- In 2023, scientists project it to be the warmest year on record, with persistently rising levels of greenhouse gases.

- This has resulted in record sea surface temperatures and a significant increase in sea levels, along with a record low in Antarctic sea ice.

- The year has also been marked by extreme weather events causing widespread death and devastation.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has reported that 2023 has broken climate records, with extreme weather events causing widespread destruction and despair.

2023 set to be warmest year on record

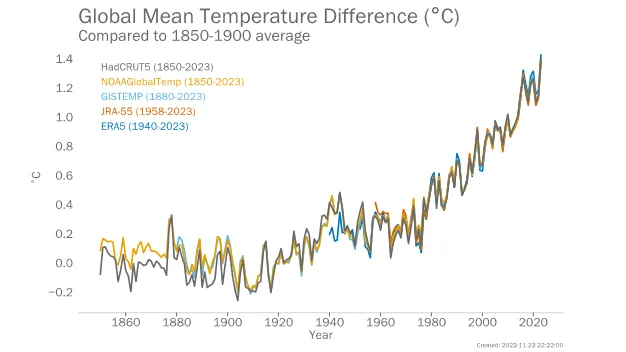

According to the WMO’s provisional State of the Global Climate report, 2023 is on track to be the hottest year ever recorded. Data up to the end of October indicates that the year was approximately 1.40 degrees Celsius (with a margin of uncertainty of ±0.12°C) above the pre-industrial baseline of 1850-1900. The gap between 2023 and the previously warmest years, 2016 and 2020, is significant enough that the final two months are unlikely to alter this ranking.

The last nine years, from 2015 to 2023, have been the warmest in recorded history. The El Niño event, which began in the Northern Hemisphere’s spring of 2023 and rapidly intensified over the summer, is expected to further increase temperatures in 2024. This is because the global temperature impact of El Niño is typically most pronounced after its peak.

“Greenhouse gas levels are record high. Global temperatures are record high. Sea level rise is record high. Antarctic sea ice is record low. It’s a deafening cacophony of broken records,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

“These are more than just statistics. We risk losing the race to save our glaciers and to rein in sea level rise. We cannot return to the climate of the 20th century, but we must act now to limit the risks of an increasingly inhospitable climate in this and the coming centuries,” he said.

“Extreme weather is destroying lives and livelihoods on a daily basis – underlining the imperative need to ensure that everyone is protected by early warning services,” said Prof. Taalas.

Levels of carbon dioxide are now 50% higher than they were in the pre-industrial era, leading to an increase in atmospheric heat. Due to the long lifespan of CO2, we can expect temperatures to continue to rise for many years.

Sea level rise accelerates, ice melts

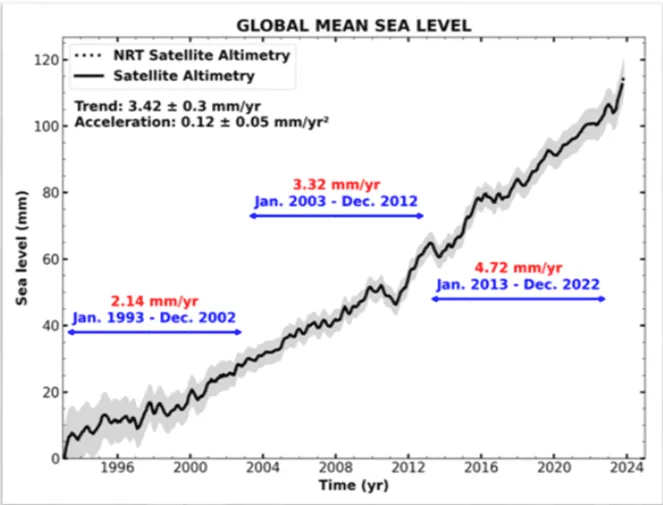

The rate of sea level rise from 2013-2022 has more than doubled compared to the rate recorded in the first decade of satellite records (1993-2002). This is due to the ongoing warming of the ocean and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

The maximum extent of Antarctic sea ice for the year hit a record low, with a reduction of 1 million km2 (an area larger than France and Germany combined) compared to the previous record low, observed at the end of the southern hemisphere winter. Glaciers in North America and Europe also experienced an extreme melt season. Swiss glaciers, for instance, have lost about 10 percent of their remaining volume in just the past two years, as reported by the WMO.

The report highlights the global impact of climate change, providing a snapshot of its socio-economic effects, including its impact on food security and population displacement.

“This year we have seen communities around the world pounded by fires, floods and searing temperatures. Record global heat should send shivers down the spines of world leaders,” said United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres.

In a video message accompanying WMO’s climate report, Guterres urges leaders to commit to urgent action at the UN Climate Change negotiations, COP28. There is still hope, he said.

Greenhouse Gases

“We have the roadmap to limit the rise in global temperature to 1.5 °C and avoid the worst of climate chaos. But we need leaders to fire the starting gun at COP28 on a race to keep the 1.5 degree limit alive: By setting clear expectations for the next round of climate action plans and committing to the partnerships and finance to make them possible; By committing to triple renewables and double energy efficiency; And committing to phase out fossil fuels, with a clear time frame aligned to the 1.5-degree limit,” he said.

In 2022, the observed concentrations of the three primary greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide – reached record high levels. This is the most recent year for which consolidated global values are available. Real-time data from specific locations indicate that the levels of these three greenhouse gases continued to rise in 2023.

Global Temperatures

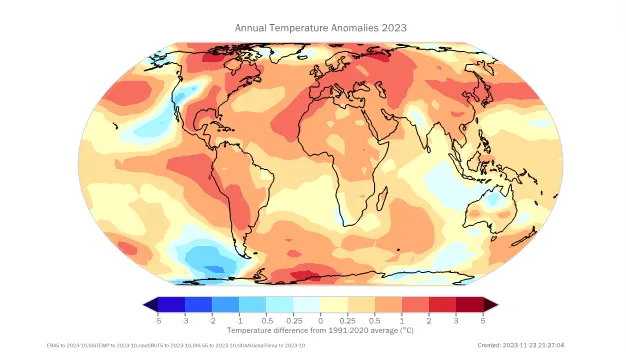

In 2023, up until October, the global average near-surface temperature was approximately 1.40 (± 0.12) °C above the average from 1850–1900. Based on the data up to October, it is almost certain that 2023 will be the warmest year in the 174-year observational record, surpassing the previous joint warmest years, 2016 and 2020, which were 1.29 (± 0.12) °C and 1.27 (±0.13) °C above the 1850–1900 average, respectively.

Record monthly global temperatures were observed for the ocean from April to October, and for the land from July to October.

June, July, August, September, and October 2023 each surpassed the previous record for the respective month by a significant margin in all datasets used by the WMO for the climate report. July, typically the warmest month of the year globally, became the all-time warmest month on record in 2023.

Sea surface temperatures, Sea level rise

Starting from the late Northern Hemisphere spring, global average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) reached a record high for that time of year. From April to September, each month set a new record for warmth, with July, August, and September breaking their respective records by a substantial margin (around 0.21 to 0.27 °C). The eastern North Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and large areas of the Southern Ocean all experienced exceptional warmth, resulting in widespread marine heatwaves.

In 2022, the latest full year for which data is available, ocean heat content reached its highest level in the 65-year observational record.

Warming of the oceans is expected to continue, a change that is irreversible on centennial to millennial timescales. All data sets agree that the rate of ocean warming has shown a particularly strong increase in the past two decades.

In 2023, the global average sea level reached an all-time high since the start of satellite records in 1993. This increase reflects the ongoing warming of the ocean and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets. Interestingly, the rate of global mean sea level rise in the last decade (2013–2022) was more than double the rate observed in the first decade of satellite records (1993–2002).

Extreme weather and climate events

In 2023, all inhabited continents experienced major impacts from extreme weather and climate events, including significant floods, tropical cyclones, extreme heat and drought, and associated wildfires.

Mediterranean Cyclone Daniel caused flooding due to extreme rainfall in Greece, Bulgaria, Türkiye, and Libya, with Libya suffering particularly heavy loss of life in September.

Tropical Cyclone Freddy, one of the world’s longest-lived tropical cyclones, had major impacts on Madagascar, Mozambique, and Malawi in February and March. Tropical Cyclone Mocha, in May, was one of the most intense cyclones ever observed in the Bay of Bengal.

Extreme heat affected many parts of the world, with southern Europe and North Africa experiencing severe and exceptionally persistent heat, especially in the second half of July. Italy reported record-high temperatures at 48.2 °C, while Tunis, Tunisia recorded 49.0 °C, Agadir, Morocco reached 50.4 °C, and Algiers, Algeria experienced 49.2 °C.

Canada’s wildfire season was unprecedented, with the total area burned nationally as of October 15 being 18.5 million hectares, more than six times the 10-year average. The fires also led to severe smoke pollution, particularly in the heavily populated areas of eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. The deadliest single wildfire of the year was in Hawaii, with at least 99 deaths reported – the deadliest wildfire in the USA for more than 100 years.

The Greater Horn of Africa experienced five consecutive seasons of drought, followed by floods, triggering even more displacements. The drought reduced the capacity of the soil to absorb water, which increased flood risk when the Gu rains arrived in April and May.

Long-term drought intensified in many parts of Central America and South America. In northern Argentina and Uruguay, rainfall from January to August was 20 to 50% below average, leading to crop losses and low water storage levels.

Keep Reading

Part 1: Cloudburst in Ganderbal’s Padabal village & unfulfilled promises

India braces for intense 2024 monsoon amid recent deadly weather trends

Support us to keep independent environmental journalism alive in India.

Follow Ground Report on X, Instagram and Facebook for environmental and underreported stories from the margins. Give us feedback on our email id greport2018@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, Join our community on WhatsApp, and Follow our YouTube Channel for video stories.