The Himalayan region, known for its majestic peaks and serene landscapes, has become a hotspot for natural disasters, accounting for 44% of all such events in India between 2013 and 2022, according to the latest State of India’s Environment 2024’ report, released by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).

A staggering 192 incidents, including floods, landslides, and thunderstorms, have ravaged the region, with the recent cloudbursts and torrential rains of 2023 serving as a grim prelude to a more turbulent future.

Kiran Pandey, head of CSE’s Environment Resources Unit, notes an alarming trend in the data, “Disasters are not only becoming more frequent but also increasingly severe, leading to significant loss of life and property.” In just one year, from April 2021 to April 2022, 41 landslide incidents were reported, with the majority occurring in the Himalayan states.

The report sheds light on the long-term damage inflicted upon the upper Himalayas. Rising surface temperatures have led to a rapid melting of glaciers, with the Hindu Kush Himalayas experiencing a 65% faster loss of glacier mass.

Glacier loss rates have increased

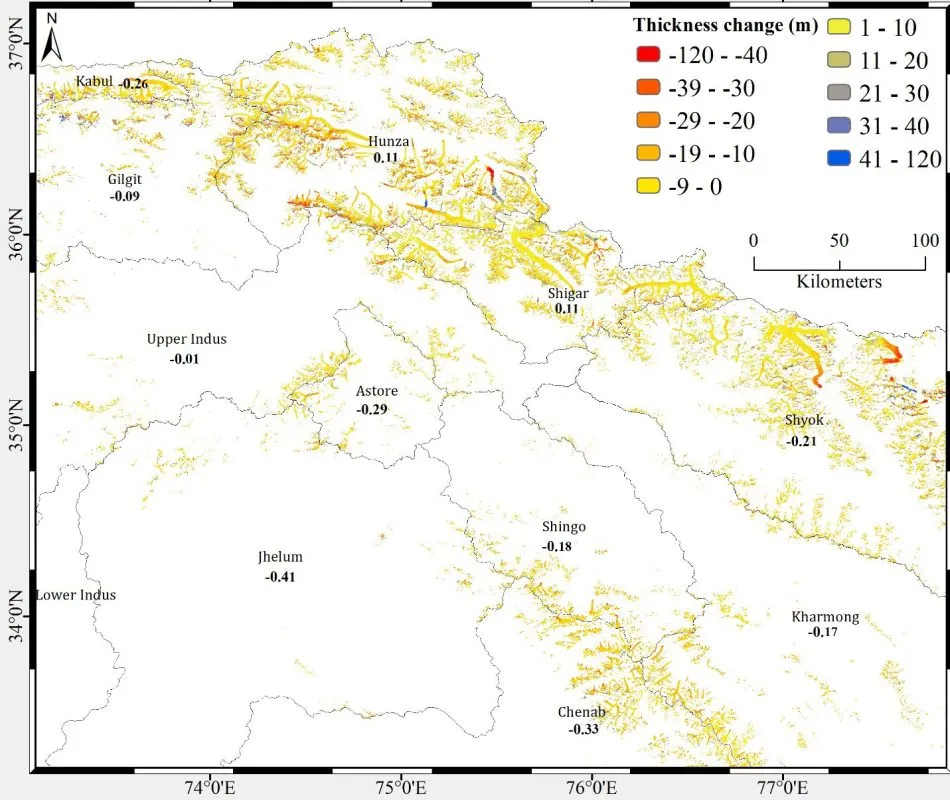

The ICIMOD study reveals that glaciers in the region lost 0.28 metre of water equivalent per year during 2010-19, a stark increase from 0.17 m we per year in the previous decade. Even the Karakoram Range, previously considered stable, has shown a decline, losing 0.09 m per year in the same period.

According to research conducted by ICIMOD (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development), there were inaccuracies in estimating glacier mass changes in the Indus basin due to assuming a constant density of 850 kg/m3. This led to errors ranging from -0.20 to +0.09 meters of water equivalent per year (m w.e.a-1) across the region. The mistake primarily occurred because lower density values (600 kg/m3) were assumed for areas with steep slopes exceeding 20° or 25°.

Examining the entire Indus basin, it was noted that glaciers in the northwest were experiencing significant mass loss. Similarly, glaciers in the southern Himalayan regions such as Chenab, Jhelum, and Ravi were melting rapidly, albeit not contributing substantially to river flows due to their smaller coverage area. The combined mass loss from these glaciers had a minor impact on rising sea levels.

Izabella Koziell, ICIMOD’s deputy director general, warns of the catastrophic implications: “The glaciers are a critical part of the Earth system, and with two billion people depending on their water, the loss of this cryosphere could have devastating consequences. Immediate action is required to avert disaster.”

Extreme climate challenges

The ‘State of India’s Environment 2024’ report also presents a stark picture of the Himalayan region’s vulnerability to climate change. The rapid melting of glaciers is a clear indicator of the crisis, with a 65% increase in mass loss from 2000-2009 to 2010-2019.

The trend is set to continue, with projections suggesting that the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) glaciers could lose 30 to 50% of their volume by 2100 if global warming persists between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius. The expansion of glacial lakes and the potential tripling of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) pose a significant transboundary risk, impacting countries beyond their origins.

The report also notes an uptick in extreme weather events, driven by a combination of slow-onset processes like sedimentation and erosion, and fast-onset hazards such as floods and GLOFs. These events are becoming more frequent and intense, complicating disaster management efforts.

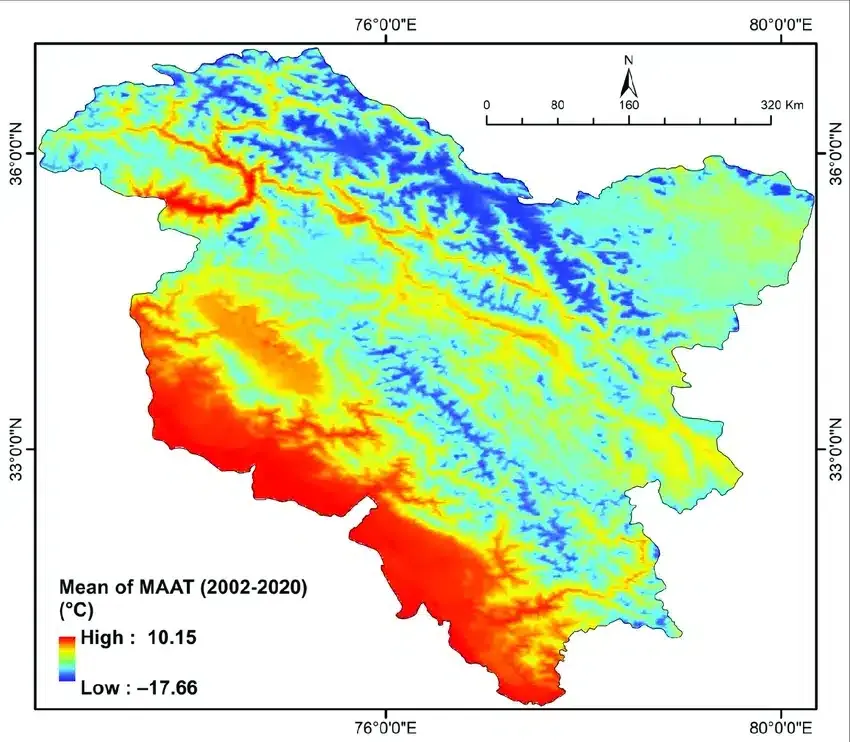

Moreover, the mean temperature across the HKH is rising at an average of 0.28 degrees Celsius per decade, with higher elevations experiencing even greater warming rates. While attributing specific events to climate change remains challenging, the consensus among scientists is that human-induced global warming is the primary cause of these shifts in the cryosphere.

Melting ice forms more lakes

The melting ice has led to the formation of numerous glacial lakes, with the count in Uttarakhand and east of Himachal Pradesh rising from 127 in 2005 to 365 in 2015. The increased frequency of cloudbursts has exacerbated the situation, causing these lakes to overflow or burst, wreaking havoc downstream.

The Himalayas have already lost over 40% of their ice and are projected to lose up to 75% by the century’s end. This dramatic ice loss is causing the vegetation line to shift upwards at a rate of 11 to 54 m per decade. With the majority of Himalayan agriculture dependent on rain, the changing climate poses a severe threat to the livelihoods of the local population and endangers those in the plains reliant on the region’s water resources.

Recent studies highlight the loss of 8,340 square kilometers of permafrost in the western Himalayas between 2002-04 and 2018-20, with significant losses also reported in the Uttarakhand Himalayas. Dr. Miriam Jackson, ICIMOD’s senior cryosphere specialist, warns of the infrastructure damage caused by thawing permafrost, evident in the increasing number of landslides.

Dr. Kalachand Sain, head of the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, advocates for responsible development in the region, stressing the need for guidelines prepared with input from all stakeholders. “To mitigate disasters, we must understand their root causes and engage all parties—governments, locals, experts, journalists—in addressing them,” he asserts.

Evaluating climate impacts

The report urges a comprehensive assessment of climate change’s present and future effects. For permafrost areas, they recommend targeted ground monitoring by HKH nations, prioritizing regions where infrastructure and communities are at risk from thawing.

In terms of glacial research, it’s vital to measure ice thickness, debris cover, internal ice temperatures, and glacier movement rates. There’s a call for enhanced glacier modelling that integrates more closely with hydrological predictions, as well as a deeper understanding of the human influence on glacial changes.

As the mix of water sources feeding rivers shifts, leading to unpredictable flow patterns, policymakers are advised to anticipate and plan for these seasonal variations. Developing strategies to cope with extreme weather is also highlighted as a priority.

The study highlights the need for substantial resources and technological aid for mountain communities to adapt to these environmental shifts. It stresses that climate adaptation policies must be equitable and holistic, taking into account both societal needs and ecological preservation.

Policymakers are urged to consider these findings seriously to develop effective adaptation strategies that can mitigate the impact on ecosystems and the livelihoods dependent on them.

The report advocates for strengthened transboundary collaboration to safeguard the shared legacy of the HKH region, as echoed in the HKH Call to Action by ICIMOD. They note that current cross-border efforts are insufficient, often overshadowed by political and economic agendas rather than focusing on the social and environmental health of the region.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.