Every morning at 7:30, when Ashapuri High School—30 kilometers from Bhopal— starts its day, 15-year-old Deeksha Chaudhary arrives on foot. She sets out early from her home in Rasalpur village, 3 kilometers away. A bicycle, provided under a government scheme, leans rusting and unused at home. The path she takes is familiar but never easy—especially under the harsh April sun.

She studies in class 10. In the heat, the concrete classrooms feel like ovens. 99% of the students in the school are from the marginalised communities (SC, ST, and OBC). One day, she started feeling dizzy in class and fainted. Her friends helped her up. She hadn’t eaten anything at home that morning.

After the incident, she missed four days of school due to fatigue and dizziness. When she returned, she told her teacher that the heat was making her feel sick.

In Barwani, situated near the banks of the Narmada River in Madhya Pradesh, there is a government school where children are forced to sit in the scorching sun with their essential books resting on the dusty floor. At the Government Secondary School in Khajuri Kalan, Bhopal, the capital of Madhya Pradesh, Mansi Yadav’s classroom is a tin shed. When it rains, water drips from the roof and runs down the walls. The floor stays damp. The toilets don’t work. There’s no drinking water.

The government schools operate in abandoned huts, broken houses, or makeshift structures. In many cases, students are forced to attend classes under trees, in temples, or even in community buildings—a conventional concrete roof and wall structure for a classroom is a luxury. Power outages have left classrooms without electric fans, exacerbating the discomfort during heatwaves.

“We don’t feel like studying in summer,” Deeksha says. “But we come anyway.”

On April 8th, the government of Madhya Pradesh, where temperatures soared to nearly 43°C, shifted school hours to 7 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. to avoid the ill effects of rising temperatures. Similarly, the states of Chhattisgarh and Haryana have implemented comparable measures to ensure students’ well-being during extreme temperatures. But, with temperatures soaring and climate risks intensifying, poorly built schools in Madhya Pradesh, without electricity and clean water, are putting students’ health—and lives—on the line.

Science of heat, & consequences on children

“In case of heat stroke, the body temperature can rise to 104°F, or 40°C. It [the temperature rise] can develop slowly or suddenly. If not treated, it can lead to kidney failure or even death,” Dr. Prabhakar Tiwari, Chief Medical and Health Officer, Bhopal, warned.

In schools across Barwani, Chhatarpur, and Khandwa, children attend classes in tin sheds and under open skies. While tin sheds—metal sheet walls—retain the heat from the sun, open skies expose vulnerable children to direct sunlight. Children are more vulnerable to heat than adults. Their bodies heat up faster and take longer to cool down. This makes them more prone to dehydration. heat exhaustion and heatstroke. Babies and young children face the highest risk of heat-related illness and death. Extreme heat also disrupts sleep, concentration, and learning.

“High temperature, dry throat, dizziness, vomiting, weakness, thirst with less urination, and fainting are all signs of heat stroke,” Dr. Tiwari explained. “Immediate medical attention is necessary.”

All government and private hospitals have been asked to remain on alert for the treatment of heatstroke cases. For many children and students, medical attention isn’t nearby. Some schools operate miles from any clinic, leaving students without quick access to medical care during emergencies. In remote areas, even reaching the nearest health center can take hours due to poor roads or lack of transport. Many schools lack first aid kits, so teachers can’t give even basic treatment like oral rehydration, cold compresses, or temperature checks. Without these supplies, they lose valuable time during a heatstroke emergency.

In our previous article, we examined India’s heatwave response, particularly in relation to its impact on children. Are children really safe at home?

Infrastructure issues and impact on learning

At 10:30 AM in April, Ashapuri High School is quiet and still. The ground in front of the main building doesn’t look like a typical plain. The terrain is rough, with stone rocks sticking out. It’s the middle of break time, but the school grounds are empty. Some students sit inside, playing carrom in the classroom.

Mukta Saxena, the principal, sits in her office, signing administrative papers. Her chair is covered with a white towel. She has taught for 32 years, spending the last two years as the principal of the school. “It’s getting harder to work in March and April. Students have exams in February. The result work lasts through March, and then classes start in April. It didn’t used to be this hot in April, but now it feels like May.”

Saxena explains the school’s efforts to beat the heat. “We’ve planted trees around the school to keep it cool. The children helped set up a ‘Navgriha Vatika.’ We put in a water cooler because earlier, we had a water pot, but no one could keep it filled. So, we got a cooler installed.”

When asked if the school was built with extreme weather in mind, Saxena says, “This building was built in 2014. I wasn’t here then, but in my experience, school buildings are built with high ceilings to stay cool when the sun heats them. Also, every classroom has windows for air to flow in and out.”

Despite the efforts, Saxena acknowledges a major challenge: water.

“We don’t have a water supply from the panchayat. We rely on a borewell, but when it fails, it causes problems. Last year, in April, it broke down. It took a week to fix it, and during that time, the children had to rely on the panchayat’s hand pump for water.”

Nearly 100 schools in Barwani district face severe infrastructure problems. A survey by Child Rights and You (CRY) found that over 94% of schools in 13 districts, including Bhopal, lack basic infrastructure such as electricity, functional toilets, and benches. Additionally, more than 8% of schools have no toilets, and 49% have unusable ones.

Broken toilets increase student absences

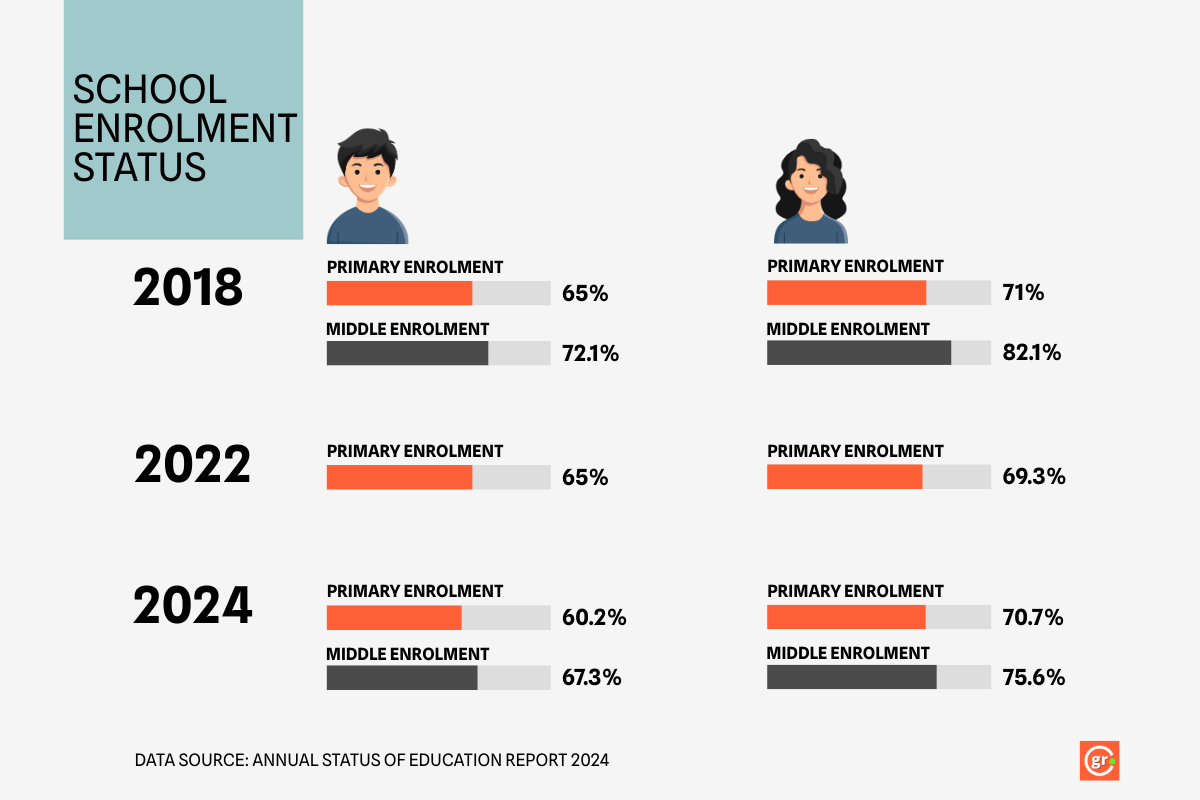

A study found that schools with inadequate sanitation facilities face higher absenteeism rates, particularly among girls, who are often the first to drop out in the face of such hardships. The lack of basic infrastructure, such as toilets and clean drinking water, further exacerbates the vulnerability of students from marginalized communities.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024 highlights this troubling trend, pointing to the sharp decline in government school infrastructure and student enrollment in rural Madhya Pradesh.

Megha Pathak, a teacher at Ashapuri High School, arrives early every day. She is from Bhopal and rides her scooter 30 km to school. One April morning, only six children are in her class, though the class typically had 25 students. Megha sighs and says, “It’s so hot that no child wants to come. Attendance was okay on April 1, but as the days go on, fewer children show up. Most come from far away, and parents are worried about heatstroke.”

She rides back 30 km in the scorching sun at around 1:30 PM. “It’s tough,” she says. “Even with a helmet on, the wind is scorching. In just 40 minutes… I’m drained.” She candidly explains her irritable behavior and her snapping at her children for no reason. “I’ve told them to leave me alone for an hour when I get home.”

Before coming to Ashapuri’s government school two years back, Pathak taught at a private school in Bhopal. Comparing the two experiences, she says, “Private schools have better infrastructure. But our new principal has helped a lot. She got us a water cooler, and that’s a big help.”

For Pathak, the reasons are straightforward: children don’t get enough food and drink enough water. That is true—at least in the case of Ashapuri High School. Every student we conversed with said that either they had missed breakfast or drank just one bottle of water. Sometimes, they said both the statements.

A 2020 study in Nature found that students scored worse during hot school years than in cooler ones.

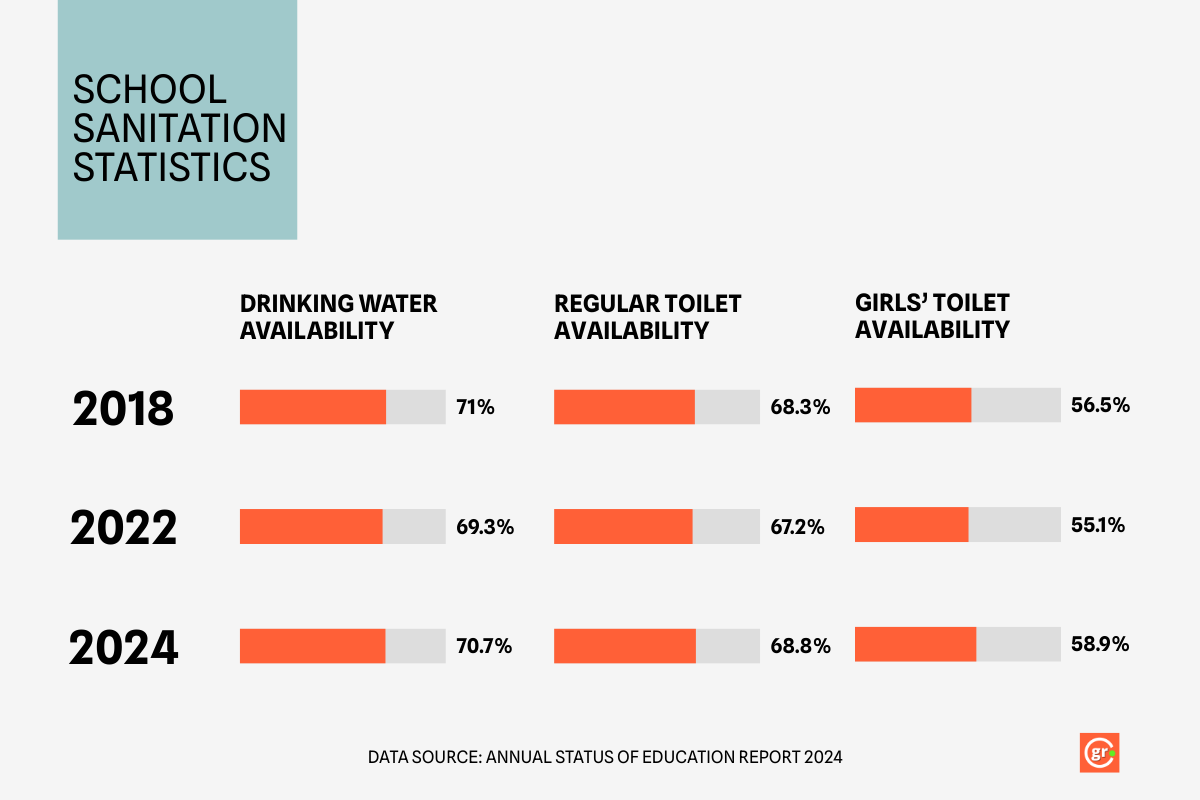

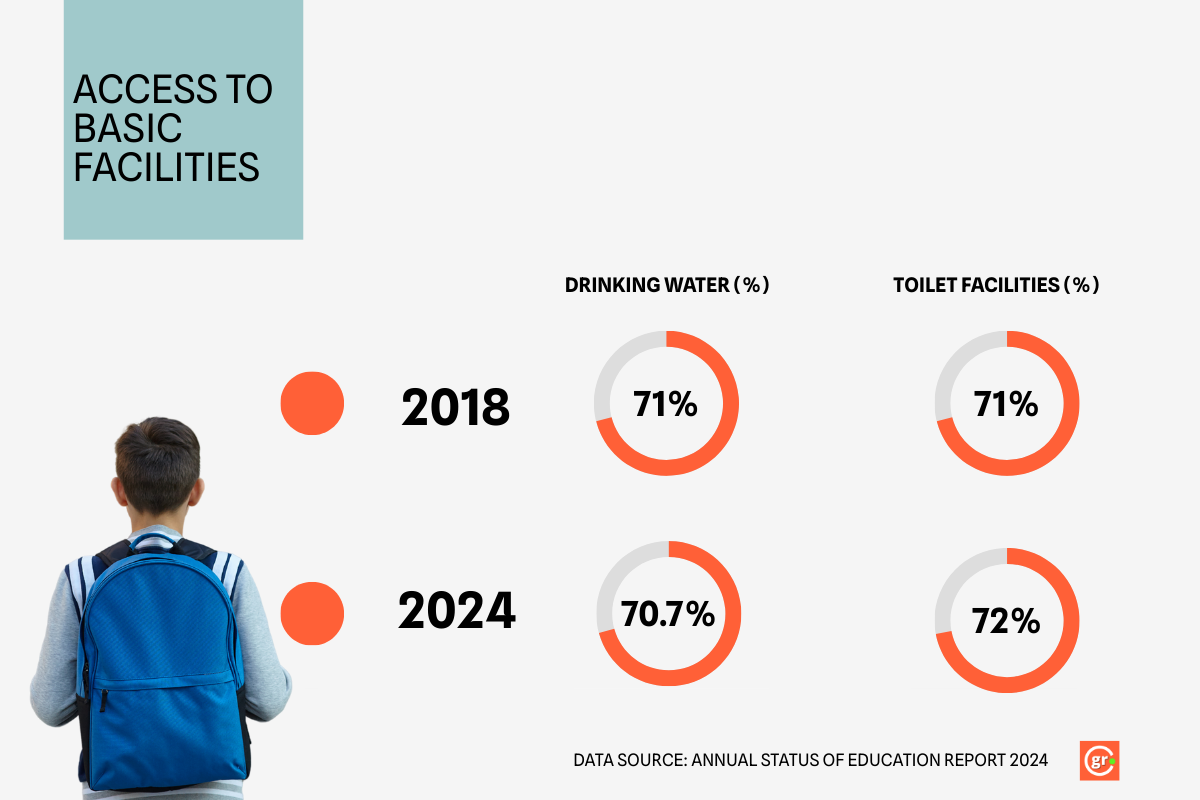

In 2018, 71% of schools had drinking water; by 2024, this had decreased to 70.7%. Toilet facilities followed a similar pattern, dropping and recovering slightly over the years. This slight recovery still leaves a significant number of schools without a basic necessity, especially in the intense summer heat. Without reliable access to drinking water, students are left vulnerable to dehydration and harsh conditions, further compounding the challenges they face in an already under-resourced education system.

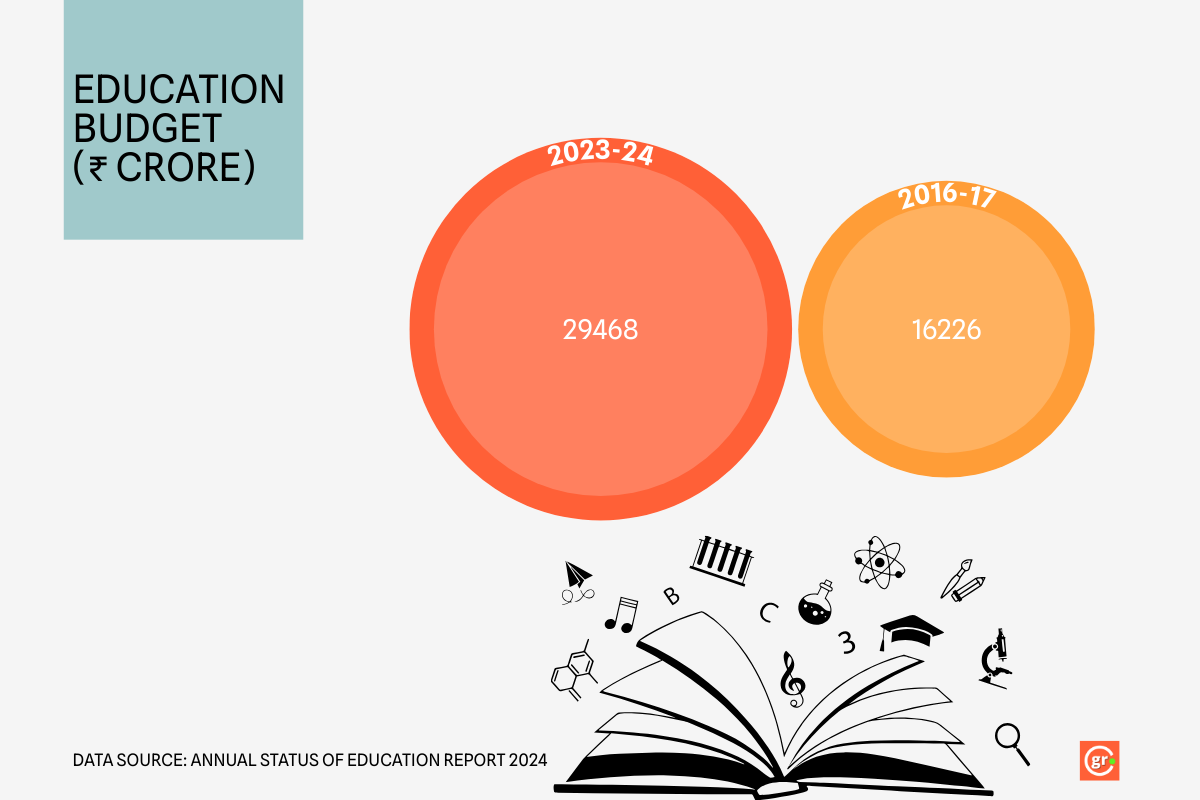

Budget rose, schools still suffer

Despite an 80% rise in the education budget over the past seven years—from ₹16,226 crore in 2016–17 to ₹29,468 crore in 2023–24. Meanwhile, the government’s attention is elsewhere.

While high-end schools like CM Rise and PM Shri receive modern amenities—smart classes, robotics labs, and computer labs—children in places like Barwani still lack basic infrastructure. Out of 82,935 government elementary schools in the state, 36,000 lack boundary walls, leaving children vulnerable.

While hospitals in the state are following the National Action Plan on Heat-Related Illness and have implemented measures such as reserving beds for heatstroke patients, keeping wards cool with fans or coolers, and examining OPD patients for symptoms, the situation in government schools paints a starkly different picture.

ORS zinc corners have been set up in hospitals and health centers, but none exist in schools, where teachers—already overburdened—lack even basic training in handling heat emergencies. “Children, the elderly, and those with health conditions are most at risk,” said Dr. Tiwari, who emphasised immediate steps like moving collapsed individuals to the shade and cooling them with water.

Despite advisories urging people to stay hydrated, avoid exertion in the sun, and use ORS, buttermilk, or fruit juice when sweating excessively, many schools struggle with broken toilets and scarce drinking water.

The teachers at Ashapuri High and in Madhya Pradesh only get leave from May 1 to May 31. If any training happens during this time, they have to attend. “The heatwave continues until June, and we still work through it,” Megha says. “The lights stay on until noon, and then they come back on at 5 PM. We work until 1:30 PM.” She’s also frustrated by the lack of proper facilities for teachers.

The state of Madhya Pradesh was the worst hit in 2024, experiencing 185 extreme weather event days, the highest in India, which challenges the rudimentary infrastructure of schools, essentially impacting the learning of the children in marginalized communities. Heatwaves are no longer rare events—they’re shaping the school calendar. Madhya Pradesh’s early summer break shows how rising temperatures disrupt education. On June 16, schools in Madhya Pradesh will reopen. States need clear guidelines to upgrade school infrastructure for rising heat. But unless classrooms are built for rising heat, this shutdown isn’t a solution.

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Keep Reading

The costliest water from Narmada is putting a financial burden on Indore

Indore’s Ramsar site Sirpur has an STP constructed almost on the lake

Indore Reviving Historic Lakes to Combat Water Crisis, Hurdles Remain

Indore’s residential society saves Rs 5 lakh a month, through rainwater harvesting

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.