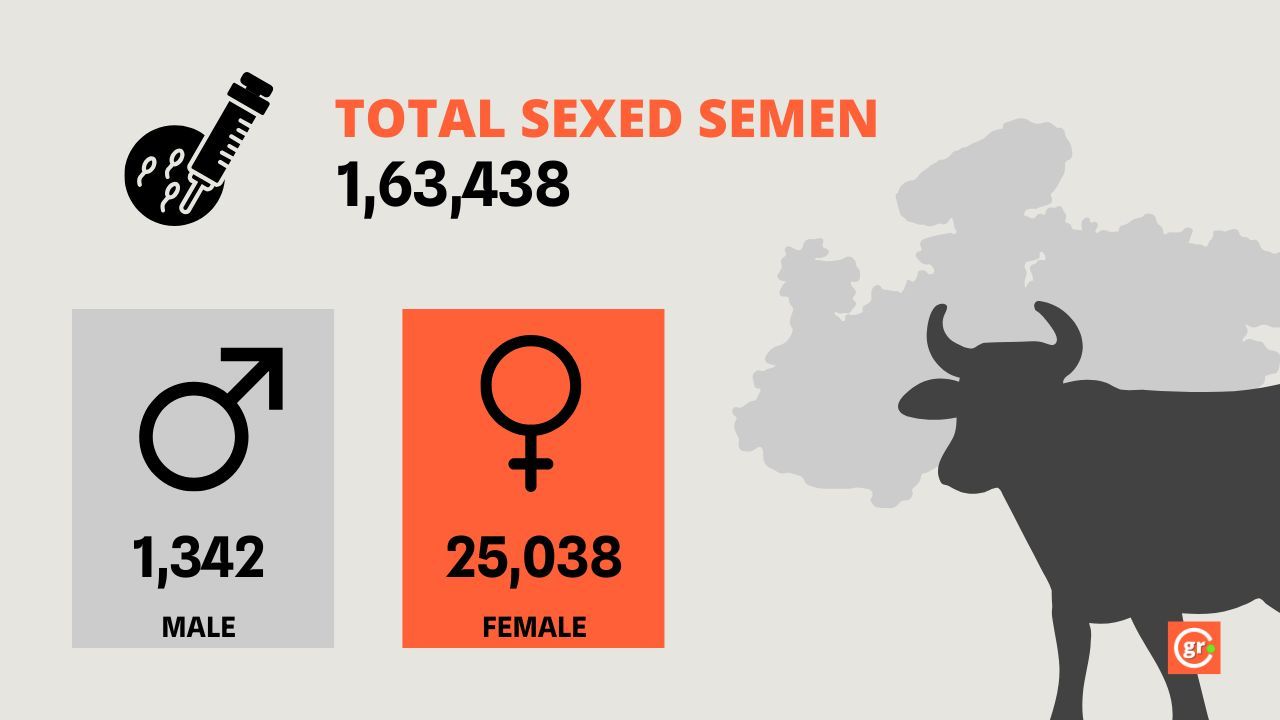

According to data from the Central Semen Institute Bhopal, till October 15, 2024, 1 lakh, 63 thousand, 438 cows have been inseminated using this technique. Of the total 26,400 calves born, 25,038 are female.

Balram Patidar’s experience reveals the complexity of technological implementation. While he successfully obtained a female calf through sorted sexed semen, his father Shaligram Patidar remains sceptical. “The technological intervention has fundamentally altered our traditional cattle lineage,” he laments.

“Generations of our cows were hornless and consistently black. This new calf displays unexpected characteristics—prominent horns and an ambiguous breed profile that challenges our generational breeding expectations.”

Dr. Deepali Deshpande explains such variations. “These inconsistencies often stem from improper artificial insemination techniques,” she explains. “There’s a critical knowledge gap among farmers regarding sorted sexed semen technology. Understanding the precise breed and characteristics of the semen straw is paramount.”

She elaborates on the technological specifics:

“Each sorted sexed semen straw is distinctively white, accompanied by colour-coded tags indicating the specific breed. These tags serve as a crucial reference point, enabling farmers to track and understand the genetic lineage of their insemination process.”

However, field investigations reveal a stark implementation challenge. Several veterinarians admit to not consistently providing these critical identification straws or accompanying documentation. Their rationale—a perceived lack of farmer diligence in preserving such technical materials.

Dr Bhadauria counters these concerns by highlighting technological tracking mechanisms. “All animal insemination data is systematically uploaded on the Bharat Pashudhan App,” he emphasizes. “This digital platform allows precise tracking of cattlekeeper details and corresponding semen breed information.”

Proponents of sorted-sexed semen technology advocate for a long-term perspective. They argue that comprehensive breed improvement will materialize after three generations, ultimately producing high-yield dairy cattle.

This raises a critical question: How does sorted sexed semen differ from conventional artificial insemination in breed development?

Dr. Deshpande provides a compelling differentiation. “Traditional artificial insemination follows an unpredictable generational pattern,” she explains.

“A farmer might receive a male calf one year, a female the next, creating an inconsistent breeding cycle. Sorted sexed semen technology strategically ensures female calf production, accelerating the timeline for developing advanced cattle breeds with remarkable efficiency.”

Veterinarians are facing problems due to low conception rate

The sorted sexed semen technique confronts a significant challenge: a mere 35% conception rate. This low success probability means veterinarians must repeatedly attempt insemination, contrasting sharply with the more reliable conventional artificial insemination methods.

Veterinary practitioner Lokendra Mewada, working as a Maitri-Gausevak in Sehore, candidly articulates the professional and emotional toll. “The reproductive uncertainties with sorted sexed semen create a complex web of challenges,” he explains.

“When cows struggle to conceive, farmers’ frustrations rapidly transform into criticism, directly impacting our professional credibility and reputation.”

Mewada further elaborates on the consequences: “Repeated unsuccessful insemination attempts not only compromise the cow’s reproductive health but also escalate farmers’ financial burdens. Each failed attempt necessitates additional medical interventions, creating a cycle of economic strain.”

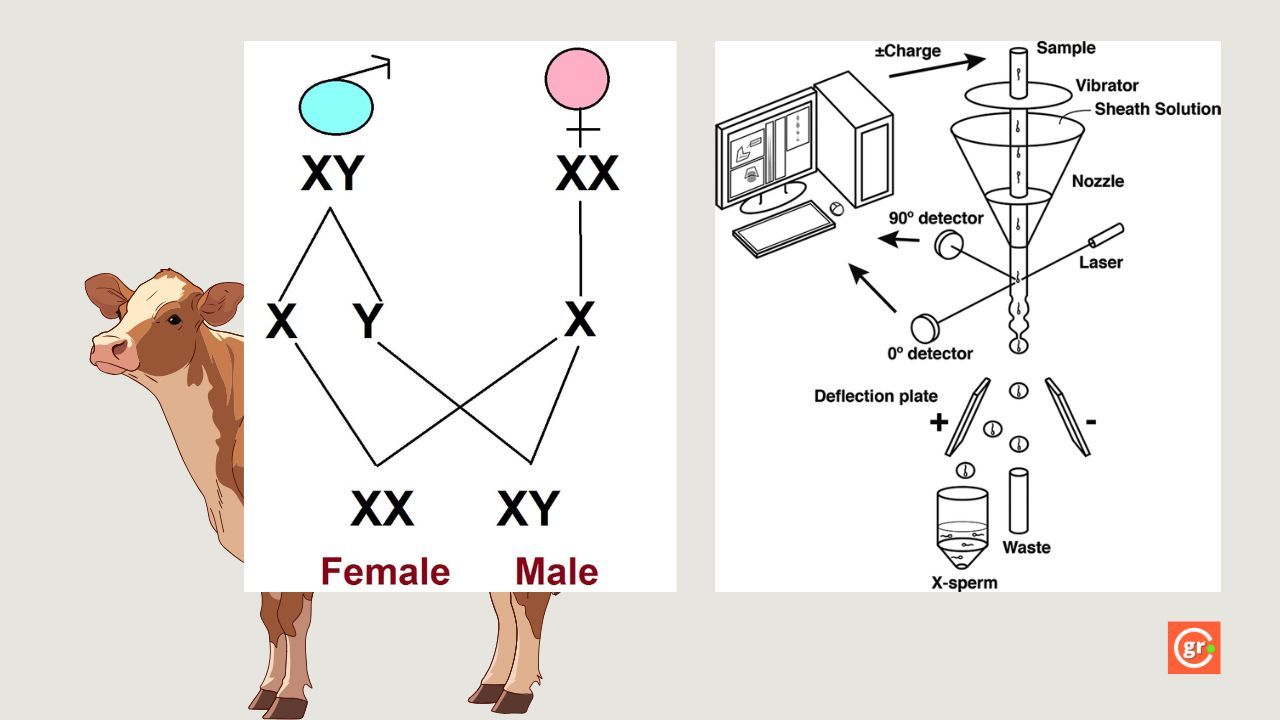

The scientific root of this challenge lies in the chromosomal sorting process. Separating the X and Y chromosomes fundamentally compromises sperm viability and motility. This technological intervention inadvertently reduces the number of viable sperm compared to conventional semen, directly affecting conception probabilities.

Dr. Deepali Deshpande offers a perspective on mitigating these challenges. “This technology demands precision and selectivity,” she emphasizes.

“We must strategically apply sorted sexed semen exclusively to physically and gynecologically robust cows. The animal’s holistic health is the foundational determinant of successful conception and subsequent calf development.”

She critically observes that many veterinarians are not adhering to established protocols. “Inconsistent implementation undermines the entire technological intervention,” she warns.

Ground-level investigations reveal a disturbing pattern of experimental approaches. Multiple farmers reported instances where veterinarians or trainees employed unconventional methods, including simultaneous multiple sperm injections—a practice that deviates from recommended scientific protocols.

Dr Ashok Bhadauria acknowledges the systemic constraints while maintaining an optimistic stance. “Sehore district presents vast geographical and resource challenges,” he admits. “Nevertheless, our commitment remains unwavering. We are determined to successfully implement this technology across one lakh cows by March 2025.”

Is it tampering with the natural order?

Cow’s eggs inherently contain X chromosomes, while bull’s sperm carries both X and Y chromosomes. Typically, an X-X combination results in a female calf and an X-Y in a male. Sorted semen technology disrupts this delicate biological balance by selectively removing Y chromosomes, artificially predetermining female offspring—a stark intervention in nature’s reproductive randomness.

In India, the cow transcends mere agricultural significance, embodying complex religious and political symbolism. While indigenous breeds like the Desi cow hold sacred status, their limited milk production creates an economic paradox. This technological intervention emerges as a calculated response, aiming to enhance breed quality, elevate milk yields, and incrementally improve farmers’ economic prospects.

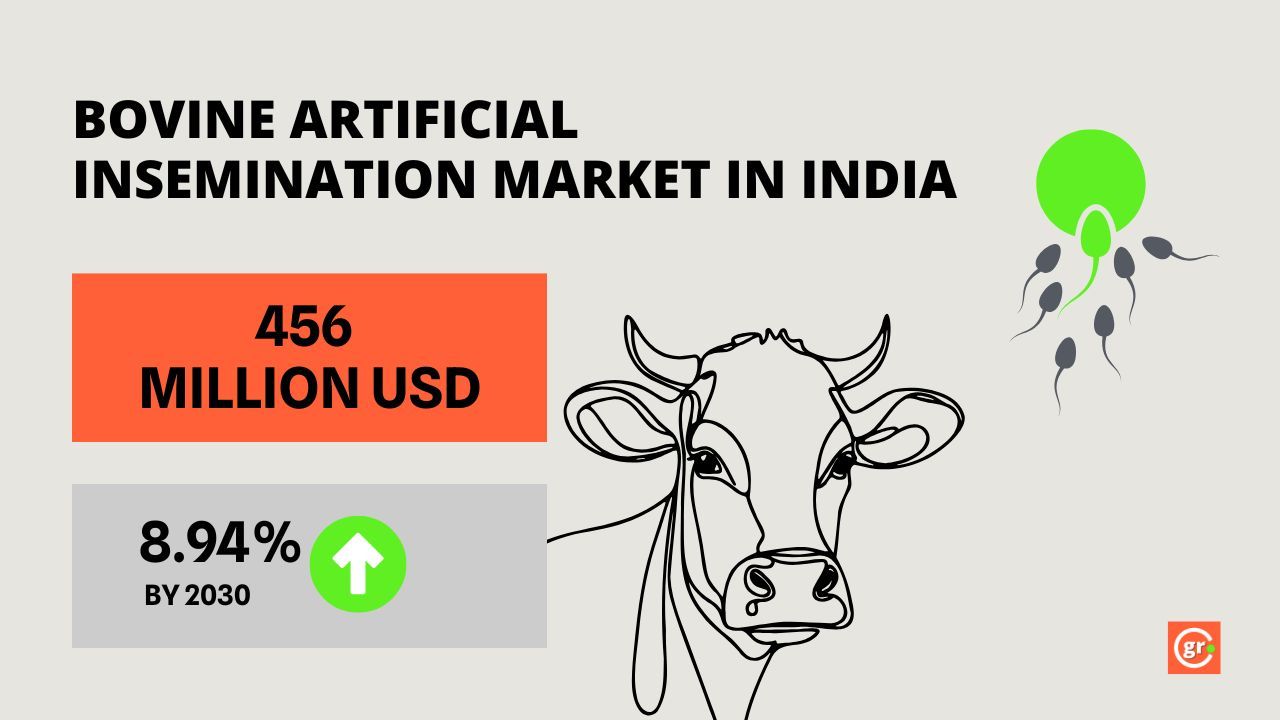

The proliferation of sorted sexed semen technology reveals a profound transformation—where reverence increasingly intersects with commercial pragmatism. By prioritizing profit-driven objectives, this approach potentially reshapes cattle breeding dynamics. The technology’s widespread adoption threatens to dramatically reduce male calf populations, potentially creating systemic dependencies on artificial insemination markets.

India’s cattle artificial insemination market, currently valued at 456 million US dollars, is projected to expand by 8.94 percent by 2030—a testament to the technology’s emerging economic potential.

Shaligram Patidar’s personal narrative encapsulates broader agricultural challenges. He says,

“Dairy farming’s economic viability has dramatically eroded. We’ve witnessed our herd shrink from 21 to just 9 cattle, crushed by escalating fodder costs and stagnant milk prices—a mere 30-35 rupees per litre.”

His testimony underscores the precarious economics confronting traditional agricultural practices, where technological interventions represent both hope and potential disruption.

The administrative implementation of this technology demands rigorous scientific scrutiny. Beyond immediate reproductive objectives, critical long-term considerations emerge: How will these interventions impact genetic diversity? What unforeseen ecological and agricultural consequences might arise from systematically manipulating bovine reproductive patterns?

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

‘Anna Pratha’: crisis for cattle welfare and farmers’ livelihoods

MP farmers battle stray animals, sleepless nights to protect crops

Ground reality of promises to build cow shelters (gaushala) in MP

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.